Literary Voices Under Stalinist Terror

Israel Centeno

“In Stalin’s Russia, literature was a crime and memory an act of defiance. This essay from The Tower of Alexandria revisits the lives of Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Nadezhda Mandelstam—voices that resisted totalitarian silence with whispered poems, burned manuscripts, and unwavering loyalty to truth. A meditation on fear, courage, and the power of the written word to outlive tyranny.”

Israel Centeno

In Stalin’s Russia, totalitarianism seeped into even the most intimate corners of a writer’s life, turning every whispered poem into a potentially subversive act and every silence into a form of involuntary complicity. In May 1934, in the early hours of the morning in Moscow, a sharp knock at the door marked the end of one life and the beginning of another for the Mandelstam couple. That night, the poet Osip Mandelstam was arrested by the secret police after daring to compose a short satirical poem about Stalin. With that act, a chain of terror was set in motion—one that would eventually ensnare other authors like Mikhail Bulgakov and Anna Akhmatova, each of whom, in their own way, endured surveillance, censorship, and ostracism under the Stalinist regime. Yet, from that same terror, strategies of resistance were also born: memory, oral transmission, and the stubborn will to keep writing for posterity. This essay, part of the Lighthouse of Alexandria series, explores the intertwined stories of Mandelstam, Bulgakov, and Akhmatova—as well as the crucial role of Nadezhda Mandelstam, Osip’s widow and guardian of his memory—to reflect on how totalitarianism attempted to silence literary voices, and how those voices responded with fear, self-censorship, and an unyielding fidelity to the word.

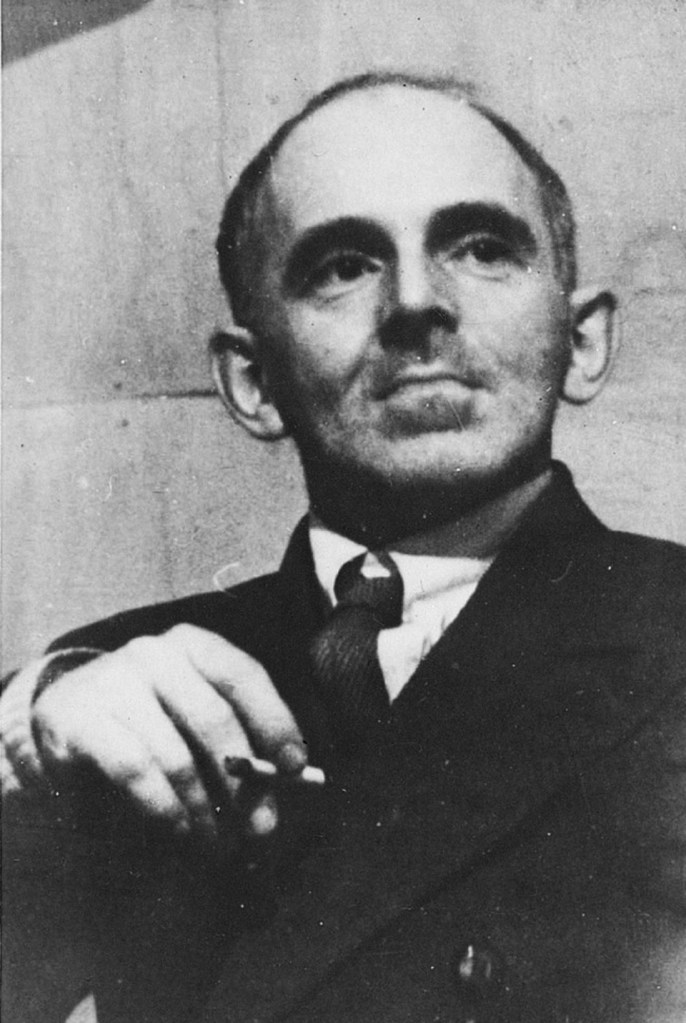

Osip Mandelstam: The Fatal Epigram and Poetry as a Crime

Photograph of Osip Mandelstam in the 1930s. He was arrested in 1934 for quietly reciting a satirical poem about Stalin, a reflection of the era’s pervasive climate of terror.

