Spanish/English

Isabel de La Trinidad

Prólogo

Hay textos que nacen de la plenitud de la vida, y otros que surgen en la víspera de la muerte. El Último Retiro de Isabel de la Trinidad pertenece a esta segunda categoría: es la obra de una joven carmelita de apenas veintiséis años que, consumida por la enfermedad, escribe lo que sabe será su despedida.

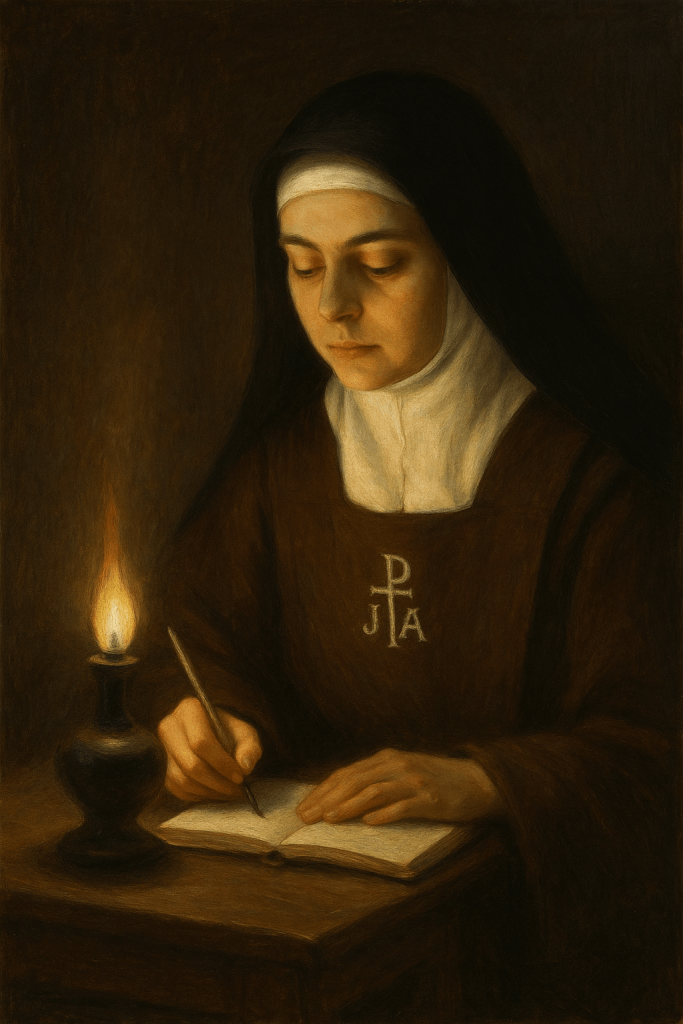

Pero lo que aquí se ofrece no es un testamento frío, ni un tratado espiritual elaborado con calma. Son notas breves, escritas en noches de insomnio, entre dolores insoportables y fatigas que casi la hacen desvanecerse. El cuaderno nace bajo la luz tenue de una pequeña lámpara, símbolo de su fe ardiente: una fe que, en medio de la oscuridad, se atreve a confesar que Dios es fuego devorador y, al mismo tiempo, luz de amor.

El lector no encontrará aquí teorías de mística ni teología especulativa. Isabel no escribe como teórica, sino como testigo. Sus palabras tienen el peso de lo vivido: el lecho se convierte en altar, la enfermedad en noviciado para el Cielo, el sufrimiento en comunión con el Crucificado. Todo está atravesado por un solo deseo, repetido con insistencia: ser “alabanza de gloria”, Laudem Gloriae. Ese es el nombre que ella misma elige para sí, y que convierte su vida entera en un himno a la Trinidad.

Al mismo tiempo, estas páginas tienen un aire sorprendentemente universal. Aunque escritas en la clausura de un Carmelo de Dijon, en 1906, resuenan con la misma fuerza en el lector de hoy, porque tocan lo esencial: la necesidad de silencio interior, la presencia de Dios en lo más profundo, la unión con Cristo en su cruz y la esperanza firme en una vida eterna.

