Los cuatro cuartetos a la luz del tiempo, el sufrimiento y la caridad.

Israel Centeno

(Subo el PDF con El Papel Literario de El Nacional de noviembre 22 2025) Aquí entre otros compañeros escritores.

Los cuatro cuartetos a la luz del tiempo, el sufrimiento y la caridad.

Israel Centeno

(Subo el PDF con El Papel Literario de El Nacional de noviembre 22 2025) Aquí entre otros compañeros escritores.

Israel Centeno

El dolor tiene memoria.

Y no porque la herida sea débil, sino porque el alma recuerda en presente.

Cuando evocamos una injusticia, no recuperamos solo un hecho pasado:

reactivamos un sentido inconcluso.

El recuerdo vuelve porque quedó incompleto, porque exige verdad, porque desea justicia.

El alma humana no tolera el mal como un simple dato:

lo lee como una fractura del ser,

y por eso duele al recordarlo.

La memoria actualiza lo que aún no ha sido resuelto.

Pero aquí entra el misterio:

cada recuerdo es potencia.

Puede reabrir la herida

o puede transformarse en semilla.

Puede repetir el ciclo

o puede iluminarlo.

Entre esos dos caminos se juega nuestra libertad.

Cristo propone algo desconcertante:

perdonar setenta veces siete.

No es sentimentalismo.

No es olvido.

Y tampoco es renuncia a la justicia.

Es una invitación a sacar la herida

del dominio del tiempo

y colocarla en la eternidad.

Perdonar no significa que el mal no importe.

Significa que el mal no tendrá la última palabra sobre tu identidad.

El perdón cristiano rompe el ciclo.

Es una interrupción ontológica.

Es el acto por el cual el alma se niega a ser moldeada por la herida

y se abre a la luz de Dios.

“Poner la otra mejilla” es un gesto incomprendido.

No es pasividad, ni docilidad, ni ingenuidad.

Es una revolución interior:

un rechazo a la lógica del agresor.

Significa:

“No me convertiré en lo que me has hecho.”

“No permitiré que tu mal dicte mi respuesta.”

“La violencia no tendrá eco en mí.”

Ese gesto es acto puro:

la voluntad tocando su propia libertad.

Lo que podría haber sido un reflejo automático —resentimiento, venganza, repetición—

se transforma en una decisión luminosa.

Aquí se ve la hondura del Evangelio:

solo quien ama puede romper la cadena del odio.

La pregunta —“¿Quién habita entre el fue y el aún no soy?”—

toca el corazón del discipulado cristiano.

Ese espacio intermedio es donde vive el creyente.

No somos aún la gloria prometida,

pero ya no somos lo que éramos en la caída.

Habitamos un umbral:

la potencia esperando convertirse en plenitud.

Y es allí donde recordamos el dolor.

Donde perdonamos.

Donde avanzamos a tientas hacia la luz.

Es natural que duela.

Pero en ese dolor —cuando se entrega a Dios—

crece algo invisible:

fortaleza, humildad, claridad, ternura.

La gracia trabaja en silencio dentro de la memoria.

Cristo no pide que olvidemos.

Pide que entreguemos.

Él sabe que el corazón humano no puede borrar el pasado:

pero sí puede recibirlo transformado.

Cuando Dios entra en la herida:

– el hecho permanece,

– pero el veneno se disipa;

– la memoria ya no acusa,

– sino que ilumina.

La herida se vuelve ventana.

Y lo que dolía

se convierte en lugar de encuentro con Dios.

Ese es el verdadero milagro:

no que dejemos de recordar,

sino que empecemos a recordar desde la gracia.

Vendrá un día —cuando la potencia alcance su acto total—

en que veremos cada dolor bajo una luz distinta.

Comprenderemos por qué volvió tantas veces.

Comprenderemos por qué perdonar fue tan arduo.

Comprenderemos cómo cada herida entregada a Dios

se convirtió en gloria.

Y entonces sabremos que el perdón

no fue una obligación moral,

sino la disciplina de los santos:

el modo humano de participar

en la misma victoria del Crucificado.

Porque el perdón es la manera en que el alma aprende a vivir

con la luz del Reino

mientras aún camina

por las sombras del tiempo.