Osip Mandelstam, one of the leading figures of Russian Acmeist poetry, committed the “crime” of writing an epigram against Stalin in 1933. The poem—known as The Kremlin Highlander, or simply The Epigram to Stalin—bitingly captured the atmosphere of suffocating paranoia that gripped the country, including daring images of the dictator: “His thick fingers are fat as worms…”, “Each death for him is a delight,” and so on. Mandelstam knew he had created something fatal: he recited it only to a handful of trusted friends, including Boris Pasternak, Anna Akhmatova, and a supposed admirer who turned out to be a police informant. In the Soviet Union, poetry could amount to a death sentence. “Only in Russia is poetry respected—it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so often a motive for murder?” Mandelstam reportedly said shortly before his arrest.

Those satirical lines—which mocked Stalin’s absolute power—somehow reached the ears of the secret police through still-unidentified channels. The head of the NKVD himself, Genrikh Yagoda, took personal interest in the matter: it was one of the first cases he handled after assuming the position. According to Nadezhda Mandelstam, he even memorized the poem and recited it fluently (with a macabre aesthetic appreciation) before signing the arrest order. On the night of May 13–14, 1934, agents burst into the Mandelstams’ home searching for “something very specific”—the poem—but they found no written trace, as Mandelstam had never committed it to paper: it existed only in the memory of its creator and those who had heard it. Still, one of those listeners rushed to dictate it to the police, sealing the poet’s fate.

Osip was arrested and sent into internal exile, first to Cherdyn and later to Voronezh, narrowly escaping execution thanks to the intercession of influential friends like Nikolai Bukharin and Pasternak. But the “countdown to the inevitable” had begun: in 1938, Mandelstam was arrested again and sentenced to five years of forced labor, dying later that year in a transit camp near Vladivostok.

The Mandelstam case is a perfect illustration of how Stalinist totalitarianism lashed out at the innermost realm of the writer. His brief private poem unleashed a storm of repression not only against him but also against those close to him: the Soviet regime, feeling mocked by a few verses, responded with broadened terror. The Epigram to Stalin played a role not only in Osip’s arrest but also in the temporary marginalization of Anna Akhmatova herself, and in the arrests of her son Lev Gumilyov and her partner Nikolai Punin.

The surveillance network extended its reach, casting suspicion over the entire literary community. “Collaborators infiltrated freely: every family scrutinized its acquaintances, searching for provocateurs, informers, and traitors,” wrote Nadezhda Mandelstam. The regime thereby sowed universal distrust: “Nothing binds people more tightly than complicity in the same crime,” she remarked regarding the Cheka-NKVD’s tactics, noting how the constant threat of being “summoned” by the police broke social bonds and confined each person to a fearful silence.

When a poet dared point out the nakedness of the tyrant, there was no chorus to back him up; on the contrary—paraphrasing a familiar tale—there was no innocent child to cry out that the Emperor had no clothes. In Stalin’s Russia, “when a poet dared to criticize the Great Leader… fear and terror seized everything.” The price of poetic truth was solitude and isolation.

Nadezhda Mandelstam: Memory Against All Hope

The tragedy of Osip Mandelstam cannot be understood without his wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam, who became the custodian of his legacy and one of the most penetrating chroniclers of Stalinist terror. After Osip’s death in the Gulag, Nadezhda took on the mission of preserving his poems and his memory during a time when merely possessing verses could lead to ruin. With the help of a few loyal friends, she managed to save her husband’s work largely thanks to her prodigious memory. She knew that if she wrote down Osip’s unpublished poems, they could be discovered during a home search; so she chose the path of oral transmission: she would memorize the verses by heart and then burn the manuscripts.