En El Último Retiro, Isabel no pretende enseñar nada nuevo; pretende —como María— guardar en el corazón la Palabra de Dios y dejar que ella lo ilumine todo. La Escritura se convierte en su alimento diario: no como cita erudita, sino como palabra viva que consuela, juzga y transforma. Su oración es simple y radical: escuchar, asentir, amar.

Este cuaderno, entonces, no debe leerse como un manual, sino como lo que realmente es: un diario del alma, una serie de relámpagos escritos en el umbral de la eternidad. El valor de estas páginas no está en la perfección de su estilo, sino en la transparencia de su espíritu. Isabel escribe desde “el abismo sin fondo” de su alma abierta a Dios, y desde allí nos invita a mirar más allá del sufrimiento, hacia el horizonte donde todo se transforma en gloria.

Leer El Último Retiro es acompañar a una joven mujer en su paso hacia la eternidad, y dejarse enseñar por ella que la verdadera vida comienza cuando ya no nos pertenecemos, sino que nos dejamos poseer por el Amor.

Introducción

Desde su celda en la enfermería, el 14 de agosto de 1906, Isabel de la Trinidad anuncia a la Madre María de Jesús (priora del Carmelo de Paray-le-Monial, y su antigua priora en el momento de su entrada al Carmelo, que acababa de llegar a Dijon) que la tarde siguiente comenzará su retiro anual. Ella sabe muy bien que será el último.

“Me alegra tanto encontrarte en este gran viaje. Parto con la Santísima Virgen en la víspera de su Asunción para prepararme a la vida eterna. Nuestra Madre [Madre Germaine] me ha hecho tanto bien al decirme que este retiro será mi noviciado para el Cielo, y que el 8 de diciembre [quinto aniversario de su toma de hábito], si la Santísima Virgen ve que estoy lista, me revestirá con su manto de gloria. La bienaventuranza me atrae cada vez más; entre mi Maestro y yo, de eso es de lo único que hablamos, y toda su obra en mí es prepararme para la vida eterna” (Carta 306).

La misma idea se repite en la carta 307, escrita al día siguiente. Isabel había “pedido la gracia de un retiro” hasta el “31 de agosto.”

La priora, que apenas desde hacía unos días tenía en sus manos el cuaderno de El Cielo en la Fe, y que ya pensaba en la circular necrológica que pronto tendría que redactar sobre la joven carmelita moribunda, le hizo un pedido aparentemente inocente: que “anotara sencillamente las luces espirituales” que recibiera. Isabel comprendió y aceptó con una sonrisa.

Descripción y datación

Un pequeño cuaderno, escrito con tinta, nos confía el testimonio de sus intuiciones espirituales. No fue hasta el 24 de septiembre que Isabel entregó sus notas a la priora, envueltas en un pobre papel pardo (todavía conservado), con esta inscripción: “El último retiro de Laudem Gloriae.”

¿Es un “título” (realmente muy adecuado), como sugería la Madre Germaine? ¿O simplemente una indicación cronológica —“este retiro ha sido el último, pronto ya no estaré más”—, como parece más probable?

Al abrir el cuaderno leemos en la parte superior de la primera página, antes del texto: “Jueves 16 de agosto. Primer día.” Nada más. Isabel no dio título alguno. Como en El Cielo en la Fe, esta ausencia indica al menos una gran falta de pretensión.

El “día 16” nos lleva lógicamente al 31 de agosto como conclusión del retiro; y en efecto, el texto parece estar en sintonía con la liturgia de ese día, la Dedicación de las Iglesias Carmelitas. Sin embargo, Isabel no entregó su cuaderno hasta el 24 de septiembre y este “día dieciséis” coincide también, de alguna manera, con el Poema 115, preparado para esa misma fecha.