VOLVER AL DIOS QUE LLAMA POR NUESTRO NOMBRE

Israel Centeno

El primer mandamiento no llegó como una prohibición fría, sino como una brújula para el corazón:

“Escucha, Israel: el Señor es nuestro Dios, el Señor es Uno.”

Esa afirmación, antes que norma, es identidad. Es la voz que nos recuerda quiénes somos y hacia dónde gira la vida. Y, sin embargo, desde que esa voz resonó, el ser humano ha tenido la tendencia constante a fabricar ídolos, aun cuando se cree demasiado lúcido, demasiado moderno o demasiado iconoclasta como para caer en ellos.

La verdad es más simple y más dolorosa: no sabemos vivir sin adorar algo.

El episodio del becerro de oro lo revela con exactitud. Moisés sube al encuentro de Dios y el pueblo, sintiéndose huérfano, se desespera. No soporta la espera, no tolera el silencio de la montaña. Entonces hace lo que hace el corazón humano cuando pierde el centro: construye un dios visible. No por rebeldía, sino por miedo. No por paganismo, sino por vulnerabilidad. No por maldad, sino por abandono.

El becerro de oro es un espejo.

No muestra un pueblo primitivo, sino la anatomía espiritual del hombre: cuando la fe se debilita, la reemplaza; cuando Dios calla, inventa un sustituto; cuando no ve, fabrica una imagen; cuando no siente, se arrodilla ante lo que brilla.

La idolatría no desaparece, solo cambia de forma.

Después vendrán los cuarenta años de desierto, ese largo trabajo de purificación. No fue un castigo, sino una escuela: aprender a vivir sin depender de lo que se toca, se ve o se manipula. Aprender a confiar en el Dios que habla desde el silencio y alimenta desde la nada. Era necesario vaciarse para poder reconocerlo cuando, en la plenitud del tiempo, se hiciera carne y habitara entre nosotros.

La Encarnación es la gran ruptura: el Dios único se acerca, se deja ver, se deja tocar. Y, sin embargo, al revelarse como Hijo, nos introduce en el misterio más alto: la unidad eterna del Padre, del Hijo y del Espíritu, esa comunión viva que Ireneo descifra y que el Concilio de Nicea proclama para siempre.

Un solo Dios, tres personas:

la unidad más perfecta, el amor más perfecto, la libertad más perfecta.

Pero mientras el cielo se abría, la tierra seguía —y sigue— levantando ídolos.

El laicismo moderno, creyéndose liberado de la religión, inauguró otro tipo de paganismo: dinero, éxito, cuerpo, prestigio, poder, autoimagen, productividad, consumo. Y ahora, en un giro nuevo, la fascinación por lo tecnológico: máquinas, pantallas, algoritmos, inteligencias artificiales. La criatura se inclina ante lo que fabrica, como si buscara en su obra una trascendencia que solo el Creador puede dar.

No hace falta creer en dioses antiguos para vivir de rodillas:

basta con entregarle el corazón a lo que no puede sostenerlo.

La idolatría es psicológica antes que teológica: nace de un miedo.

Miedo a la soledad, a la falta de valor, al fracaso, al abandono.

Ningún ídolo existe sin una herida que lo sostiene.

Por eso no se destruyen con golpes; se desmontan con verdad.

El primer paso es reconocer la herida.

El segundo, distinguir qué acompaña y qué esclaviza.

El tercero, aprender a esperar sin fabricar dioses de emergencia.

El cuarto, abrirse a la presencia que no siempre se siente, pero siempre sostiene.

Desmontar un ídolo es dejar que Cristo ocupe el espacio que le pertenece.

No para imponer, sino para liberar.

No para exigir, sino para sanar.

No para suplantar la humanidad, sino para llenarla de luz.

La cultura actual nos empuja hacia la saturación: demasiados estímulos, demasiadas voces, demasiadas imágenes. Y sin embargo, en esa saturación, el alma siente más que nunca la sequedad. Somos un pueblo que camina por un desierto lleno de espejismos. Desde afuera parece abundancia; desde adentro es sed.

Pero el desierto no es un castigo.

Es el lugar donde vuelve a resonar la palabra esencial:

“Yo soy.”

Volver al Dios único y trinitario es regresar al centro del alma, donde ninguna imagen puede ocupar su lugar. Es respirar sin miedo en un mundo que pide adoración constante. Es redescubrir la libertad de quien ya no necesita idolatrar nada, porque sabe que es amado desde dentro. Es contemplar el mundo sin arrodillarse ante él.

