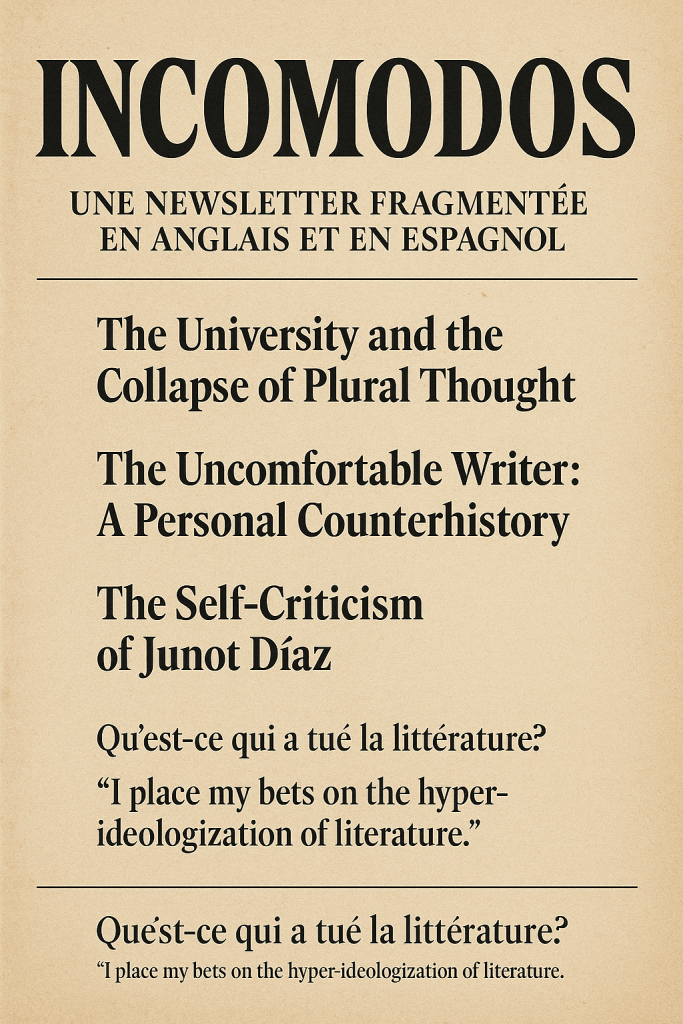

El escritor incómodo: un ejercicio de contrahistoria personal

Israel Centeno

There was once a time when “internationalism” meant solidarity. A romantic word, like something scribbled on onion-skin manifestos, full of promises for universal brotherhood. But the romance didn’t last. From the First International to the Comintern, what began as a project of emancipation often collapsed into centralism, control, and imperial ambition—wrapped in revolutionary rhetoric.

Today, a new kind of Internationale is in place. It doesn’t speak Russian—it speaks English. It doesn’t operate from Moscow—it operates from Cambridge, from Brooklyn, from Palo Alto, from Berlin. Its reach is cultural, not military. Its tone is inclusive, not authoritarian. But its drive is unmistakably imperial. Let’s call it The Pink Internationale.

This new Internationale is powered by hashtags, fellowships, prize circuits, curated festivals, and institutional guilt. It claims to amplify the voices of the Global South—but only those voices that fit a digestible narrative. If your story is too messy, too politically ambivalent, too hard to brand—you’re out. If your trauma doesn’t yield poetic capital, or your rebellion doesn’t flatter the dominant mood board—you’re invisible.

Let’s be clear: this is not about solidarity. It’s about branding. It’s about packaging the periphery for cultural consumption. It’s not help—it’s curation. Authors become tokens. Identity becomes staging. And any deviation from the script is treated with suspicion. You can be radical, sure—but in the correct direction.

Literature becomes a ceremony of belonging. You are expected to say the right things, cite the right thinkers, nod at the right dogmas. Meanwhile, the very institutions that once condemned colonialism now decide—without irony—who gets to “represent” whom. A new imperialism, now with DEI statements, a smiling face, and a pastel logo.

And what about those who don’t fit? Writers who don’t write from guilt. Who critique both empire and revolution. Who refuse to romanticize poverty or weaponize identity. They become outliers. Or worse: problematic. The system doesn’t know what to do with them—so it erases them. Not with censorship, but with silence.

Coming next: the publishers who promise to “give voice,” but only if that voice harmonizes with the choir. Because in the Pink Internationale, freedom of speech exists—so long as it doesn’t disrupt pink.

Writers like Roberto Bolaño, Heberto Padilla, and José Revueltas knew—each in his own historical and stylistic register—that the cost of writing truthfully was not symbolic. It was exile. Silence. Imprisonment. Or worse: absorption by the system they sought to confront.

Bolaño, in The Savage Detectives and Between Parentheses, warned of the cooptation of rebellion, of how poetry could become an aestheticized cemetery. Padilla lived the terror of the “confession,” where literature was no longer art but proof of ideological fidelity. And Revueltas, writing from Lecumberri prison, saw firsthand the violence of institutions—state and literary—when faced with the unforgivable freedom of a writer who won’t play the role.