Por ello, cabe preguntarse si la redacción terminó realmente el 31 de agosto o si continuó después. O incluso si el cuaderno es una segunda versión de un borrador que Isabel destruyó. Es imposible resolverlo. Lo más probable es que los escritos correspondan efectivamente a los dieciséis días de retiro, redactados directamente en el cuaderno.

La caligrafía, lenta y laboriosa, da testimonio del agotamiento físico de Isabel.

Un tanto revisado, el texto fue publicado en la primera edición de los Souvenirs en 1909.

Un retiro de una enferma

A causa de la enfermedad de Isabel, su retiro no se desarrolla como en años anteriores. Por una parte, ya no participa con la comunidad ni en el Oficio Divino ni en las comidas; por otra, la soledad y el silencio durante el día no pueden ser absolutos. Recibe las visitas de las enfermeras, que le traen el escaso alimento que todavía puede ingerir, le arreglan la cama de la agotada enferma, limpian la habitación y la atienden. También está la visita periódica del médico.

En la enfermería vive al menos otra hermana (ya anciana, que morirá cinco días después que Isabel). Durante esos días, Isabel vuelve a ver a su madre en la sala de visitas de la enfermería (cf. Carta 308, nota 3). No quiso hablarle a su familia del retiro para no privarles de la consolación de un último encuentro antes de su muerte cercana.

En este período no siempre permanece en su celda: aprovecha los días de “buen tiempo” para salir a la terraza. Isabel pasa sus jornadas en oración, lectura, silencio y descanso. Es por la tarde, cuando es menos probable que la interrumpan las visitas de las enfermeras, cuando redacta sus notas de retiro.

La Madre Germaine precisa que estas páginas fueron “escritas durante noches dolorosamente insomnes y bajo el asalto de dolores tan violentos que la pobre niña sentía que iba a desmayarse” (Souvenirs, 215). La pequeña lámpara que ilumina sus escritos se convierte en símbolo: el de su deseo de ofrecerse al “fuego devorador” de Dios (Último Retiro 19), sostenida únicamente por “la hermosa luz de la fe… la única que debe iluminar mi camino hacia el Esposo” (Último Retiro 10).

Las notas del retiro no son necesariamente la transcripción inmediata de su oración de cada día ni de sus lecturas bíblicas diarias. La oración de Isabel no está hecha tanto de ideas, sino de una atención perseverante, amorosa y creyente a la Presencia que habita en ella y al Amor que la reclama. Es la totalidad de pensamientos expresados en El Último Retiro lo que refleja su vida interior en esos días.

Claves de lectura

- Trasfondo autobiográfico

El Último Retiro posee un fuerte valor autobiográfico y un marcado significado cronológico. Refleja las realidades espirituales dominantes de aquellos dieciséis días, tal como lo deseaba la Madre Germaine. Isabel no habla como teórica, sino como testigo. - Presencia del sufrimiento

El texto está atravesado por el dolor físico, la aceptación espiritual y la dimensión redentora del sufrimiento. Isabel lo vive como conformidad con el Crucificado. - Cristocentrismo

Cristo es el “Maestro”, el centro absoluto de su vida interior. Y junto a Él, María, la Madre que enseña a sufrir como Él. - El alma de una sola idea

La gran idea de Isabel es la unión con Dios, en la tierra como en el Cielo. Esa unión es ya participación en la eternidad y fuente de alabanza. - El uso de la Escritura

La Escritura es su alimento. No la cita como erudición, sino como palabra viva que se hace carne en su sufrimiento y en su oración. Cada cita es un acto de escucha y de entrega.

Conclusión

¿Es El Último Retiro una “obra maestra”? No. Es más que eso: no un tratado estético, sino un grito de amor y de verdad.

Nace de una sed radical de Dios, de la entrega total de Isabel al “Crucificado por amor.”

Es, en definitiva, el grito del alma ante el exceso de amor de Dios, escrito en el umbral de la eternidad.

