Israel Centeno

Entre los primeros que escribieron sobre Cristo, el apóstol Pablo es, con toda probabilidad, la voz más inmediata en el tiempo a la muerte y resurrección del Señor. En su primera carta a los Corintios (1 Co 15, 3-8), Pablo transmite una proclamación que no inventa, sino que él mismo “recibió” (παρέλαβον, parelabon), empleando el término técnico de la tradición rabínica para la transmisión oral autorizada. El texto dice:

“Porque primeramente les he enseñado lo que asimismo recibí: que Cristo murió por nuestros pecados, según las Escrituras; que fue sepultado, y que resucitó al tercer día, según las Escrituras; que apareció a Cefas, y después a los Doce; luego apareció a más de quinientos hermanos a la vez, de los cuales muchos viven aún, y otros ya duermen. Después apareció a Jacobo; después a todos los apóstoles; y al último de todos, como a un abortivo, me apareció a mí.”

La mayoría de los exégetas modernos (James D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered, 2003; Larry Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ, 2003; N. T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God, 2003) reconocen en este pasaje la formulación de un credo cristiano primitivo, con estructura paralelística, ritmo memorizable y una teología pascual ya plenamente articulada. Joachim Jeremias y C. H. Dodd coinciden en situar este credo en Jerusalén, transmitido a Pablo durante su primera visita (Ga 1,18-19), es decir, tres a cinco años después de la crucifixión. Su proximidad temporal, unida a la presencia de testigos oculares vivos, lo convierte en la pieza documental más temprana del cristianismo.

Este núcleo kerigmático muestra que, desde el inicio, la fe en la muerte y resurrección de Jesús no fue el resultado de una lenta evolución literaria, sino el fundamento inalterable de la predicación apostólica. De hecho, el propio Pablo lo presenta como “lo primero” (ἐν πρώτοις), tanto en orden de transmisión como en jerarquía doctrinal.

Resulta difícil, incluso para la imaginación moderna, concebir que un grupo de pescadores galileos, acompañados por un doctor de la ley como Pablo, pudiese haber fabricado deliberadamente una red tan vasta y coherente de referencias entre el Antiguo Testamento y la vida de Jesús. Y más difícil aún si se considera el contexto: carecían de recursos técnicos, trabajaban en la expansión de un movimiento que en pocas décadas alcanzó Asia Menor, Siria, el norte de África y, según la tradición, la misma Hispania (cf. Ad Romanos 15, 24.28), todo ello en medio de persecuciones, viajes y fundación de comunidades.

Sin embargo, en muy poco tiempo, la totalidad del canon veterotestamentario comenzó a leerse como un mapa que conducía al Mesías: desde Job y Génesis, pasando por Deuteronomio, Reyes y Jueces, hasta los Salmos, el Cantar de los Cantares y la Sabiduría. No se trataba de un ejercicio literario retrospectivo, sino de una comprensión nueva, iluminada por el acontecimiento pascual. Como afirmará siglos después san Ireneo:

“Quoniam enim una eademque est dispositio salutis Dei, semper idem et idem est Deus, qui et legem dedit, et Evangelium instituit, et legem in Evangelio, et Evangelium in lege praedicavit” (Adversus Haereses IV, 9, 3).

“Porque uno y el mismo es el plan de salvación de Dios; siempre el mismo es el Dios que dio la Ley y estableció el Evangelio, que anunció la Ley en el Evangelio y el Evangelio en la Ley.”

Orígenes, en su Homilía sobre Josué (Hom. Jos. 2, 1), expresa el mismo principio hermenéutico:

“Toda la Escritura divina habla de Cristo, y toda la Escritura se cumple en Cristo.”

Los Padres entendieron que la lectura cristocéntrica de toda la Escritura no era una imposición desde el futuro, sino la revelación de un sentido ya presente, pero ahora plenamente manifiesto. Eusebio de Cesarea, en su Demonstratio Evangelica (II, 6), resume esta visión afirmando que la economía de Cristo es “el centro hacia el que convergen todas las profecías y figuras, como radios hacia un solo punto”.

La magnitud de esta obra —integrar los libros veterotestamentarios con los escritos apostólicos hasta culminar en el Apocalipsis—, llevada a cabo en tan breve tiempo y en circunstancias humanas adversas, sólo puede entenderse, como ya afirmaba la tradición, por la acción del Espíritu Santo. No había imprentas ni redes de comunicación centralizada; lo que había eran hombres y mujeres animados por una certeza inconmovible, conscientes de que la cruz y la resurrección de Cristo eran el centro de la historia.