“To avoid Stalin’s persecution, the poet Anna Akhmatova burned her writings,” notes critic Martin Puchner, “and taught the words of her poem Requiem to a circle of friends from memory. By going ‘pre-Gutenberg,’ she ensured its survival.” Nadezhda Mandelstam applied that same pre-Gutenberg principle to Osip’s verses: entrusting them solely to the fragile yet resilient page of the human mind. Her memory, and that of her co-conspirators, became “the paper on which Akhmatova [in her case] preserved and revised her poem word by word, comma by comma”; in Nadezhda’s case, this method saved dozens of Osip’s poems that would otherwise have been lost in the bonfire of time.

By the late 1950s, partially rehabilitated after Stalin’s death, Nadezhda began to set her memories down in prose, giving shape to Hope Against Hope (1970). The book, written in “elegant, measured, and exact prose,” is at once an enduring love song to Osip and a painful indictment of tyranny. With luminous clarity, Nadezhda recounts the tragic experiences of her husband and his generation, without a trace of self-pity, composing what one critic called “a monument to human dignity in the worst of times.”

In its pages, she confesses that fear became the dominant emotion of those years: “Akhmatova and I once admitted to each other that the strongest feeling we had ever known—stronger than love, jealousy, or any other human emotion—was terror and what it brings with it: the horrible and shameful sense of total impotence.” Yet she draws a distinction between shameful fear (which preserves a person’s humanity) and servile fear: “As long as fear is accompanied by a sense of shame, one remains human and not a cringing slave… It is that sense of shame that gives fear its healing power and offers the hope of regaining one’s inner freedom.” This reflection, shared in intimate conversation between two surviving poets, shows how even terror could carry a moral lesson: the shame of being afraid reminded them that they should not surrender entirely to the regime.

In Hope Against Hope, Nadezhda lays bare the mechanisms of Soviet repression. She reveals, for example, how the secret police summoned countless citizens without any clear reason, simply to entangle them and sow distrust: “They summoned people who were afraid of losing their jobs, people who wanted to advance, people who wanted nothing and feared nothing, and people willing to do anything… It wasn’t about gathering information. Nothing binds people more than complicity in the same crime: the more people could be implicated and compromised, the more traitors, informants, and spies there were, the greater the number of people supporting the regime and wishing it would last a thousand years. And when everyone knows that everyone is being ‘summoned’ like this, people lose their social instincts, the ties between them weaken, everyone retreats into their corner and shuts their mouth—which is an invaluable benefit for the authorities.”

This passage, chilling in its clarity, captures the deliberate social atomization that Stalinism sought: to turn each individual into an isolated, silenced being, fearful and perhaps guilty of something, so that no one would dare raise their voice. In contrast, the very existence of Nadezhda’s book is an act of recovered voice: “I decided it was better to scream. Silence is the true crime against humanity,” she wrote. And scream she did—with her pen. Her testimony not only documents horrors; it is itself an act of resistance through memory and the written word.

Thanks to her, we know, for example, that Yagoda—the ruthless head of the NKVD—could recite Mandelstam’s poem from memory but would not have hesitated to “destroy all literature, past, present, and future, if he thought it served his interests… To people like him, human blood is like water.” Phrases like this, charged with irony, pain, and contempt, make Hope Against Hope a unique work, marked by “sobriety, lucidity, beauty, and transparency” in its denunciation of terror. In the end, Nadezhda achieved her purpose: she saved Osip’s poetry from oblivion and left the world with one of the most harrowing testimonies of the human condition under totalitarianism.