El soplo de Dios pasa del corazón a la pluma.

Primer día — Jueves 16 de agosto

“Nescivi” — “Ya no supe nada.”

Así canta la Esposa del Cantar de los Cantares después de haber sido introducida en la “bodega interior.”

Me parece que este debe ser también el estribillo de una alabanza de gloria en este primer día del retiro, en el que el Maestro la hace penetrar en las profundidades del abismo sin fondo, para enseñarle a cumplir la obra que será suya por toda la eternidad, y que ya debe comenzar a realizar en el tiempo, pues el tiempo no es sino la eternidad que ha comenzado y aún sigue en curso.

“Nescivi” — ya no sé nada; no quiero saber nada, sino “conocerle a Él, compartir sus sufrimientos, asemejarme a Él en su muerte.”

Porque “a los que Dios conoció de antemano, también los predestinó a ser conformes a la imagen de su Hijo divino,” aquel que fue crucificado por amor.

Cuando esté totalmente identificada con este Modelo divino, cuando haya pasado completamente a Él y Él a mí, entonces cumpliré mi vocación eterna: aquella para la cual Dios “me eligió en Él” in principio; la que continuaré in aeternum cuando, sumergida en el seno de mi Trinidad, sea la alabanza perpetua de su gloria, Laudem Gloriae Ejus.

“Nadie ha visto al Padre,” nos dice san Juan, “sino el Hijo y aquel a quien el Hijo quiera revelarlo.”

Me parece que también podemos decir:

“Nadie ha penetrado las profundidades del misterio de Cristo, excepto la Santísima Virgen.”

San Juan y María Magdalena penetraron profundamente este misterio; san Pablo habla con frecuencia de “la inteligencia de este misterio que le fue concedida.”

Y, sin embargo, ¡cuán en sombras permanecen todos los santos cuando se contempla la luz de la Santísima Virgen!

Este es el inefable secreto que ella guardaba en su mente y meditaba en su corazón, un secreto que ninguna lengua puede expresar ni pluma describir.

Esta Madre de la gracia formará mi alma, para que su pequeña hija sea una imagen viva y resplandeciente de su Primogénito, el Hijo del Eterno,

Aquel que fue la perfecta alabanza de la gloria del Padre.

📜 Santa Isabel de la Trinidad, El Último Retiro

(The Complete Works, vol. 1, edición revisada, ICS Publications)

The Last Retreat

Prologue

There are texts that are born from the fullness of life, and others that arise on the eve of death. The Last Retreat of Elizabeth of the Trinity belongs to the latter: it is the work of a young Carmelite, only twenty-six years old, who, consumed by illness, writes what she knows will be her farewell.

Yet what is offered here is not a cold testament, nor a carefully composed spiritual treatise. These are brief notes, written on sleepless nights, amid unbearable pain and fatigue that nearly made her faint. The notebook was born under the dim light of a small lamp—a symbol of her burning faith: a faith that, in the midst of darkness, dares to confess that God is a consuming fire and, at the same time, a light of love.

The reader will not find here theories of mysticism or speculative theology. Elizabeth writes not as a theorist, but as a witness. Her words bear the weight of lived experience: the bed becomes an altar, illness a novitiate for Heaven, suffering a communion with the Crucified. Everything is crossed by a single desire, repeated insistently—to be a “praise of glory,” Laudem Gloriae. That is the name she chooses for herself, transforming her whole life into a hymn to the Trinity.

At the same time, these pages have a surprisingly universal tone. Although written in the enclosure of a Carmelite convent in Dijon in 1906, they still resonate powerfully with today’s reader, for they touch the essential: the need for inner silence, the presence of God at the deepest level, union with Christ on the cross, and the firm hope in eternal life.

In The Last Retreat, Elizabeth does not seek to teach anything new; she seeks—like Mary—to keep the Word of God in her heart and allow it to illumine everything. Scripture becomes her daily nourishment: not as scholarly quotation, but as living word that consoles, judges, and transforms. Her prayer is simple and radical: to listen, to consent, to love.

