Israel Centeno

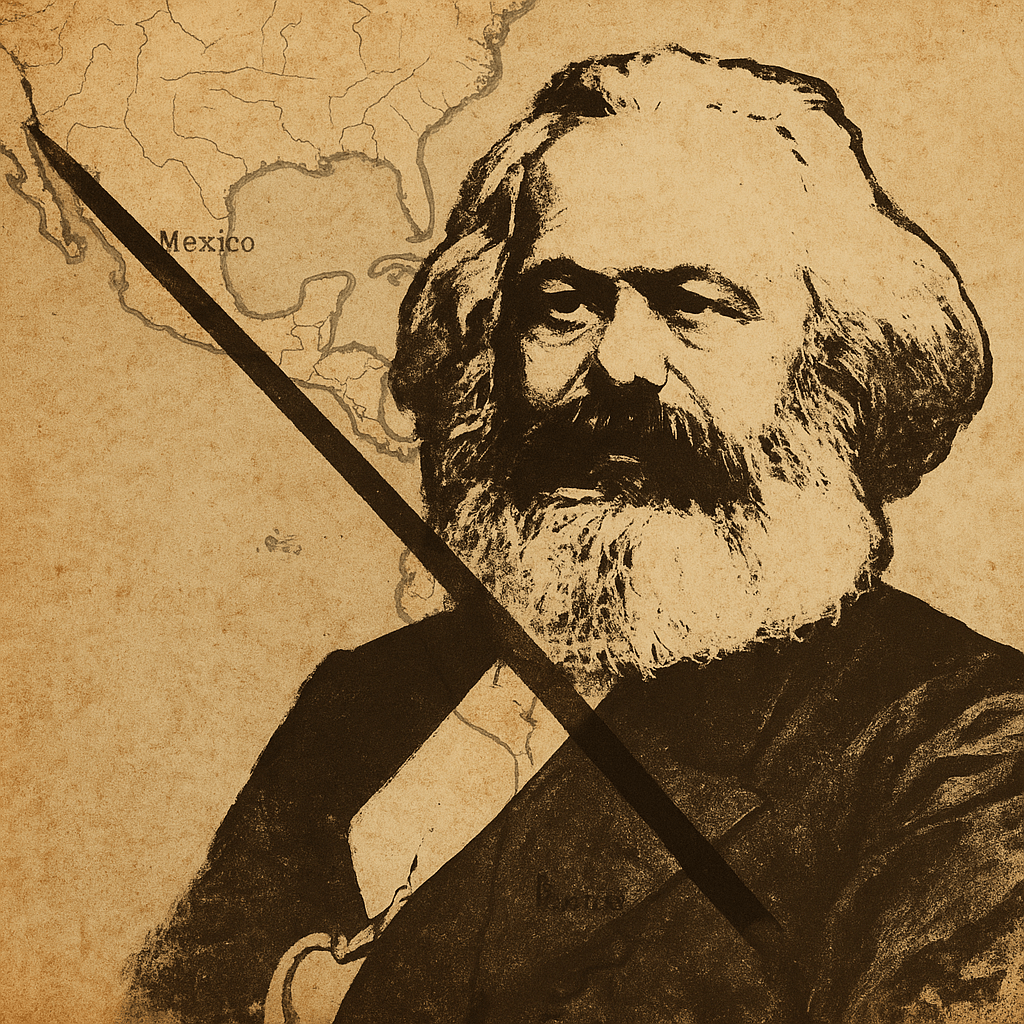

There is a question that should be asked more often, though many avoid it out of convenience or dogma: how can a Mexican, a Venezuelan, or any Latin American still call themselves a Marxist when Karl Marx himself despised their people, ridiculed their culture, and justified their subjugation?