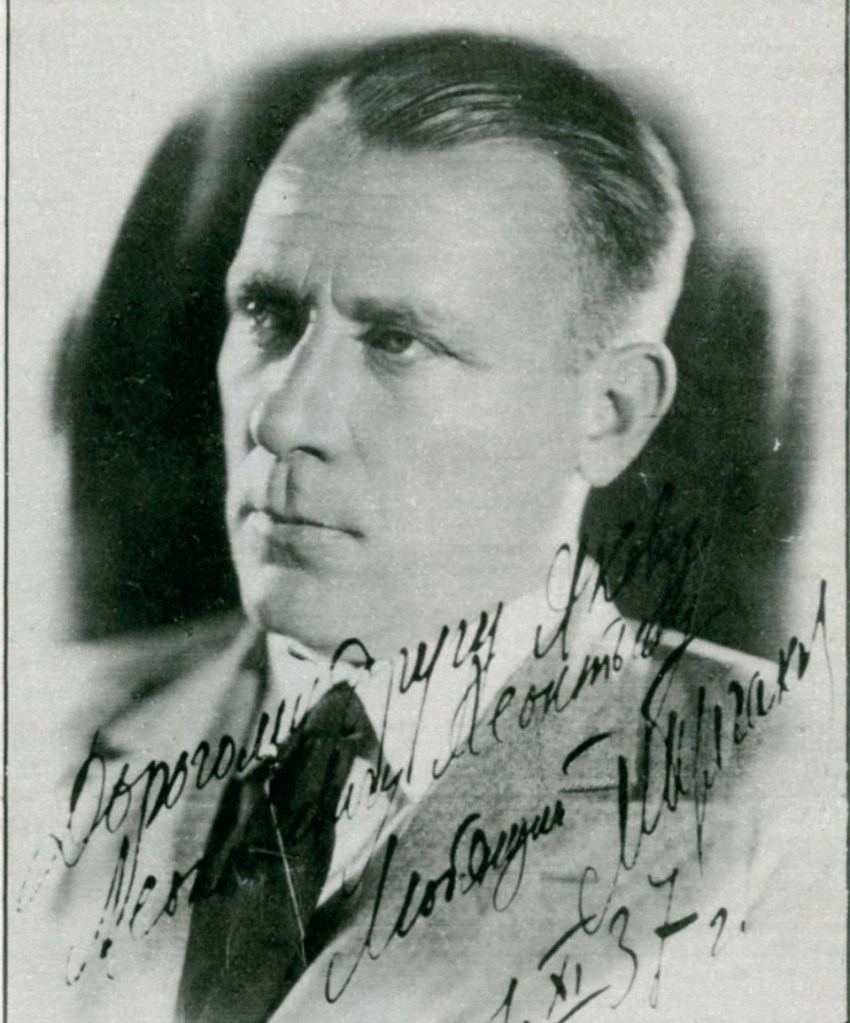

Mikhail Bulgakov: The Master and the Arbiter (Stalin’s Ambiguous Protection)

Portrait of Mikhail Bulgakov signed by the author himself in 1937. Though Stalin admired his theatrical talent, the novelist endured years of censorship and surveillance; his masterpiece The Master and Margarita would only see the light decades after his death.

While the Mandelstams faced open persecution, Mikhail Bulgakov experienced a different but equally revealing fate under Stalinism: a disconcerting blend of favor, censorship, and personalized surveillance by the dictator himself. A playwright and novelist, Bulgakov was the author of biting satires of Soviet life (Heart of a Dog, The Novel of Mr. Molland, etc.), which made him a figure of suspicion. By 1930, frustrated that his plays were consistently banned or trashed by official critics, he wrote a desperate letter to Stalin and other high-ranking officials. In it, he declared that he had spent “ten years cornered, unable to publish or stage my works… [therefore] I appeal to you to intervene and authorize my expulsion from the USSR together with my wife.”

It was a bold and sincere gesture: Bulgakov confessed that he could never write according to ideological dictates and would rather live in exile than censor himself. Surprisingly, Stalin did not respond with arrest—but with a personal phone call. The famous conversation took place on April 18, 1930: Stalin asked if Mikhail really wanted to leave. Caught off guard and in reverent panic, Bulgakov quickly retracted his request for exile, mumbling that a true writer could not work far from his homeland. Stalin then offered him a peculiar reprieve: he secured him a position as assistant director at the Moscow Art Theatre, allowing him to remain in the Soviet Union, but without granting him true freedom. Bulgakov “stayed in the Soviet Union. He remained dry-docked. He remained full of frustration.” That permission to live came with the taste of captivity: “he was never allowed to live in peace or to publish his novels freely,” as one commentator summarized.