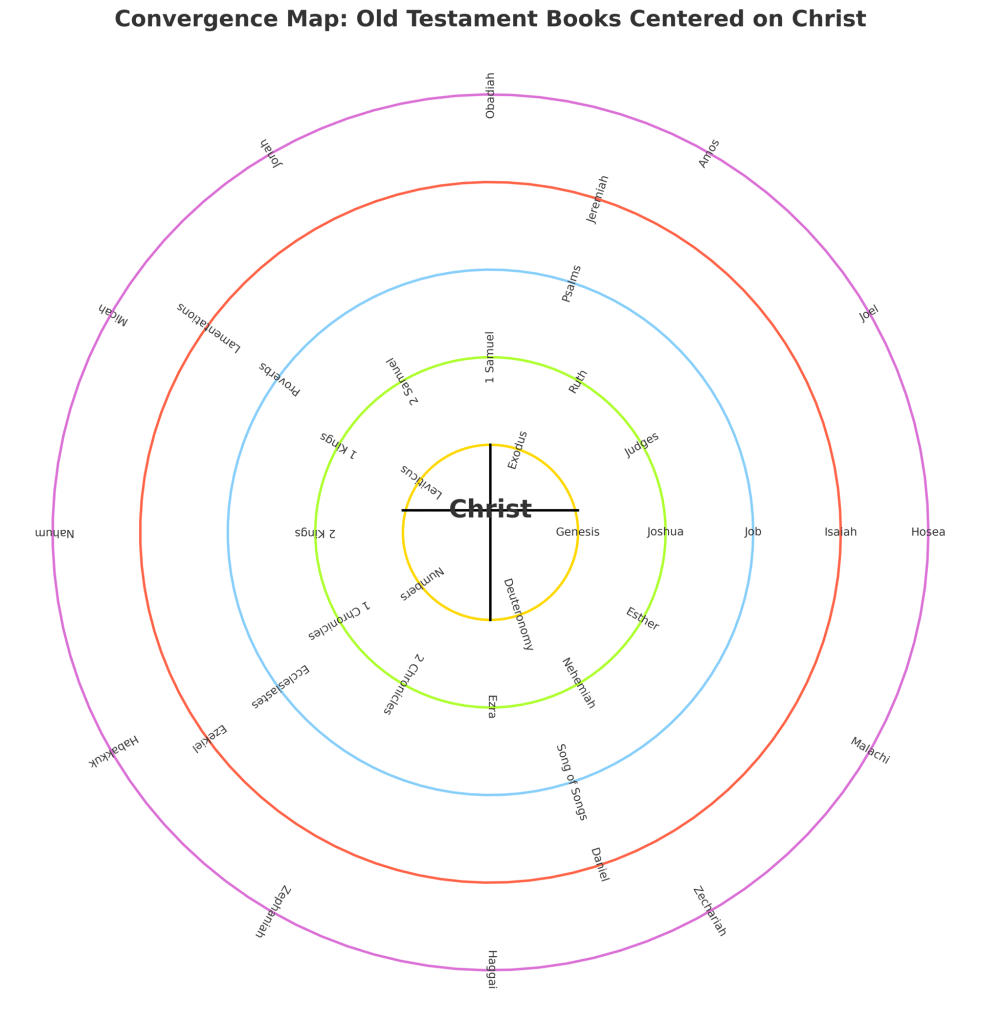

John Behr retoma esta intuición patrística al afirmar que la Biblia debe leerse con Cristo en el centro, con la cruz como eje que atraviesa el texto de abajo arriba y de izquierda a derecha, y círculos concéntricos formados por cada libro en torno a ella. En esa disposición, el Antiguo y el Nuevo Testamento, en su diversidad y en su unidad, confluyen en una misma figura: Cristo, que da coherencia, profundidad y sentido último a cada versículo, desde el primero hasta el último, haciendo de toda la Escritura un único testimonio que proclama la buena nueva de Dios hecho hombre.