This is not about interpretation. It’s in his own words, plain and brutal. Marx celebrated the U.S. invasion of Mexico, glorified the seizure of California as a “civilizing” act, and described Mexicans as degenerate caricatures of Spaniards. His support for the Yankees was not incidental — he saw them as the torchbearers of Anglo-Saxon progress, the necessary agents of history who would pave the way for the triumph of civilization over barbarism.

In a notorious passage, Marx wrote:

“Is it a misfortune that magnificent California was seized from the lazy Mexicans, who did not know what to do with it? That the energetic Yankees will exploit the mines of California, increase the means of circulation, and, within a few years, populate and develop commerce along the Pacific coast, build cities, open steamship lines, and build a railroad from New York to San Francisco? That for the first time the Pacific Ocean will be really opened to civilization? What does the ‘independence’ of a few Spanish Californians or Texans matter, or the violation of ‘justice’ and other moral principles, compared to such historical facts?”

To Marx, conquest was not an injustice — it was a historical necessity. He saw no value in the sovereignty of “lazy Mexicans,” no legitimacy in the suffering of a people invaded. What mattered was the railroad. What mattered was industry. What mattered was the Anglo-Saxon model of modernity.

And this wasn’t an isolated judgment. Marx held deeply racist views about Hispanic peoples. He wrote that:

“The Spaniards are already degenerate. But now a degenerate Spaniard — a Mexican — is an ideal: all the vices, boasting, bombast, and quixotism of the Spaniards to the third power, but not even a trace of their solidity.”

This wasn’t political analysis. It was a racial insult. It wasn’t critique. It was disdain.

Nor did he spare Simón Bolívar, the liberator of South America. Marx dismissed him as a coward, a fraud, a petty tyrant — simply because Bolívar didn’t fit his rigid model of a “proper” revolution. Marx had no patience for the creole, the mestizo, the hybrid rebel who fought outside the logic of European revolutions. His horizon was limited to London, Paris, Berlin. Everything else — from the Andes to the Caribbean — was peripheral, childish, irrelevant.

Even Marx’s ideas of class struggle were crafted for European realities. His schema of historical stages — feudalism, capitalism, socialism — is a linear myth that never truly applied to Latin America, Africa, or Asia. It was a fantasy dressed as science, a theology of progress built on industrial smokestacks and German philosophy.

Marx did not just fail to understand Latin America. He denied its value. His thought was shaped entirely by Eurocentric ideals: civilization meant industry, and industry belonged to the Anglo-Germanic world. Everyone else was either a stepping stone or a mistake.

That he was himself a Jew did not prevent him from writing viciously anti-Jewish essays — betraying the same internalized racial hierarchies that governed much of 19th-century Europe. Marx may have dreamed of liberation, but he carried the chains of his own prejudices.

So why do so many in Latin America still kneel at his altar?

To cling to Marx today, for a Latin American, is to accept a master who called us subhuman — a thinker who justified our conquest in the name of progress, who spat on our heroes, and who never imagined we could think or fight for ourselves. It is not liberation — it is intellectual dependency.

We do not need to burn Marx’s books. But we must stop pretending he was on our side. He wasn’t. He never wanted to be. And we owe him nothing.

To think from Latin America is to break free not just from capitalism, but from every ideological empire that told us who we were, what we should become, and who had the right to speak for us.

Marx is not ours. And he doesn’t need to be.

Karl Marx contra América Latina

Hay una pregunta que debería hacerse más a menudo, aunque muchos la eviten por conveniencia o por dogma: ¿cómo puede un mexicano, un venezolano o cualquier latinoamericano seguir llamándose marxista, cuando Karl Marx despreciaba profundamente a sus pueblos, ridiculizaba su cultura y justificaba su sometimiento?

No se trata de una interpretación. Está en sus propias palabras, claras y brutales. Marx celebró la invasión de México por parte de Estados Unidos, glorificó la anexión de California como un acto “civilizador” y describió a los mexicanos como caricaturas degeneradas de los españoles. Su apoyo a los yanquis no fue incidental: los veía como herederos del progreso anglosajón, los agentes necesarios de la historia, encargados de abrir paso a la civilización sobre la barbarie.