Indeed, Bulgakov continued to suffer relentless censorship. Stalin, in a display of ambiguity, was an admirer of some of Bulgakov’s work—it’s known that he attended The Days of the Turbins, a play based on one of Bulgakov’s novels, more than a dozen times—and he intervened several times to protect him from total ruin. Thanks to this strange patronage, Bulgakov was never arrested or sent to the Gulag—an exceptional fate among “problematic” writers of the time. But the protection had firm limits: his most critical works were banned or shelved indefinitely. The state granted him life in exchange for public silence.

This push and pull became evident in a specific episode: in 1939, Bulgakov tried to win favor by writing a laudatory play about Stalin’s youth (Batum) for the dictator’s birthday. The result? Stalin also banned that play, without explanation. It was as if the dictator enjoyed playing cat-and-mouse with the writer: allowing him to survive, but never to speak freely. Paradoxically, this situation drove Bulgakov to channel all his daring into a work meant “for the drawer.” Convinced that his great novel would never be published in his lifetime, he decided to make it as subversive and brilliant as he pleased.

The result was The Master and Margarita, written in secret during the second half of the 1930s. In this fantastical and satirical novel, the Devil (Woland) visits Moscow accompanied by a bizarre entourage—including a giant black cat—and exposes the hypocrisy of Soviet society. The novel contains, among many layers of meaning, a scathing allegory of power and culture under Stalinism: there are sycophantic literati, corrupt bureaucrats, and a pervasive climate of absurdity and fear, thinly masked by dark humor. Bulgakov poured his personal experience into the character of “the Master,” a misunderstood novelist whose work is censored and who ultimately burns his manuscript in a fit of despair.

That image reflects a real incident: in 1930, fearing reprisals, Bulgakov partially burned the drafts of a novel about Pontius Pilate, an early version of what would become The Master and Margarita, shortly before sending his plea to Stalin. Years later, in the novel, the Devil Woland corrects the Master when he laments destroying his work: “You don’t believe, but manuscripts don’t burn.” That phrase—“manuscripts don’t burn”—has since become legendary, for it encapsulates a profound truth: the indestructible permanence of literary creation in the face of censorship.

Indeed, Bulgakov had to rewrite his novel entirely, driven by the conviction that ideas would survive. And time proved him right. Though The Master and Margarita remained unpublished during his life (Bulgakov died in 1940, worn down by illness and frustration), the manuscript did not vanish into oblivion: it circulated in underground copies (samizdat) and was finally published in 1966 during a brief thaw, with the full version appearing in 1973. By then, the novel had become a phenomenon: eager readers hand-copied chapters, scrawled graffiti on the apartment building where the story takes place (and where Bulgakov had lived), and whispered its lines as if reciting scripture. Woland’s prophecy was fulfilled.

Bulgakov’s story shows how the relationship between creator and tyrant could be cruelly complex. Stalin played a dual role: patron and censor. He offered “rewards” (a job, limited protection) while simultaneously stifling him with prohibition. One analyst described it this way: “The dictator took a personal interest in the author, like a sociopathic child with a pet he alternately praises and tortures.” Stalin could praise Bulgakov’s talent and still censor him mercilessly. Thanks to this capricious interest, Bulgakov was “suspect until the end of his days” but escaped the physical purges.

He died of natural causes—though prematurely—but with the bitter awareness that his best works were condemned to silence. In his last ten years, supported by his devoted wife Yelena, Bulgakov dedicated himself to the impossible task of completing his masterpiece. Those were his “dark years, of lethargy and ulcers,” as he allegorized them in the novel, in which he persevered by writing “for the void,” knowing that no Soviet editor would dare publish him. And yet, in that seemingly absurd act of literary faith lay his posthumous victory. “Manuscripts don’t burn”: true literature finds a way to elude its inquisitors—if not in the present, then in the future.

Indeed, the influence of The Master and Margarita on later Russian culture was immense, becoming a symbol of creative freedom against tyranny. Many Soviet writers of later generations took Bulgakov’s phrase as a motto for continuing to write “for the drawer,” in the hope of a future reader. In the novel itself, when Woland retrieves the burned manuscript and returns it to the Master, he affirms the supremacy of imagination over violence: not even the Devil believes it possible to entirely destroy a work of the spirit.