Nota histórica:

El credo de 1 Corintios 15, probablemente formulado para la recitación litúrgica en las primeras comunidades, antecede a todos los Evangelios escritos y pertenece a un tiempo en que la mayoría de los testigos de la resurrección aún vivían. Su carácter memorizable y su estructura tripartita (muerte, sepultura, resurrección, cada una “según las Escrituras”) aseguran la transmisión fiel del núcleo de la fe. Esto demuestra que el cristianismo nació ya plenamente cristológico y pascual, no como el resultado tardío de un desarrollo teológico, sino como la proclamación original de los apóstoles, sellada y sostenida por la acción del Espíritu Santo

Christ at the Heart of All Scripture: Apostolic Witness, Tradition, and Patristic Reading

Among the first to write about Christ, the Apostle Paul is, in all likelihood, the voice closest in time to the Lord’s death and resurrection. In his First Letter to the Corinthians (1 Cor 15:3–8), Paul delivers a proclamation he did not invent, but which he himself “received” (παρέλαβον, parelabon), using the technical term from rabbinic tradition for the authorized oral transmission of teaching. The text reads:

“For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures; that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures; that He appeared to Cephas, then to the Twelve; then He appeared to more than five hundred brothers at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then He appeared to James; then to all the apostles; and last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared also to me.”

Most modern exegetes (James D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered, 2003; Larry Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ, 2003; N. T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God, 2003) recognize in this passage the formulation of a primitive Christian creed, with parallel structure, memorizable rhythm, and a fully articulated paschal theology. Joachim Jeremias and C. H. Dodd agree in situating this creed in Jerusalem, passed on to Paul during his first visit (Gal 1:18–19), that is, three to five years after the crucifixion. Its temporal proximity, together with the fact that most eyewitnesses were still alive, makes it the earliest documentary fragment of Christianity.

This kerygmatic nucleus shows that from the very beginning, faith in Jesus’ death and resurrection was not the result of a slow literary evolution, but the unalterable foundation of apostolic preaching. Indeed, Paul presents it as “of first importance” (ἐν πρώτοις), both in the order of transmission and in doctrinal hierarchy.

It is difficult, even for the modern imagination, to conceive that a group of Galilean fishermen, accompanied by a doctor of the Law like Paul, could have deliberately fabricated such a vast and coherent network of connections between the Old Testament and the life of Jesus. Still more difficult when one considers the context: they lacked technical resources, they were engaged in the expansion of a movement which, within a few decades, reached Asia Minor, Syria, North Africa, and—according to tradition—Hispania itself (cf. Romans 15:24, 28), all while enduring persecution, traveling, and founding communities.

Yet in a very short span of time, the entire Old Testament canon began to be read as a map leading to the Messiah: from Job and Genesis, through Deuteronomy, Kings, and Judges, to the Psalms, the Song of Songs, and the Wisdom of Solomon. This was not a retrospective literary exercise, but a new understanding illuminated by the paschal event. As St. Irenaeus would affirm centuries later:

“Quoniam enim una eademque est dispositio salutis Dei, semper idem et idem est Deus, qui et legem dedit, et Evangelium instituit, et legem in Evangelio, et Evangelium in lege praedicavit” (Against Heresies IV, 9, 3).

“For there is one and the same plan of salvation of God; the same God who gave the Law also established the Gospel, who proclaimed the Law in the Gospel and the Gospel in the Law.”

Origen, in his Homily on Joshua (Hom. Jos. 2, 1), expressed the same hermeneutical principle:

“The whole of divine Scripture speaks of Christ, and the whole of Scripture is fulfilled in Christ.”

The Fathers understood that a Christ-centered reading of all Scripture was not an imposition from the future, but the revelation of a meaning already present, now fully manifest. Eusebius of Caesarea, in his Demonstratio Evangelica (II, 6), summarizes this vision, stating that the economy of Christ is “the center towards which all prophecies and figures converge, like radii to a single point.”

The magnitude of this work—integrating the Old Testament books with the apostolic writings up to the Apocalypse—carried out in such a short time and under adverse human circumstances, can only be understood, as tradition affirms, through the action of the Holy Spirit. There were no printing presses, no centralized communication networks; there were only men and women animated by unshakable certainty, convinced that the cross and resurrection of Christ were the very center of history.

John Behr recaptures this patristic insight when he says that the Bible must be read with Christ at the center, with the cross as the axis running through the text from bottom to top and from left to right, and concentric circles formed by each book around it. In this arrangement, the Old and New Testaments, in their diversity and unity, converge in the same figure: Christ, who gives coherence, depth, and ultimate meaning to every verse, from the first to the last, making all of Scripture a single testimony proclaiming the Good News of God made man.

Historical Note:

The creed in 1 Corinthians 15, probably formulated for liturgical recitation in the earliest communities, predates all the written Gospels and belongs to a time when most witnesses to the resurrection were still alive. Its memorizable character and tripartite structure (death, burial, resurrection, each “according to the Scriptures”) ensured the faithful transmission of the faith’s core. This demonstrates that Christianity was born fully Christological and paschal—not as the late result of theological development, but as the original proclamation of the apostles, sealed and sustained by the action of the Holy Spirit.

Leave a comment