bilingual

Israel Centeno

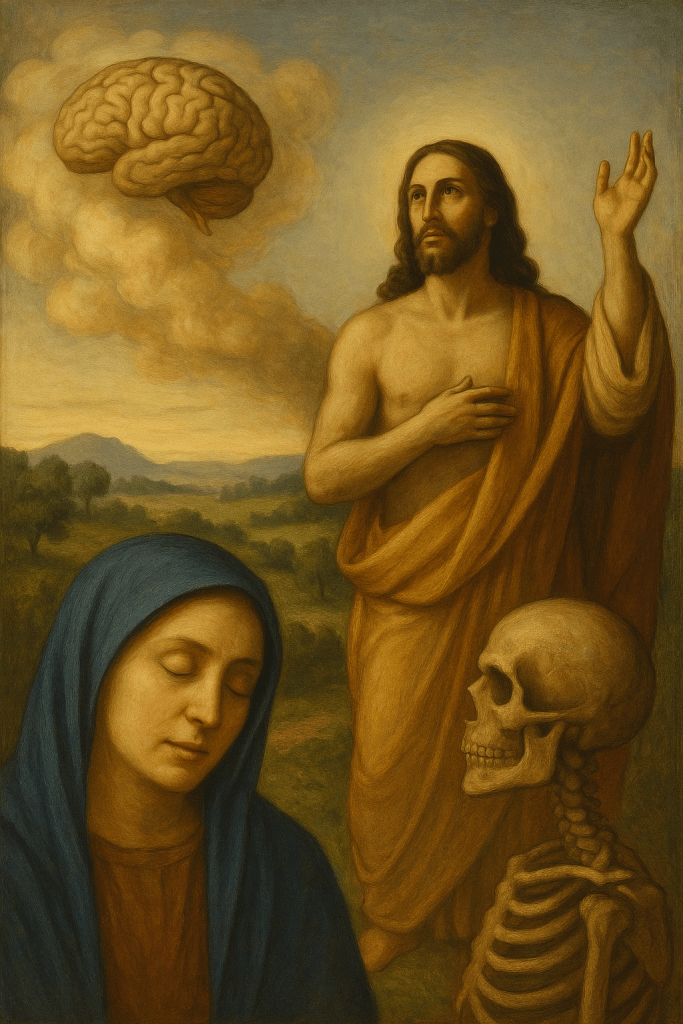

When I realize that I am alive, I am not merely noting a biological fact. I am recognizing something deeper: there is an I that knows itself to be alive. My body breathes, my cells divide, my nervous system processes information, but in becoming aware of it, another level of existence emerges. That “I live” is not the same as “my body lives.” Consciousness is the act by which I discover my being in the midst of biology.

If we were to accept that consciousness is material, we would need to show how the abstract could be secreted by the physical. But this is impossible: in biology, organs produce measurable substances —hormones, enzymes, neurotransmitters—; yet no abstract thought has weight, volume, or chemical composition. The structure of syntax or the concept of justice cannot be reduced to electric discharges. Consciousness is not secreted by the brain; rather, it makes use of the brain as its instrument of manifestation.

The Thomistic tradition offers clarity here. Thomas Aquinas taught that the soul is the form of the body: not a ghost added to matter, but the vital principle that organizes and sustains the biological. From conception, this substantial unity makes every human being a person. The rational soul is irreducible because it can grasp universals and the eternal. This ability to abstract is a sign of the spiritual and therefore of the immortal.

Eleonore Stump, in dialogue with contemporary analytic philosophy, has shown how this view avoids both Cartesian dualism and materialist reductionism. The person is a unity, yet with spiritual dimensions that cannot be reduced. Self-consciousness and the narrative structure of personal identity cannot be explained by neural correlates alone.

From neuroscience, Michael Egnor insists that the brain does not create the mind; it is its instrument. Just as a piano does not create music but makes it audible, the nervous system allows consciousness to express itself without being its source. Clinical evidence —patients retaining identity despite brain damage, near-death experiences, continuity of self in altered states— supports this intuition: the spiritual is not reducible to the material.