Cuando las imágenes caen, queda la Presencia.

Cuando los ídolos se desvanecen, aparece la verdad.

Cuando el corazón vuelve al único Dios, vuelve también a sí mismo.

Y así, una vez más, el mandamiento se vuelve llamada, no imposición:

“Escucha, Israel… el Señor es Uno.”

Ese Uno es amor, y ese amor es la única adoración que libera.

RETURNING TO THE GOD WHO CALLS US BY NAME

The first commandment did not descend as a cold prohibition but as a compass for the heart:

“Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One.”

Before it was law, it was identity —a voice reminding us who we are and where life turns. And yet, from the moment that voice sounded, humanity has carried the constant temptation to build idols, even when we consider ourselves too modern, too rational, too iconoclastic to fall into such things.

But the truth is simpler and more painful: we do not know how to live without worshipping something.

The story of the golden calf reveals this with unsettling clarity. Moses climbs the mountain to meet God, and the people below, feeling abandoned, grow anxious. They cannot bear the waiting. They cannot tolerate the silence. And so they do what the human heart always does when it loses its center: they make a visible god. Not out of malice, but out of fear. Not out of rebellion, but out of desperation.

The golden calf is a mirror.

It does not show a primitive people; it shows the structure of the human soul.

When faith weakens, we replace it.

When God is silent, we invent substitutes.

When we cannot see, we fabricate an image.

When we cannot feel, we bow to whatever shines.

Idolatry never disappears; it simply adapts.

Then come forty years in the desert, a long purification. It was not punishment but formation: learning to live without clinging to what can be touched, seen, or controlled. Learning to trust the God who feeds from nothing and speaks from silence.

And in the fullness of time, something greater happens: God becomes flesh.

With Christ, the One draws near, becomes visible, becomes touchable, and reveals that the eternal unity proclaimed in the Shema contains a mystery deeper than we imagined: the communion of Father, Son, and Spirit. Irenaeus discerns it; Nicea proclaims it.

But while heaven opened, the earth kept producing idols.

Modern secularism, believing itself free of religion, ended up creating a new paganism: money, success, the body, prestige, power, productivity, consumption. And now, a new fascination arises: technology as a kind of human-made transcendence. Artificial intelligence as a mirror of human desire for omnipotence. Prometheus with a touchscreen.

One does not need ancient gods to kneel.

One only needs to give the heart to something that cannot hold it.

Idolatry is psychological before it is theological.

It is born from fear —fear of loneliness, of failure, of insignificance, of abandonment.

Every idol stands on a wound.

Thus, idols are not smashed from the outside; they are dissolved from the inside.

The first step is to recognize the wound.

The second, to discern what accompanies and what enslaves.

The third, to learn to wait without fabricating emergency gods.

The fourth, to open oneself to a Presence that does not always feel close but never ceases to sustain.

Dismantling an idol is allowing Christ to inhabit the place that has always been His.

Not to impose, but to free.

Not to demand, but to heal.

Not to shrink humanity, but to fill it with light.

Our culture saturates us with images, voices, distractions. And yet, in the middle of that saturation, the soul feels a deeper dryness than ever. We are a people wandering a desert full of mirages. From the outside it looks like abundance; from within, it is thirst.

But the desert is not a punishment.

It is the place where the essential word sounds again:

“I AM.”

To return to the one and triune God is to return to the center of the soul, where no image can take His place. It is breathing freely in a world that constantly demands devotion. It is rediscovering the freedom of a heart that no longer needs idols because it knows it is loved from within. It is learning to look at the world without bowing before it.

When images fall, Presence remains.

When idols vanish, truth appears.

When the heart returns to the One, it returns to itself.

And so the commandment becomes invitation, not imposition:

“Hear, O Israel… the Lord is One.”

