Israel Centeno

Reading Journal – Day 1

Pittsburgh, May 16. A long, dense day—the kind where light never really arrives and you feel like the sky weighs more than your body. Early in the morning, we discussed the looming effects of federal budget cuts in a meeting. I called my congressman, senator, vice president, president. I don’t know if it makes any difference. I have the sense—and I’m not alone—that we are living under an administration that has turned all criticism into enemy territory. I left with my spirits lowered and my health shaken. Yesterday, over coffee in Bloomfield, I told an old friend—a self-declared skeptic—that without God, all this would be much harder. I have God, I told him, and that allows me to move forward with a certain lightness, even when my body aches and my medical prognosis is uncertain.

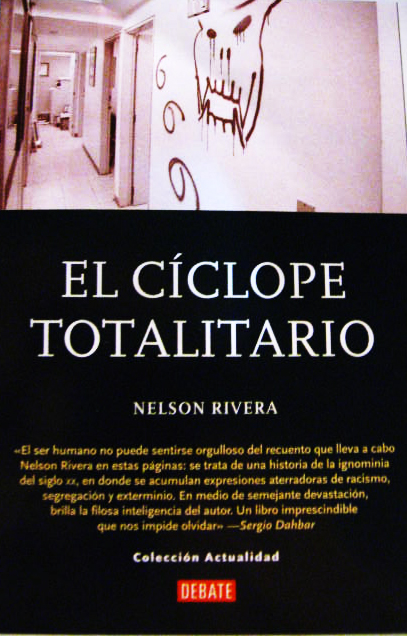

Today I begin reading The Authoritarian Cyclops by Nelson Rivera. I hadn’t read it before, though it was published in 2009, the very year I left Venezuela with no possibility of return. I saw reviews, knew of its existence, but my exile was urgent, chaotic, a rupture—and what I didn’t carry with me remained suspended in an inaccessible time. Only now—fifteen years later, thanks to the generosity of Vasco Szinetar—can I settle that debt. I open it as one opens a book that had long been destined for them, but whose reading had to wait until the storm passed.

As soon as I open it, in the first few pages, I feel at home. Not geographically, but in the gravity. Rivera writes with surgical precision, but also with a strange kind of intellectual compassion. He states at the outset that to think about war in times of peace is almost a contradiction, but also a duty. War, he says, doesn’t erupt like lightning; it gestates in the shadows, in collective psychic denial, in the emotional veto of imagining the unthinkable. And that strikes me deeply. Isn’t that exactly what happened to us Venezuelans? Didn’t we live through a war without war, an annihilation without trenches, a loss of liberties disguised as popular epic?

What Nelson Rivera calls “abstract emotions”—nation, people, homeland, revolution—I experienced as slogans, then rhetorical weapons, then instruments of exclusion. It shakes me to read: “Every war is preceded by a high tide of hope.” What a sentence. What precision to describe that moment when we believed everything would change. And it did, of course. But toward the darker. The “new man” ended up being a cyclops, yes, but not out of vision, but due to the mutilation of thought: a single gaze, a single language, a single truth.

I read from Pittsburgh, from this place that fifteen years ago meant nothing to me and is now the city where I grow old. I’ve become—I once said as a joke—an Appalachian mountaineer, removed from the editorial corridors of my country, a belated observer of its books, a displaced reader. This reading, then, is also a form of return. But not with nostalgia, rather with method.

Rivera’s book demands I pause. I can’t read it as one looks for quotable ideas. It’s a text to ruminate, to dialogue with philosophers, linguists, phonologists, and literary thinkers who have warned of the destructive power of language when it becomes slogan, when it ceases to serve thought and becomes a device of domination. Arendt, Steiner, Michael Ignatieff, even Simone Weil come to mind, as do echoes of our own tradition of critical thought—now so scattered, reduced to ashes or social media posts no one reads.

Nationalism, populism, sentimental socialism, as Rivera rightly points out, are not ideas but emotional devices. They don’t operate on the level of reason but of the viscera. In this sense, the book dialogues with a whole tradition of thought that includes everything from Ernesto Laclau’s discourse theory to Umberto Eco’s semiotics of fascism. Rivera patiently dismantles the way these symbolic apparatuses—when reified and embedded into the community—can produce war as an inevitable emotional logic. He says it without alarmism, with a clarity that chills.

Today I can only read a few pages. I will continue tomorrow. This will be my way of practicing criticism from exile: not as definitive analysis, but as daily dialogue, journal of thought, a way of accompanying a reading that arrives fifteen years late but with an urgency that remains intact.

I invite you to follow these entries, one by one, as if we were conversing together, under this cloudy sky, in a corner of Pittsburgh where there’s still hot coffee, and where—despite everything—not all is lost.