Anna Akhmatova: The Poet of Hidden Memory

If Bulgakov resisted by hiding his novel in a drawer, Anna Akhmatova resisted by hiding her poems in living memory. Akhmatova, one of Russia’s most important poetic voices, endured the regime’s violence firsthand: her first husband, the poet Nikolai Gumilyov, was executed in 1921, falsely accused of plotting against the Bolsheviks. Years later, her son Lev Gumilyov would be arrested in 1938 at the height of the Great Terror, and again after the war, serving long sentences in the gulags. Her friend and third husband, the historian Nikolai Punin, also died in a camp in 1953. Akhmatova thus suffered the loss of her family at the hands of the totalitarian state, while she herself remained under constant suspicion.

From 1925 to 1940, she was nearly silenced: forbidden to publish, her poetry dismissed as “harmful” or “reactionary” for not conforming to socialist realism. Yet Akhmatova never stopped writing. Like Nadezhda Mandelstam, she understood that paper was no longer a safe place for poetry. When her son Lev was arrested in 1938, she burned all her notebooks of poems for fear they would be used as evidence against her. From then on, she resolved to memorize everything she composed: each new poem was learned by heart and then destroyed on paper, recited only in whispers to intimate and trustworthy friends.

This was a deliberate shift from written literature to oral tradition, forced by circumstances. Her poetry became more fragmented and encrypted, designed to be remembered and passed on by word of mouth rather than printed. This method ensured that if the police raided her home, they would find no “evidence”—but it placed on Akhmatova and her circle the sacred burden of memory.

Akhmatova’s crowning work of this period is the poetic cycle Requiem (1935–1940), a harrowing lyrical monument to the victims of Stalin’s terror. Requiem was born from her personal experience of standing in line for seventeen months outside the infamous Kresty Prison in Leningrad, trying to learn news of her imprisoned son. In the famous anecdote that opens the poem, a woman in the queue, shivering from cold and with a gaunt face, recognized or intuited who she was and whispered to her, “Can you describe this?” Akhmatova answered: “I can.”

That brief reply held her entire vocation: to be the voice of those who could not speak, to bear poetic witness to shared anguish. Requiem, composed piece by piece, mourns the execution of Gumilyov, the arrest of Punin, Lev’s imprisonment, and at the same time becomes a “hymn of resistance by the people against Stalin’s power.” Naturally, a poem like this could never be published under Stalin. Akhmatova kept it secret for decades. She would write lines to refine them, recite them to her closest friends (such as Lydia Chukovskaya), and then burn the paper in the ashtray. Each friend memorized a section.

“She taught [the poem] to her closest friends so they could remember it after her death… state terror had forced people to live as if the printing press had never been invented,” writes Martin Puchner of this situation, so similar to Nadezhda’s. For years, Requiem existed only in the minds of Akhmatova and her trusted circle, surviving the test of a “second memory”: her verses endured, sheltered in the soul, immune to police searches. It was not until 1963 that Requiem was published (in Russian, in Munich); and not until 1987, during perestroika, that it was printed in the Soviet Union.

In the meantime, Akhmatova witnessed the destruction of the cultural world she belonged to. “Akhmatova survived Stalin’s terror and the persecution of her fellow Silver Age writers: Mandelstam died en route to the Gulag, Tsvetaeva hanged herself, and Pasternak was hounded to his death,” one article summarizes. She herself was attacked: in 1946, the regime—through Andrei Zhdanov—publicly denounced her, expelled her from the Union of Soviet Writers, and called her a “nun and whore,” claiming her art was alien to the people. But none of this silenced her inner voice.

Akhmatova believed that “her transparent verses could preserve memory and save it from a second death: oblivion.” This conviction sustained her. She knew she could not save the victims of the purges, nor her own son from his ordeal, but she could save the truth of what had happened through her poems. Indeed, Requiem and other poems from her testimonial cycle were guarded like a secret treasure until a gentler time allowed them to be shared with the world.