That One is love, and that love is the only worship that liberates.

conocimiento humano a la mente divina

Israel Centeno

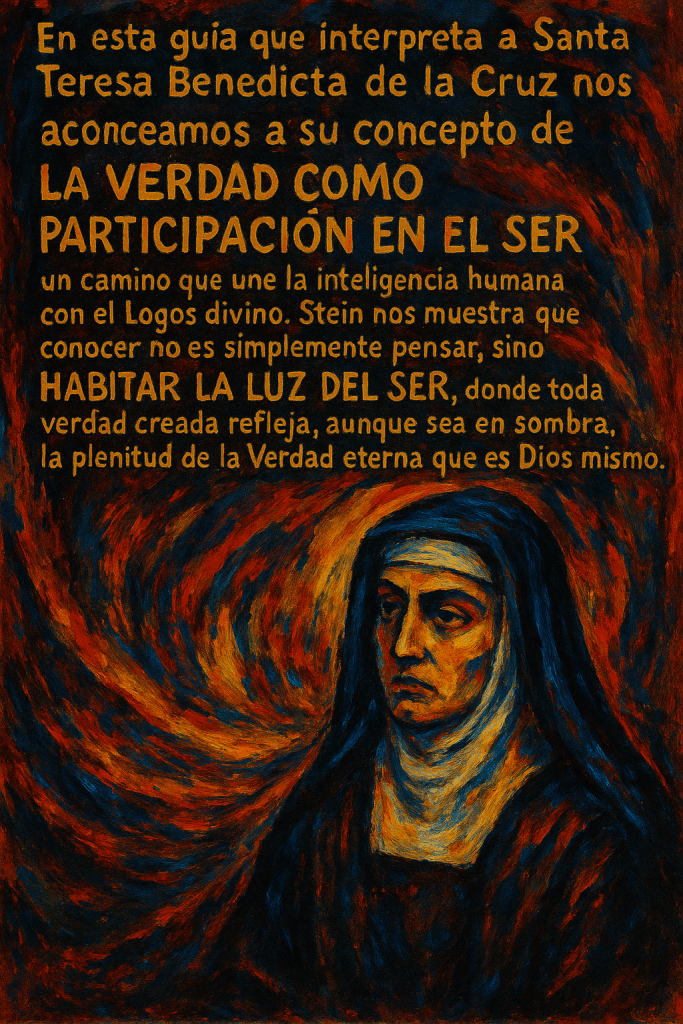

Interpretando a Santa Teresa Benedicta de la Cruz

I. La verdad como acontecimiento del ser

La verdad, dice Edith Stein, sucede cuando una mente conoce un ente. No es una sustancia ni un objeto, sino una relación viva entre el ser y la inteligencia. En la tradición aristotélico-tomista, se define como adaequatio rei et intellectus (la adecuación del intelecto con la cosa). Pero Stein va más allá: muestra que toda verdad está enraizada en la estructura misma del Ser y, en última instancia, en el Logos divino que sostiene la existencia.

II. La mente infinita y la mente finita

En la Mente divina —el ser absoluto— no hay distinción entre conocer y ser. Dios es la verdad porque en Él el ser y el conocer coinciden plenamente. Por eso el Logos puede decir: “Yo soy la Verdad.” En Dios, toda criatura es conocida antes de existir; su verdad precede a su aparición temporal. La verdad es eterna porque participa del conocimiento eterno de Dios.

La mente humana, en cambio, conoce en el tiempo, paso a paso. Para nosotros, la verdad es a la vez meta y camino: el resultado del proceso de conocer. El alma no posee la verdad, la busca y la habita parcialmente. Solo Dios la posee en plenitud.

III. Verdades creadas y lenguaje

Santo Tomás habla de la veritas creata, la “verdad creada”: las verdades particulares que surgen cuando el intelecto humano formula juicios sobre el mundo. Cada proposición verdadera es un reflejo finito de la mente divina.

Stein explica que cuando decimos “la rosa es roja”, el juicio concluye un proceso de conocimiento. El intelecto ha unido la esencia (quidditas) con su existencia concreta (haecceitas). El lenguaje no es solo expresión: es el lugar donde la mente humana reproduce en miniatura la estructura del Logos. Por eso las proposiciones verdaderas tienen una “existencia ideal” anterior a su formulación: el mundo es cognoscible porque ya está pensado en Dios.

