Israel Centeno

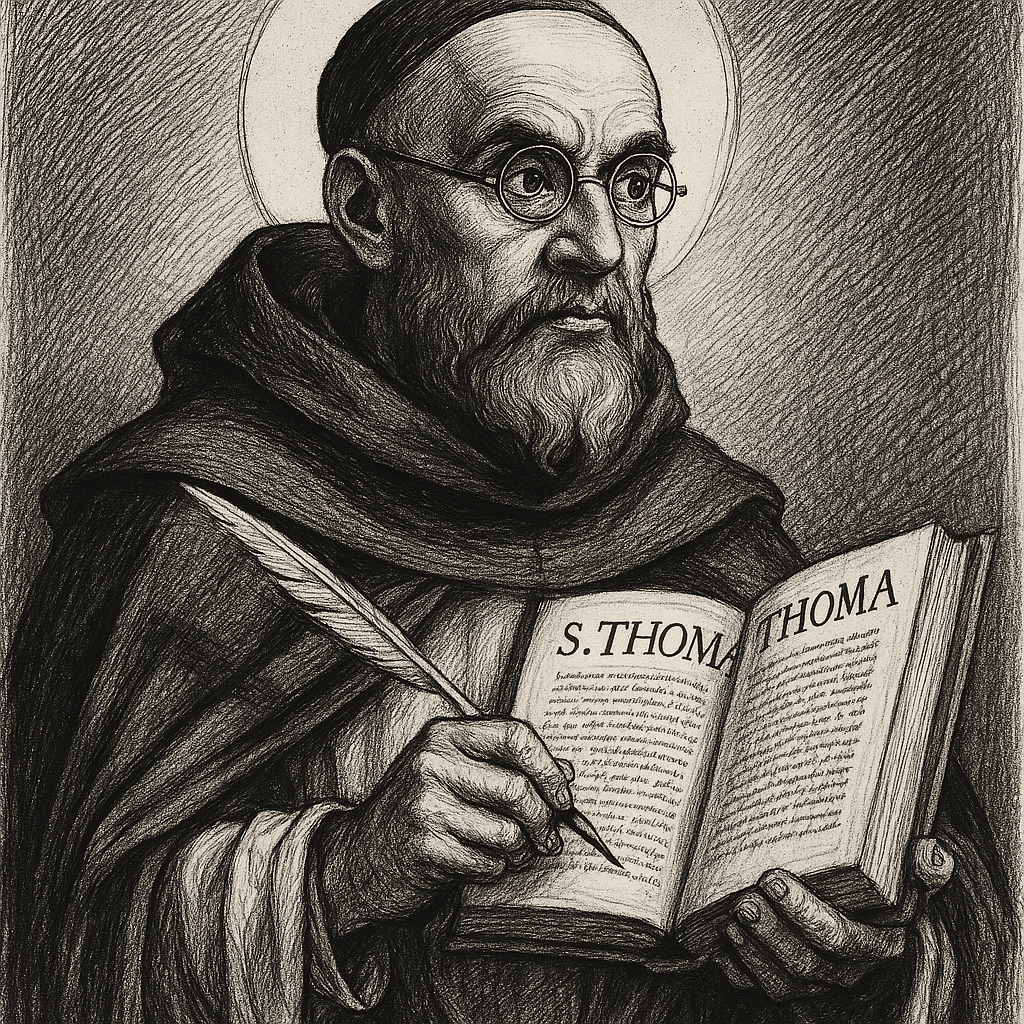

Playing Clever: The Enduring Intelligence of Thomism

— A brief defense of metaphysical clarity in the age of confusion

In an age dazzled by novelty and exhausted by contradiction, embracing Thomism is not a retreat to medieval nostalgia. It is, rather, the most intellectually strategic move one can make. To be a Thomist today is to be clever in the highest sense: to think with precision, argue with integrity, and live with metaphysical depth in a world that has forgotten the meaning of both truth and being.

Where contemporary philosophy often chases symptoms—identity, language games, subjectivity—Thomism strikes at roots. As Eleonore Stump has argued in Atonement and Wandering in Darkness, Thomistic thought offers a deeply unified vision of the human person, one that bridges metaphysics, moral psychology, and narrative understanding. Stump doesn’t merely repeat Aquinas; she shows how Thomism speaks meaningfully to the broken, to the suffering, to those wounded by both sin and secularism. That’s clever: to bring a 13th-century framework into dialogue with 21st-century wounds—and have it make more sense than any therapy manual.

Thomism is not simply systematic theology. It is a metaphysical realism so robust that it can absorb the best of modern thought without being swallowed by its confusions. As philosopher John Haldane puts it, Thomism is “the Aristotelian grammar of being refined by Christian metaphysics and elevated by revelation.” It does not fear reason, nor does it idolize it. It lets reason climb as far as it can go, and then allows faith to illumine what lies beyond—without contradiction, without coercion.

This is why being a Thomist is not simply clever but courageously intelligent. In a world where meaning is flattened to preference and truth is sacrificed to consensus, Thomism reminds us:

That esse (being) is not the same as essence. That causality includes final causes, not just efficient ones. That the soul is not a ghost in a machine but the form of the body, capable of reason, love, and grace. That God is not a being among beings, but ipsum esse subsistens—pure Act, the ground of all that is.

This isn’t cleverness in the smug sense. It’s the sobriety of someone who sees that the emperor of postmodernity has no clothes.

Indeed, one of the most compelling traits of Thomism is that it anticipates and outlives its critics. It survived Ockham’s nominalism, resisted the Cartesian ego, endured the Kantian divide, and now smiles gently at the deconstructionist obsession with difference. All these movements offered fragments. Aquinas offers a cosmos.

But above all, Thomism is clever because it has no need to panic. Its confidence lies not in academic fashion but in the clarity of its principles. That is why, as Étienne Gilson once wrote, “Thomism is not a philosophy among others. It is the metaphysics of the real.”

In a time when “deep” often means obscure and “complex” means confused, Thomism is both luminous and sane. It dares to say that truth exists, that the soul is real, that freedom matters, and that reason—when not mutilated—can lead us to the threshold of the divine.

To be a Thomist, then, is not to be passé. It is to be ahead of the game.

It is to play clever—with eternity in mind.

Leave a comment