En un pasaje notorio, Marx escribió:

“¿Y es acaso una desgracia que la magnífica California les haya sido arrebatada a los perezosos mexicanos, que no sabían qué hacer con ella? ¿Que los enérgicos yanquis explotarán las minas de California, aumentarán los medios de circulación, y, en pocos años, poblarán y desarrollarán el comercio en la costa del Pacífico, construirán ciudades, abrirán líneas de vapores y un ferrocarril de Nueva York a San Francisco? ¿Que por primera vez el Océano Pacífico será realmente abierto a la civilización? ¿Qué importa la ‘independencia’ de unos pocos españoles californianos o texanos, o la violación de la ‘justicia’ y otros principios morales, comparado con hechos de tal importancia histórica?”

Para Marx, la conquista no era una injusticia, sino una necesidad histórica. No veía valor en la soberanía de los “perezosos mexicanos”, ni legitimidad en el sufrimiento de un pueblo invadido. Lo que importaba era el ferrocarril. Lo que importaba era la industria. Lo que importaba era el modelo anglosajón de modernidad.

Y no fue un juicio aislado. Marx sostenía opiniones profundamente racistas sobre los pueblos hispánicos. Escribió:

“Los españoles ya están degenerados. Pero ahora un español degenerado —un mexicano— es un ideal: todos los vicios, la jactancia, la fanfarronería y el quijotismo de los españoles elevados a la tercera potencia, pero sin rastro de su solidez.”

Eso no es análisis político. Es un insulto racial. No es crítica. Es desprecio.

Ni siquiera perdonó a Simón Bolívar, el libertador de América del Sur. Marx lo despreció como cobarde, farsante y tiranuelo ridículo, simplemente porque Bolívar no encajaba en su modelo de revolución “correcta”. Marx no tenía paciencia para el criollo, el mestizo, el rebelde híbrido que luchaba fuera de la lógica de las revoluciones europeas. Su horizonte se limitaba a Londres, París, Berlín. Todo lo demás —desde los Andes hasta el Caribe— era periférico, infantil, irrelevante.

Incluso sus ideas sobre la lucha de clases fueron formuladas para las realidades europeas. Su esquema de etapas históricas —feudalismo, capitalismo, socialismo— es un mito lineal que jamás aplicó realmente a América Latina, África o Asia. Es una fantasía disfrazada de ciencia, una teología del progreso construida sobre chimeneas industriales y filosofía alemana.

Marx no solo fracasó en entender América Latina. Negó su valor. Su pensamiento estuvo moldeado por ideales eurocentristas: la civilización significaba industria, y la industria pertenecía al mundo anglogermano. Todos los demás eran obstáculos o errores.

Que fuera él mismo judío no impidió que escribiera ensayos virulentamente antijudíos, lo que revela cuán profundamente había interiorizado las jerarquías raciales y culturales de su tiempo. Marx pudo haber soñado con la liberación, pero cargaba con sus propios prejuicios.

Entonces, ¿por qué tantos en América Latina aún lo veneran?

Aferrarse a Marx hoy, siendo latinoamericano, es aceptar a un maestro que nos llamó subhumanos —un pensador que justificó nuestra conquista en nombre del progreso, que escupió sobre nuestros héroes, y que jamás imaginó que pudiéramos pensar o luchar por nosotros mismos. No es liberación —es dependencia intelectual.

No necesitamos quemar sus libros. Pero debemos dejar de fingir que estuvo de nuestro lado. No lo estuvo. Nunca quiso estarlo. Y no le debemos nada.

Pensar desde América Latina implica liberarse no solo del capitalismo, sino también de todo imperio ideológico que nos dijo quiénes éramos, qué debíamos ser y quién podía hablar por nosotros.

Marx no es nuestro. Y no tiene por qué serlo.

Leave a comment