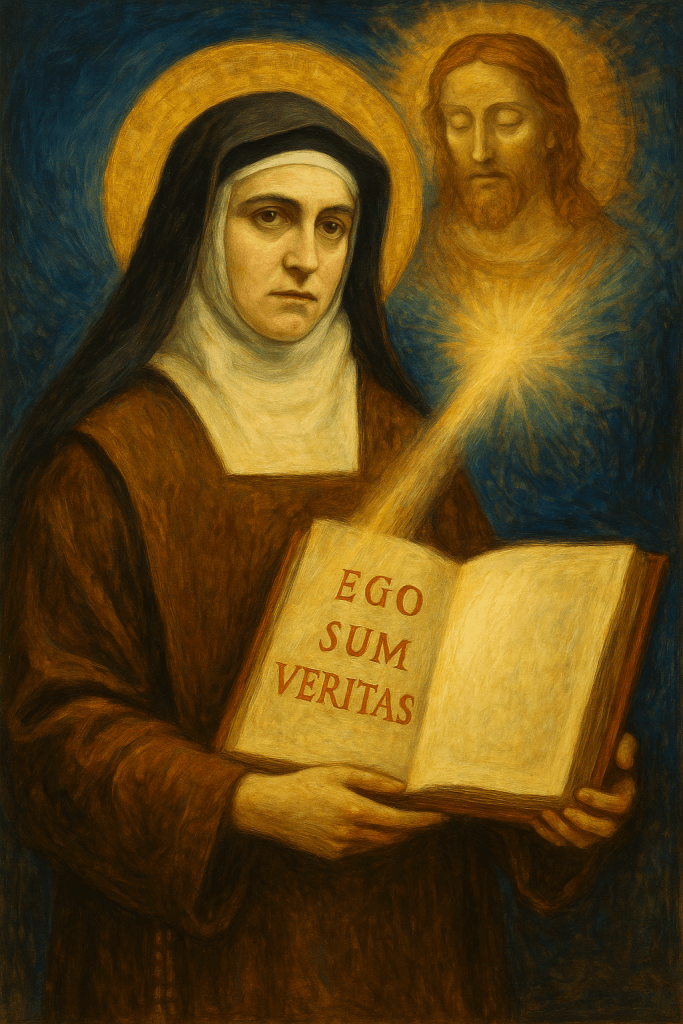

IV. El Logos encarnado: la verdad hecha carne

Cuando Stein pasa de la filosofía a la teología, identifica la plenitud de la verdad con la Encarnación. El Logos eterno —la Palabra de Dios— no solo crea, sino que entra en la creación. En Cristo, el conocimiento divino y la realidad humana se hacen uno. El Verbo encarnado es la forma visible de la Verdad eterna: Dios conoce a la humanidad desde dentro.

El conocimiento humano, herido por la fragmentación y la duda, es redimido en Cristo. Ya no conoce desde la distancia, sino desde la comunión. La Encarnación convierte el conocer en un acto de amor: conocer es participar del Ser que se entrega.

V. La luz del conocimiento

El prólogo del Evangelio de Juan ilumina toda esta ontología: “En Él estaba la vida, y la vida era la luz de los hombres.” Esa luz es la inteligencia divina que sostiene todo conocimiento humano. Cada vez que el alma comprende una verdad, participa —aunque sea mínimamente— en la luz del Logos. Por eso el acto de conocer tiene una estructura trinitaria:

VI. La verdad como comunión y redención

Para Stein, la verdad no se opone a la fe, sino que halla en ella su plenitud. La fe es el conocimiento más alto porque es conocimiento por unión. En la cruz, el Logos encarnado lleva la verdad a su límite: enfrenta la falsedad, el dolor y la muerte, y los transforma en revelación. Así, el conocimiento humano es redimido: puede ver sentido incluso en el sufrimiento.

El conocer deja de ser conquista: se vuelve contemplación. La verdad ya no se busca como posesión, sino como morada.

VII. Conclusión: habitar la verdad

En la síntesis de Edith Stein, la verdad no es una fórmula lógica, sino un modo de ser. Ser verdadero es existir en relación con el Logos. Toda criatura participa de la Verdad en la medida en que participa del Ser. El impulso de conocer no es mera curiosidad: es nostalgia del origen.

Por eso el alma que conoce con amor participa en el mismo acto por el cual Dios conoce y ama al mundo. La verdad no se posee: se habita. Y en esa morada se cumple la palabra definitiva del Logos: “Yo soy la Verdad.”