In today’s world, you won’t be jailed for thinking wrong—but you may be disinvited. You won’t be silenced by decree—but by algorithmic omission. That is the new form of literary discipline. Softer, yes. But just as effective.

The University and the Collapse of Plural Thought

The university, in its highest conception, was meant to be a space where all currents of thought could be studied freely—where no idea was repressed or reduced to a suspect category. A place where doubt had the same right of asylum as certainty, and where thought didn’t require an ideological visa to circulate.

But that model is quietly being replaced by another: the campus as a space of symbolic correction, where certain ideas are tolerated the way one tolerates a disruptive guest—cordially, briefly, and with clear boundaries. In place of pluralism, we find discourse management. In place of debate, ritual affirmation of pre-approved theses. Students are taught not how to think freely, but how to recognize and recite the acceptable script. Adherence is celebrated more than dissent.

This phenomenon is not confined to one country or culture. In the United States, for instance, the case of professor Kathleen Stock at the University of Sussex illustrates how expressing views that challenge dominant ideologies can lead to academic and personal isolation. Stock, who questioned certain aspects of gender theory, faced such pressure and protest that she was ultimately forced to resign.

In another case, historian Michael Phillips was dismissed from Collin College in Texas after publicly expressing opinions on Confederate monuments and public health policy. Phillips argued that his termination was a direct retaliation for his political views—raising urgent questions about academic freedom in American institutions.r

And at Harvard University, an essay by Palestinian scholar Rabea Eghbariah was accepted and then withdrawn from the Harvard Law Review, reportedly due to internal and external pressures. The piece concerned the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a subject that remains taboo even in academic environments that claim to champion open inquiry.

These cases reveal a troubling trend: the university, once a stronghold for freedom of thought and speech, is increasingly shaped by ideological forces that narrow the spectrum of legitimate discourse. The result is a subtle but powerful erosion of academic independence.

It is critical to remember that the true essence of the university lies in its ability to host a multiplicity of voices and perspectives. Only by fostering an environment where all ideas can be discussed and critically examined—without fear of reprisal—can we preserve the integrity and foundational mission of higher education.

Siempre me quedó la duda, y me quedará: ¿qué habría pasado si, en vez de llegar a Estados Unidos huyendo —sí, huyendo— de un régimen autoritario disfrazado de redención popular, yo hubiese venido como uno de sus simpatizantes?

¿Qué habría sido de mí si mi narrativa hubiera estado en línea con la del antiimperialismo cultural que tanto gusta en ciertos circuitos universitarios y editoriales de izquierda en este país? ¿Si, en vez de resistirme al culto al comandante, lo hubiese transformado en materia poética? ¿Si mi exilio no hubiese sido un acto ético, sino una estrategia estilística?

Vine en 2010. Chávez aún era un fetiche progresista. Aquí, en ciertas mesas y fundaciones, se lo defendía como quien defiende a un artista incomprendido. La izquierda norteamericana, o al menos su clase ilustrada, no había aún metabolizado los horrores del chavismo. A excepción de espacios como City of Asylum, en Pittsburgh, donde encontré resguardo sin condiciones ideológicas, todo lo demás parecía estar teñido por una simpatía ambigua hacia ese experimento tropical. Un experimento que ya entonces estaba arrasando con instituciones, con vidas, con la verdad.

Nunca me fui del todo del margen. Ni en Venezuela ni en Estados Unidos. Y eso, en literatura, tiene un precio. En España, por ejemplo, fui acogido por una editorial con entusiasmo, pero luego… silencio. ¿Intrigas personales? Tal vez. Pero sería ingenuo no ver el mapa: el ascenso de Podemos, los vínculos culturales con el chavismo, el subsidio del PSOE a editoriales que abrazaban con fervor la “marea rosa” latinoamericana. Es difícil pensar que todo fue casualidad. Fui incómodo para mi editor, y lo sigo siendo para un sistema que prefiere escritores alineados a causas, no a verdades.

En Estados Unidos, el mercado editorial es otra cosa: más vasto, más encriptado, más impermeable. Si no pasas por Iowa, si no eres parte del circuito académico, si no aprendes el discurso aceptado —el antiamericanismo performativo, el rechazo ritual al imperio, incluso desde dentro del imperio— quedas fuera del juego. Y yo no aprendí ese idioma. No lo hablo. Nunca quise.

Y si, además de simpatizar con Chávez, hubiese hablado mal —y con fervor performático— de Álvaro Uribe en cada entrevista, si hubiese hecho de mi obra un alegato contra las “castas” latinoamericanas —con C mayúscula y rabia curada en clase de teoría poscolonial—, quizás mi recepción habría sido distinta. No importa cuán matizado sea tu pensamiento: si no dices lo que esperan oír, te leen con desconfianza.