The sky hasn’t changed since yesterday. The light remains absent. And although I tried to put the book down—because of the density of what it says—I couldn’t. I kept reading, like one opening a door that leads not only to the past, but to the raw present: Venezuela in its regression, the world in its silent substitution of liberalism by increasingly sophisticated forms of emotional, symbolic, institutional control.

With the measured pace of a thinker who knows language must not yield to urgency, Nelson Rivera develops a meditation that is not only about war but about the political soul of our time. What he calls “abstract emotions”—that magma of homeland, people, revolution, redemption—has ceased to be the patrimony of classic dictatorships and has become the structural raw material of what we might call the new affective authoritarianism: one that doesn’t need shouts or uniforms to impose obedience.

As I read, I think about how the last fifteen years have not only returned Venezuela to the 19th century but have confirmed that modernity was not irreversible. The fall of the Berlin Wall did not inaugurate the end of history, as Fukuyama believed, but merely a truce. What we are seeing now is a world sliding into soft but relentless forms of governance: the algorithm as judge, the hoax as doctrine, the enemy as structural need.

Rivera puts it this way: war, before it is cannon, is language. A language that “flattens the multiple,” that “levels,” that turns everything into an inescapable system of oppositions: us/them, loyal/traitor, kill/die. In that binary grammar, freedom has no possible conjugation. Only the monotonous echo of the slogan remains. That is where we come in, we who still write, as the last phonologists of dissent.

I read and underline: “the language of war has a purpose: to flatten, reduce, distort reality into insignificance.” I think of how many times that operation has repeated among us. In how many state speeches—of all kinds—that have turned the verb into a club. This warrior tongue, as Rivera explains, does not communicate, it commands. It does not seek meaning, it imputes. It does not interrogate, it dictates. War—he reminds us—does not begin with bombs, but with the slow normalization of that hollow, bombastic language that turns difference into a threat.

What Rivera denounces with rigor—and without shrillness—is not only the machinery of physical horror but also the aestheticization of conflict. In a world saturated with screens, war has become transmissible, editable, digestible. Propaganda no longer needs to tell the truth; it only needs good graphic design. It is the contemporary version of the “control of the narrative” that Walter Benjamin warned of in the 1930s: fascism does not destroy art, it makes it part of the decor of power. Today, that aestheticization becomes algorithm, trending topic, storytelling. The authoritarianism of the present does not impose silence: it imposes noise. So much that dissent is lost in the cacophony. Against that, this book is an act of deprogramming.

Later, Rivera offers testimonies. Not figures or concepts: bodies, wounds, children torn apart, women spat upon by their tormentors, men hiding in swamps with their children. These stories (Armenia, Cambodia, Rwanda, Vietnam) do not belong to one continent or one ideology. They belong to the dark heart of the human being when language has ceased to be a home and become a field of extermination.

It is hard to read these fragments without nausea. But I also realize that one cannot think about today’s politics without going through these pages. Because war no longer needs to be called war. It can be called “beautiful revolution,” “emerging order,” “civilizational project.” It can have spokespeople with microphones, not rifles. But the effects are the same: silence, submission, hunger, fear.

Rivera forces us to face what others elude with functional theories or conciliatory discourse. He reminds us that true barbarism is not that which produces screams, but that which imposes silence. The silence heard in the testimonies of those who survived everything and no longer know how to speak.

There is no metaphor here. There is accuracy. War—he writes—is “the fall of God,” “the dissolution of the contracts of the human.” Reading that in 2024 is to understand that it is not enough to denounce old-fashioned authoritarianism. We must also interrogate the new emotional order that surrounds us: one that turns politics into performance, truth into meme, morality into algorithm. And then ask: will this new model stop here? Will China be its final station or are we approaching a Scandinavian “paradise” where freedom is merely a footnote?

In the end, this reading becomes a testimonial exercise for me. Not only for what Rivera says, but for what it awakens in me as a reader who has seen his country sink without a formal war, but under all its logics. Reading The Authoritarian Cyclops is not just reading about war; it is reading from a wound. A wound that does not bleed but does not close either. This book, in its sobriety, in its drama-free forcefulness, brings me back to the heart of a question almost no one dares to ask in public anymore: What do we do when language has been hijacked by those who use it to justify the unjustifiable? Perhaps, for now, the only answer is to keep reading. And to write, even from the margins.

I keep reading. I cannot stop. Not with a book like this. Not with this gravity. Not with this echo that reminds me, with each line, that to think is to resist. That to narrate is to contradict the slogan. That every word not surrendered is a small fire against the language of war.

More tomorrow.

Leave a comment