I. El ser real y el ser actual

Cuando Stein habla de “ser actual” (aktuell), no se refiere al punto culminante del ser, sino a su realidad efectiva, al hecho de existir realmente en el tiempo. Toma como ejemplo una rosa: su color rojo, su fragancia y su forma son propiedades esenciales que la constituyen. Aunque la flor se marchite o pierda su aroma, sigue siendo la misma rosa, porque su realidad no depende de conservar la plenitud de sus propiedades, sino de la continuidad de su sustancia.

La rosa en capullo aún no es plenamente “real”: está en potencia. Y cuando se seca y pierde sus hojas, deja de ser. Por eso, el ser finito nunca es plenamente actual en toda su posibilidad de ser; siempre permanece parcialmente potencial. En cada momento de su existencia, algo en él aún no se ha desplegado, o ya ha comenzado a desaparecer.

El ser finito, para Stein, vive en la tensión entre lo que es y lo que puede llegar a ser.

II. El ser ideal y las especies

Aquí introduce el concepto de ser ideal. Cuando hablamos del color rojo de la rosa, podemos entenderlo no solo como propiedad de una flor concreta, sino como especie ideal de “rojo brillante”, que puede repetirse en otras rosas o en otros objetos. Esta posibilidad de actualizarse en distintos individuos pertenece a la naturaleza del ser ideal.

El ser ideal no depende de la materia ni de un individuo particular; su posibilidad reposa en sí mismo, no en las cosas. Es el ámbito de las formas puras: colores, sonidos, figuras geométricas, que existen fuera del tiempo y del cambio.

El ser ideal está más cerca del ser puro que el ser de las cosas, porque no fluye ni se degrada: permanece. Stein reconoce aquí la intuición platónica —el “mundo de las ideas” como más real que el sensible—, pero no acepta que esas ideas sean “rígidas y muertas”. Redefine la actualidad (Aktualität) no solo como existencia o plenitud, sino también como eficacia y acción (Wirksamkeit). Las ideas, entonces, no son modelos estáticos: son formas activas que operan en la génesis de las cosas.

III. El vínculo entre el ser ideal, el ser divino y el ser de las cosas

Stein distingue tres modos de ser:

IV. Individuación: materia y forma

Stein retoma la pregunta clásica de Aristóteles y Santo Tomás: ¿qué hace que una cosa sea este individuo y no otro? La respuesta tradicional es que la materia (materia signata quantitate) es el principio de individuación. Pero Stein se pregunta si esto siempre se cumple: ¿hay seres individuales cuya identidad no dependa de la materia? (Ejemplo: almas, ángeles, formas puras.)

En los seres materiales, la materia da “plenitud y peso” al ser; pero no puede explicar la existencia por sí sola, pues es solo potencia. La forma —la especie o essentia— da estructura, pero tampoco basta: sin materia, sería solo posibilidad vacía. Por tanto, el ser real resulta del todo: materia configurada por la especie y por la forma individual.

La cosa concreta no es solo “una especie + materia”, sino una unidad irreductible, con una plenitud que no puede descomponerse.

V. El artista y el modelo

Stein usa una analogía artística: cuando un escultor modela en mármol la figura de un joven, la obra final —la estatua— es el individuo concreto. El artista tenía previamente una “idea” en mente: esa idea corresponde a la especie o forma esencial de lo que la escultura será. La materia (el mármol) recibe forma según ese modelo.

Del mismo modo, Dios es el artista creador. Las ideas —los arquetipos de las cosas— están en su mente, y el mundo es su realización en la materia. Por eso, dice Santo Tomás, la verdad puede llamarse “creada”: antes de existir, la cosa solo “es” en la mente divina, no como criatura, sino como esencia creadora.

VI. Interpretación final

Este fragmento de Stein describe un sistema ontológico trinitario del ser:

Síntesis interpretativa

Edith Stein sintetiza en este fragmento tres tradiciones:

Interpreting Saint Teresa Benedicta of Jesus

From Human Knowledge to the Divine Mind

Truth, says Edith Stein, happens when a mind knows a being. It is not a substance or an object, but a living relationship between being and intelligence. In the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition, it is defined as adaequatio rei et intellectus (the adequacy of the intellect to the thing). But Stein goes further: she shows that all truth is rooted in the structure of Being itself and, ultimately, in the divine Logos that sustains existence.