No estoy diciendo que no haya sido crítico. Pero mi crítica no fue de esas que se entregan como discursos de investidura. No hubo pronunciamientos oportunos ni hashtag indignados. Mi escritura no encajaba en el molde de lo políticamente correcto que ciertas instituciones estadounidenses —y sus homólogas hispanoamericanas— esperan del escritor “latino”. No me ofrecí como víctima dócil. No abracé el romanticismo narco, ni endulcé la barbarie con corridos literarios. No hice poesía de la violencia para decorar vitrinas de librerías universitarias.

Tampoco milité en el nuevo puritanismo. No construí una voz masculina fingidamente culpable, ni una virilidad arrepentida que pidiera perdón de antemano por haber nacido hombre en América Latina. No escribí desde el mandato de la corrección ideológica ni desde la agenda de redención posmoderna. No me inventé un feminismo de ocasión para agradar a lectoras entrenadas en detectar la sensibilidad aliada. Preferí el riesgo: el de escribir desde donde me dolía, no desde donde convenía.

En una de las pocas veces que fui invitado a leer en una universidad estadounidense, se me acercó un profesor —blanco, con gafas redondas, camisa de cuadros, la culpa bien planchada— y me pidió perdón. No por algo concreto. No por él. Por “el daño que le habíamos hecho a tu país”, dijo, con una gravedad de misa laica.

Yo lo miré con la incomodidad de quien no está acostumbrado a las genuflexiones morales.

“No tienen por qué disculparse”, le dije. “Ni usted, ni los americanos en general.”

Él me miró sorprendido, como si acabara de invalidar una ceremonia.

“Gracias a los americanos,” continué, “Venezuela desarrolló una industria petrolera. Altamente calificada. Moderna. Profesional. Con ella, y a pesar de todos los errores, Venezuela entró en el siglo XX. Con esa industria se construyó infraestructura, se formaron ingenieros, se erigieron ciudades, se diseñó una clase media.”

“¿Y sabe cuándo empezó nuestra tragedia?”, le pregunté. “Cuando se decidió desmantelar todo eso. Cuando nos convencieron de que esa herencia era pecado. Cuando nos dijeron que era mejor volver al siglo XIX en nombre del pueblo, de la identidad, del petróleo nuestro y de la revolución redentora.”

No hubo respuesta. Solo silencio. El tipo que necesitaba sentirse redentor se había topado con una víctima que no aceptaba su misa.

Y quizá eso explique por qué nunca se me invitó, ni siquiera, a enseñar a decir “ba-ba-ba, pe-a-pa-pa”. El abecedario que otros pronunciaban con seguridad se me negó incluso como posibilidad didáctica. Yo, con libros publicados, con experiencia de vida, con lecturas cruzadas entre dos mundos, no era apto para enseñar ni lo más básico. Porque no pasé por los seminarios adecuados, porque no tenía el perfil discursivo exigido, porque no podía sentarme en todos los paneles de género ni en las mesas donde se reparte el derecho de hablar en nombre de lo latinoamericano.

Ni siquiera el conocimiento cultural —ese que se construye no con teoría sino con cicatrices— tenía lugar. Yo no era un traductor del dolor al lenguaje académico. No era útil. No era domesticable.

Y por eso me convertí en lo que nunca buscaron: una voz que no pide permiso ni acta de autenticidad para hablar.

Escribo desde el margen del margen. En inglés con acento. En español con vértigo. Y aún no sé si eso es una derrota… o el único lugar desde donde vale la pena escribir.

What Killed Literature?

Was it hyper-ideologization or new technological platforms?

I place my bet on hyper-ideologization.

Because technology, after all, is just a tool.

But ideology, poorly digested and turned into dogma, is a knife disguised as a compass.

Literature can adapt to digital formats.

What it cannot survive is being required to obey

Heberto Padilla, Fuera del juego (1968) Roberto Bolaño, Between Parentheses (2011, essays) José Revueltas, El apando (1969) Junot Díaz, The Silence: The Legacy of Childhood Trauma, The New Yorker (April 2018) Daphne Patai & Noretta Koertge, Professing Feminism: Education and Indoctrination in Women’s Studies Stanley Fish, Save the World on Your Own Time Lorna Scott Fox, Heberto Padilla and the Cuban Dilemma (The London Review of Books, 1981) Carlos Granés, El puño invisible: Arte, revolución y un siglo de cambios culturales Lionel Trilling, The Liberal Imagination Wendy Brown, In the Ruins of Neoliberalism.

Suggested Readings / Bibliography

Heberto Padilla, Fuera del juego (1968) Roberto Bolaño, Between Parentheses (2011, essays) José Revueltas, El apando (1969) Junot Díaz, The Silence: The Legacy of Childhood Trauma, The New Yorker (April 2018) Daphne Patai & Noretta Koertge, Professing Feminism: Education and Indoctrination in Women’s Studies Stanley Fish, Save the World on Your Own Time Lorna Scott Fox, Heberto Padilla and the Cuban Dilemma (The London Review of Books, 1981) Carlos Granés, El puño invisible: Arte, revolución y un siglo de cambios culturales Lionel Trilling, The Liberal Imagination Wendy Brown, In the Ruins of Neoliberalism

Leave a comment