This notebook, then, should not be read as a manual, but as what it truly is: a diary of the soul, a series of flashes written at the threshold of eternity. The value of these pages lies not in stylistic perfection but in the transparency of her spirit. Elizabeth writes from “the bottomless abyss” of her soul opened to God, and from there she invites us to look beyond suffering, toward the horizon where all is transformed into glory.

To read The Last Retreat is to accompany a young woman on her passage into eternity and to let her teach us that true life begins when we no longer belong to ourselves, but allow ourselves to be possessed by Love.

Introduction

From her cell in the infirmary, on August 14, 1906, Elizabeth of the Trinity announced to Mother Marie of Jesus (prioress of the Carmel of Paray-le-Monial, and her former prioress at the time of her entrance into Carmel, who had just come to Dijon) that the next evening she would begin her annual retreat. She knew very well that it would be her last.

“I am delighted to meet you on my great journey. I leave with the Blessed Virgin on the eve of her Assumption to prepare myself for eternal life. Our Mother [Mother Germaine] did me so much good by telling me that this retreat would be my novitiate for Heaven, and that on the 8th of December [fifth anniversary of her clothing], if the Blessed Virgin sees that I am ready, she will clothe me in her mantle of glory. Beatitude attracts me more and more; between my Master and me that is all we talk about, and His whole work is to prepare me for eternal life” (Letter 306).

The same idea appears again the following day in Letter 307. Elizabeth had “asked for the grace of a retreat” until “the 31st of August.”

The prioress, who had held in her hands for just a few days the notebook of Heaven in Faith and had already begun to think about the obituary circular she would soon have to write for the dying young nun, made an apparently innocent request: that Elizabeth “simply write down any spiritual insights she might receive.” Elizabeth understood and accepted with a smile.

Description and Dating

A small notebook, written in ink, entrusts to us the account of her spiritual insights. It was not until September 24 that Elizabeth gave her notes to the prioress, wrapped in poor brown paper (still preserved) with this inscription: “The Last Retreat of Laudem Gloriae.”

Is it a “title” (indeed a fitting one), as Mother Germaine suggested? Or rather a simple chronological indication—“this retreat has been my last; soon I will be no more”?

Upon opening the notebook, we read at the top of the first page before the text begins: “Thursday, August 16. First day.” Nothing more. Elizabeth gives no title. As in Heaven in Faith, this absence signals at least a great lack of pretension.

The “16th day” logically leads us to August 31 for the conclusion of the retreat; the text, in fact, aligns with the liturgy of that day—the Dedication of the Churches of Carmel. However, Elizabeth did not hand over her notebook until September 24, and this “sixteenth day” also corresponds, in a sense, to Poem 115, prepared for that same date.

Thus, one might ask whether the writing truly ended on August 31 or continued afterward—or whether the notebook was a second draft of a first version that Elizabeth may have destroyed. The question cannot be resolved. What seems most probable is that the writing coincided with the sixteen days of the retreat and was written directly in the notebook.

The handwriting, slow and painstaking, bears witness to Elizabeth’s physical exhaustion. Slightly revised, the text was published in the first edition of the Souvenirs in 1909.

A Retreat of an Invalid

Because of Elizabeth’s illness, her retreat did not unfold as in previous years. She no longer joined the community for the Divine Office or meals, and her solitude and silence could not be absolute. The infirmarians brought her the little nourishment she could still take, tended her bed, cleaned her cell, and cared for her. The doctor came regularly.

At least one other sister—very old and soon to die five days after Elizabeth—shared the infirmary. Elizabeth saw her mother again during these days in the infirmary parlor (cf. Letter 308, n. 3). She did not wish to tell her family about the retreat, so as not to deprive them of the consolation of one last visit before her approaching death.