In the Divine Mind—the absolute being—there is no distinction between knowing and being. God is the truth because in God, being and knowledge fully coincide. That is why the Logos can say: “I am the Truth.” In God, every creature is known before it exists; its truth precedes its temporal appearance. Truth is eternal because it participates in God’s eternal knowledge.

The human mind, on the other hand, knows in time, step by step. For us, truth is both goal and path: the result of the process of knowing. The soul does not possess the truth, but seeks and inhabits it partially. Only God possesses it in fullness.

Saint Thomas speaks of veritas creata, “created truth”: the particular truths that arise when the human intellect makes judgments about the world. Each true proposition is a finite reflection of the divine mind.

Stein explains that when we say “the rose is red,” the judgment concludes a process of knowledge. The intellect has united the essence (quidditas) with its concrete existence (haecceitas). Language is not just expression: it is the place where the human mind reproduces in miniature the structure of the Logos. That is why true propositions have an “ideal existence” prior to their formulation: the world is knowable because it is already thought in God.

When Stein moves from philosophy to theology, she identifies the fullness of truth with the Incarnation. The eternal Logos—the Word of God—not only creates, but enters creation. In Christ, divine knowledge and human reality become one. The incarnate Word is the visible form of eternal Truth: God knows humanity from within.

Human knowledge, wounded by fragmentation and doubt, is redeemed in Christ. It no longer knows from a distance, but from communion. The Incarnation turns knowing into an act of love: to know is to participate in the Being that gives itself.

The prologue of the Gospel of John illuminates this entire ontology: “In Him was life, and the life was the light of men.” That light is the divine intelligence that sustains all human knowledge. Each time the soul understands a truth, it participates—even minimally—in the light of the Logos. That is why the act of knowing has a Trinitarian structure:

– The I who knows (image of the Son),

– The created object (work of the Father),

– And the light of understanding (action of the Spirit).

To know, then, is a mode of communion with the Trinity. True thought does not separate: it unites.

For Stein, truth is not opposed to faith, but finds its consummation in it. Faith is the highest knowledge because it is knowledge by union. On the cross, the incarnate Logos brings truth to its limit: faces falsehood, pain, and death, and transforms them into revelation. Human knowledge is thus redeemed: it can see meaning even in suffering.

Knowing ceases to be conquest: it becomes contemplation. Truth is no longer sought as possession, but as dwelling.

In Edith Stein’s synthesis, truth is not a logical formula, but a way of being. To be true is to exist in relation to the Logos. Every creature participates in Truth to the extent that it participates in Being. The impulse to know is not mere curiosity: it is nostalgia for the origin.

That is why the soul that knows with love participates in the very act by which God knows and loves the world. Truth is not possessed: it is inhabited. And in that dwelling, the definitive word of the Logos is fulfilled: “I am the Truth.”

When Stein speaks of “actual being” (aktuell), she does not refer to the culminating point of being, but to its effective reality, to the fact of really existing in time. She takes as an example a rose: its red color, its fragrance, its form are essential properties that constitute it. Even if the flower withers or loses its aroma, it is still the same rose, for its reality does not depend on maintaining the fullness of its properties, but on the continuity of its substance.

The rose in bud is not yet fully “real”: it is in potency. And when it dries and loses its leaves, it ceases to be. Hence, finite being is never fully actual in all its possibility of being; it always remains partially potential. At every moment of its existence, something in it has not yet been unfolded, or has already begun to disappear.

Finite being, for Stein, lives in the tension between what it is and what it can become.

Here she introduces the concept of ideal being. When we speak of the red color of the rose, we can understand it not only as a property of a concrete flower, but as an ideal species of “brilliant red,” which could be repeated in other roses or other objects. This possibility of being actualized in different individuals belongs to the nature of ideal being.

Ideal being does not depend on matter or a particular individual; its possibility rests in itself, not in things. It is the realm of pure forms: colors, sounds, geometric figures, which exist outside time and change.

Ideal being is closer to pure being than the being of things, because it does not flow or degrade: it remains. Stein recognizes here the Platonic intuition—the “world of ideas” as more real than the sensible world—but does not accept that these ideas are “rigid and dead.” She redefines actuality (Aktualität) not only as existence or fullness, but also as efficacy and action (Wirksamkeit). Ideas, then, are not mere static models: they are active forms that operate in the genesis of things.

