Israel Centeno

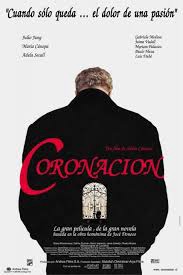

There are films that, when watched with calm attention, reveal far more than they appear to at first glance. Coronation (Chile, 2000), directed by Silvio Caiozzi and based on José Donoso’s novel, is one of them. At first it seems to be nothing more than a portrait of an aristocracy in decline, with dark mansions, dusty relics, and characters trapped in their own fragility. But if one lingers, another layer appears: that of a wounded humanity searching—though without knowing it—for a glimpse of redemption.

The mansion where the story unfolds is not just a backdrop: it is a symbol of a world collapsing under its own weight. The elderly Elisa Grey, lost among memories, and her grandson Andrés, solitary and empty, embody what happens when the soul is covered by dust and fear. Yet the decadence portrayed in Coronation is not only social: it also reflects a segmented Chile, where prejudice is not limited to class but carries with it a racial undertone that marks the indigenous and working classes. Estela, the young maid, embodies this tension: looked upon with both disdain and desire, caught between servitude and the hope of another life, her figure reveals that the fracture is not only of class but also of race. In her, the historical weight of inequality takes flesh and reminds us that the collapse of the mansion is also the collapse of a country that never fully reconciled itself with its diversity.

What is striking is that, amid all this ruin, the film is permeated with Catholic symbols: crucifixes, rosaries, confessions, references to purgatory. For some, these may sound like anticlerical satire or the remnants of a rigid upbringing. Yet seen from another perspective, they reveal what lies beneath: the need for repentance, the tension between justice and mercy, and the possibility of grace. The old woman forcing Estela to kiss a crucifix may appear cruel, but at the same time it conveys a truth: sin is never trivialized, and even in rigorist form, forgiveness still opens a door to redemption.

Andrés, the grandson, embodies most acutely the modern spiritual crisis. He lives aimlessly, collecting canes, muttering bitter phrases against God. His lament—“God must have been insane to make us conscious of meaninglessness”—is not pure atheism but rather an inverted theodicy, a reproach toward a God he still acknowledges but perceives as distant or cruel. Yet even in his confusion, Andrés lets slip moments of true love: his wish that Estela find happiness with her fiancé echoes Thomas Aquinas’s definition of love as to will the good of the other. His tragedy is that of a humanity that feels the spark of good but cannot order it, because it lacks faith and hope.

The film does not end in despair. The old woman’s final words—“Everything in the end is beautiful and I am not afraid”—work as a theological counterpoint. They are an unexpected echo of Julian of Norwich: All shall be well. What may appear like senile delirium can also be read as a glimpse of the beatific vision, the certainty that beyond ruin and sin, grace has the last word. It is the paradox of Christianity: that the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness does not overcome it.

What is fascinating is that neither Donoso nor Caiozzi wrote with catechetical intent. But that does not matter: true art, when it is honest and profound, always allows for a transcendent reading. That is its power. Today, when much of academic criticism allows itself to be carried away by fashionable labels—the woke movement, or wokeism, which turns every work into a pamphlet of class, race, or gender and denies it any other dimension—Coronation shows the opposite. A story can denounce social decay, portray racial tensions, and at the same time open itself to the spiritual. Cinema, when it is good, does not exhaust itself in ideology.

Watching the film, I thought that beyond the claustrophobic atmosphere, the strengths of its direction and performances, and the fidelity of Caiozzi’s adaptation of Donoso, there was space for a transcendent vision. Because every work of art that is truly good admits a transcendent gaze. And it should also be said that, although today the American Academy—caught up in fashionable woke movements—has often relegated Latin American literature to the corner of the exotic, our great literature—American in the broadest sense—owes William Faulkner far more than we sometimes care to admit. Donoso, Caiozzi, and even this half-forgotten Coronation in the memory of Chilean cinema remind us: where there is true art, there is always a door open to the eternal.

Leave a comment