During this period she did not always remain in her cell: she took advantage of “good weather” to “go out on the terrace.” Elizabeth spent her days in prayer, reading, silence, and rest. It was in the evenings, less likely to be interrupted by visits, that she wrote her retreat notes.

Mother Germaine tells us these pages were “written during painfully sleepless nights and amid such violent suffering that the poor child felt she would faint” (Souvenirs, 215). The small lamp that lit her writing became a symbol of her desire to offer herself to “the consuming fire” of God (Last Retreat 19), sustained only by “the beautiful light of faith… which alone should illumine my path as I go to meet the Bridegroom” (Last Retreat 10).

These notes do not necessarily record her prayer of that exact day, nor her daily readings. Her prayer consisted less of ideas than of loving, persevering attention to the Presence dwelling within her and the Love claiming her. The whole of her reflections in the Last Retreat reveal the interior life she lived during those days.

Keys to Reading

- Autobiographical background

The Last Retreat has a strong autobiographical character and chronological significance. It reflects the dominant spiritual realities of those sixteen days, as Mother Germaine desired. Elizabeth does not write as a theoretician, but as a witness. - Presence of suffering

The text is marked by physical pain, spiritual acceptance, and the redemptive meaning of suffering. Elizabeth lives it as conformity with the Crucified. - Christocentrism

Christ is the “Master,” the absolute center of her inner life. Beside Him stands Mary—the Mother who teaches her to suffer as He did. - The soul of one idea

Elizabeth’s great idea is union with God, on earth as in Heaven. That union is already participation in eternity and the source of praise. - Use of Scripture

Scripture is her sustenance. She does not quote it for erudition, but as living word that becomes flesh in her suffering and prayer. Each quotation is an act of listening and surrender.

Conclusion

Is The Last Retreat a “masterpiece”? Not in the aesthetic sense. It is not a polished treatise, but a cry.

It is born from a radical thirst for God, from Elizabeth’s total surrender to the “Crucified by love.”

It is, ultimately, the cry of a soul before the excess of God’s love, written on the threshold of eternity.

The breath of God passes from heart to pen.

Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity

The Last Retreat

First Day — Thursday, August 16

“Nescivi” — “I no longer knew anything.”

Thus sings the Bride of the Canticle of Canticles after having been brought into the “inner cellar.”

It seems to me that this must also be the refrain of a praise of glory on this first day of retreat, in which the Master makes her enter into the depths of the bottomless abyss, so that He may teach her to fulfill the work that will be hers for eternity, and which she must already begin to perform in time — for time is eternity begun and still unfolding.

“Nescivi” — I no longer know anything; I no longer wish to know anything except “to know Him, to share in His sufferings, and to become like Him in His death.”

“For those whom God foreknew, He also predestined to be conformed to the image of His divine Son,” the One crucified by love.

When I am wholly identified with this divine Exemplar, when I have wholly passed into Him and He into me, then I will fulfill my eternal vocation: the one for which God “chose me in Him” in principio, the one I shall continue in aeternum when, immersed in the bosom of my Trinity, I shall be the unceasing praise of His glory — Laudem Gloriae Ejus.

“No one has seen the Father,” says Saint John, “except the Son and the one to whom the Son chooses to reveal Him.”

It seems to me that we can also say:

“No one has penetrated the depths of the mystery of Christ except the Blessed Virgin.”

John and Mary Magdalene entered deeply into this mystery; Saint Paul often speaks of “the understanding of it that was given to him.”

And yet, how all the saints remain in shadow when we look at the light of the Blessed Virgin!

This is the unspeakable secret that she kept in mind and pondered in her heart — a secret no tongue can tell and no pen can describe.

This Mother of grace will form my soul, so that her little child may become a living and radiant image of her First-Born, the Son of the Eternal,

He who was the perfect praise of His Father’s glory.

📜 Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity, The Last Retreat

(The Complete Works, Vol. 1 — Revised Edition, ICS Publications)

Leave a comment