But Christianity does not stop there. We affirm not only an immortal soul but the resurrection of the dead. As Paul teaches: “What is sown in corruption is raised in incorruption; what is sown a natural body, is raised a spiritual body” (1 Cor 15:42-44). We will not rise as disembodied shadows, but with a glorified body, like Christ’s risen body.

Biology is seed, consciousness is anticipation, but resurrection is fulfillment. This life is like the chrysalis awaiting its final form. We are pilgrims toward the ultimate transformation: a glorified, incorruptible, immortal body, living eternally in the communion of God.

Notes (English)

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I, q. 75, on the nature of the soul. Michael Egnor, “The Mind and the Brain,” Evolution News, 2018. Eleonore Stump, Aquinas (Routledge, 2003); Wandering in Darkness (Oxford University Press, 2010). Bible, 1 Corinthians 15.

ESPAÑOL

Entre la biología y el espíritu: conciencia, alma y resurrección

Israel Centeno

Cuando me doy cuenta de que vivo, no estoy constatando un mero hecho biológico. Estoy reconociendo algo más profundo: que hay un yo que se sabe vivo. Mi cuerpo respira, mis células se multiplican, mi sistema nervioso procesa información, pero al advertirlo, surge otro nivel de existencia. Ese “yo vivo” no se reduce a “mi cuerpo vive”. La conciencia es el acto por el cual descubro mi ser en medio de lo biológico.

Si aceptáramos que la conciencia es material, tendríamos que mostrar cómo lo abstracto puede ser secretado por lo físico. Pero esto es imposible: en biología, los órganos producen sustancias medibles —hormonas, enzimas, neurotransmisores—; sin embargo, ningún pensamiento abstracto tiene peso, volumen ni composición química. No se puede reducir la estructura de una sintaxis o la noción de justicia a descargas eléctricas. La conciencia no es una segregación del cerebro, sino que se sirve del cerebro para manifestarse.

La tradición tomista ofrece claridad aquí. Santo Tomás de Aquino enseña que el alma es la forma del cuerpo: no un fantasma añadido, sino el principio vital que organiza y sostiene lo biológico. Desde la concepción existe esa unión sustancial que hace de cada ser humano una persona. El alma racional es irreductible porque puede pensar lo universal y lo eterno. Esa capacidad de abstraer es ya signo de lo espiritual y, por tanto, de lo inmortal.

Eleonore Stump, en diálogo con la filosofía analítica, muestra cómo esta visión evita tanto el dualismo cartesiano como el reduccionismo materialista. La persona es una unidad, pero con dimensiones espirituales irreductibles. La autoconciencia y la capacidad de narrar la propia vida no se explican por simples correlatos neuronales.

Desde la neurociencia, Michael Egnor insiste en que el cerebro no crea la mente: es su instrumento. Así como un piano no crea la música, sino que la hace audible, el sistema nervioso permite que la conciencia se exprese, sin ser su fuente. Los fenómenos clínicos —pacientes que mantienen identidad pese a daño cerebral, experiencias cercanas a la muerte, continuidad del yo en estados alterados— apoyan esta intuición: lo espiritual no se reduce a lo material.

Pero el cristianismo no se detiene ahí. No solo afirmamos un alma inmortal: proclamamos la resurrección de los muertos. Como enseña San Pablo: “Lo que se siembra en corrupción, resucita en incorrupción; lo que se siembra cuerpo animal, resucita cuerpo espiritual” (1 Cor 15, 42-44). No resucitamos como sombras desencarnadas, sino con un cuerpo glorioso, semejante al de Cristo resucitado.

La biología es semilla, la conciencia es anticipo, pero la resurrección es la plenitud. Esta vida es como el tránsito de la crisálida que espera desplegar su forma definitiva. Somos peregrinos hacia la transformación final: un cuerpo glorificado, incorruptible, inmortal, en la comunión eterna de Dios.

Notas (Español)

Santo Tomás de Aquino, Suma Teológica, I, q. 75, sobre la naturaleza del alma. Michael Egnor, “The Mind and the Brain,” Evolution News, 2018. Eleonore Stump, Aquinas (Routledge, 2003); Wandering in Darkness (Oxford University Press, 2010). Biblia, 1 Corintios 15

Leave a comment