By the 1960s, Akhmatova herself had become a kind of living symbol of cultural resistance: she regained a degree of prominence as an “unofficial leader of the dissident movement” and was revered both in the Soviet Union and abroad. A sign of her moral triumph is that, before her death in 1966, she lived to see many of her early poems published and received public tributes long denied to her.

But perhaps her deepest victory lies in those lines from Requiem where she speaks not only for herself but for all women who endured the torture of uncertainty:

“Beside this grief, all others fade;

we bear the yoke of sorrow, eyes downcast.

Something has nailed us to the scaffold…”

Akhmatova ensured that such sorrow would not be in vain: her poetry etched that anguish into history, preventing it from vanishing. By memorizing verses instead of writing them down, she found a crack through which truth could escape censorship.

Literature, Fear, and Survival

The stories of Osip Mandelstam, Nadezhda Mandelstam, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Anna Akhmatova converge at an essential point: the power of the word versus the power of bayonets. Each of them, in varying degrees, endured the Stalinist regime’s determination to control not only public expression but even private thoughts and the manuscripts kept in desk drawers. Stalinist totalitarianism seeped into the writer’s most intimate spaces: hidden microphones, friends turned informants, censors embedded in conscience, leading to self-censorship. The result was a climate of internalized terror that forced tragic decisions: to burn one’s own book in order to survive? To remain silent in order to protect one’s child?

Akhmatova described how, under that ubiquitous terror, the entire population seemed to live in a trance, paralyzed by fear. And yet, from that frozen silence also arose sublime acts of defiance. When speaking could be lethal, total silence became the true crime, as Nadezhda Mandelstam concluded. That’s why she chose to “scream” by writing her memoirs; Akhmatova chose to “speak” in a whisper, memorizing her poems; Bulgakov chose to “outwit” the oppressor by locking the truth into a fantastic novel meant for a future time.

These choices came at great personal cost: they lived haunted by fear, feeling “bound hand and foot, with a horrible and shameful sense of impotence.” But that shame at feeling powerless, as Nadezhda put it, was the very thing that saved their humanity—because it reminded them that they could still resist from within. Resistance sometimes meant refusing to yield in the smallest of ways: remembering a poem, copying a banned manuscript, hiding verses in one’s memory. These seemingly modest acts were formidable antidotes to the total oblivion the regime sought to impose.

It was, in the words of a Spanish critic referring to Hope Against Hope, “the indestructible power of poetry—and by extension, culture—crashing against the most sophisticated repressive apparatus.” In the end, poetry and literature outlived Stalin. Mandelstam, once a proscribed name, is now celebrated as one of Russia’s greatest poets; Akhmatova is read across the globe; Bulgakov has become synonymous with liberating satire against tyranny; and Nadezhda Mandelstam’s testimony stands as “one of the literary monuments” to the memory of the twentieth century. Their voices, once hidden in darkness, now shine.

As we close this journey, we return to the symbolic lighthouse of Alexandria that inspires this series: a beacon of culture safeguarding knowledge amid devastation. In the dark night of Stalinism, these writers were lighthouses in their own right, even when forced to hide their light under veils of secrecy. Against the dictator’s dream of a thousand-year reign, they ensured that the intimate truth of their lives and works would outlive fear and reach the future.

“Manuscripts don’t burn”—indeed—and sometimes, neither does hope. Every memorized poem, every hidden page, every whispered line was an act of faith in posterity, a vote of confidence that one day, literature could once again be read aloud without terror. That day came—and with it, our understanding of the enormous courage of those who, in the face of imposed silence, chose not to fall completely silent. Their memoirs, their novels, their verses are the proof that, against the assault of totalitarianism, artistic creation can become refuge and resistance, beacon and legacy.

Yes, the writer’s intimacy was besieged—but not completely conquered: in the inviolable sphere of mind and word, they preserved a final freedom. And thanks to that, we can still hear their voices today, guiding us like lights through the shadows of history.

Leave a comment