Stein distinguishes three modes of being:

– Divine being—Actus Purus—which is absolute fullness, without potentiality.

– The being of things, where reality and potentiality coexist.

– Ideal being, which participates in pure being, but without fullness: it possesses an “unfulfilled possibility.”

Ideas or species are the bridge between God and creation. They do not exist independently, as in Plato, but in the divine mind, where they are “eternal types” according to which things are formed. Thus, when a rose exists, it participates in its ideal species—the “roseness”—but that species is not outside God, but in his creative mind.

Stein takes up the classic question of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas: what makes a thing this individual and not another? The traditional answer is that matter (materia signata quantitate) is the principle of individuation. But Stein asks if this always holds: are there individual beings whose identity does not depend on matter? (Example: souls, angels, pure forms.)

In material beings, matter provides the “fullness and weight” of being; but it cannot explain existence by itself, for it is only potency. Form—the species or essentia—gives structure, but is not enough: without matter, it would be only empty possibility. Therefore, real being results from the whole: matter configured by the species and by the individual form.

The concrete thing is not just “a species + matter,” but an irreducible unity, with a fullness that cannot be decomposed.

Stein uses an artistic analogy: when a sculptor models in marble the figure of a youth, the final work—the statue—is the concrete individual. The artist previously had an “idea” in mind: that idea corresponds to the species or essential form of what the sculpture will be. The matter (the marble) receives form according to that model.

Similarly, God is the creative artist. The ideas—the archetypes of things—are in his mind, and the world is their realization in matter. That is why, says Thomas, truth can be called “created”: before existing, the thing only “is” in the divine mind, not as a creature, but as a creative essence.

This fragment of Stein describes a Trinitarian ontological system of being:

– Divine being—pure act, source of all.

– Ideal being—the eternal forms in the divine mind.

– Real being—finite things that participate in those forms in time.

Matter and form, potency and act, idea and realization, are modes of participation in the one absolute Being. The world is not a mere copy of ideas, but an act of communication of the divine Being. Each thing, by existing, “imitates” the creative Word, which is its archetype and cause.

Thus, when Thomas says that ideas are in God, not outside Him, Stein sees her Christological vision confirmed: the Logos is not an abstract intermediary, but the very act of creation—the living form of being.

Edith Stein synthesizes in this fragment three traditions:

– Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas: act and potency, matter and form, composite being.

– Plato: ideas as eternal types.

– Phenomenology: the experience of being as a gift of meaning to the subject.

The result is a dynamic metaphysics: ideal being is not separate, but active in the becoming of the world. The creator is at once artist and model, cause and archetype. Every creature—like the rose—is a temporal expression of an eternal form that lives in the divine mind.

The human being, in knowing, participates in that same creative dynamism: when one knows a truth, one realizes an ideal form in the intellect, and thus imitates the divine act of knowledge.´

From Human Knowledge to the Divine Mind

Israel Centeno

Truth, says Edith Stein, occurs when a mind encounters a being.

It is not a substance but a living relation between being and intelligence.

In the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition, truth is defined as the adaequatio rei et intellectus—the correspondence of intellect and thing.

Stein, however, goes further: she roots truth in the structure of Being itself, and ultimately, in the divine Logos that sustains all existence.

In the divine Mind—the absolute Being—there is no distinction between knowing and being.

God is truth because in Him being and knowing coincide perfectly.

Hence the Logos can say: “I am the Truth.”

In God, every creature is known before it exists; its truth precedes its temporal appearance.

Truth is eternal because it participates in God’s eternal knowledge.

The human mind, by contrast, knows in time, step by step.

Truth, for us, is both goal and path—the result of the act of knowing.

The soul does not possess truth; it dwells in it incompletely.

Only God possesses it in fullness.

St. Thomas speaks of veritas creata—“created truth”:

the finite truths born when the human intellect formulates judgments about the world.

Each true proposition is a finite reflection of the divine Mind.

When we say “the rose is red,” the act of judgment concludes the process of knowing.

The intellect unites essence (quidditas) and existence (haecceitas).

Language becomes the place where the human mind recreates in miniature the structure of the Logos.

Thus, true propositions have an “ideal existence” even before we think them:

the world is knowable because it is already thought in God.

When Stein moves from philosophy to theology, she identifies the fullness of truth with the Incarnation.

The eternal Logos—the Word of God—does not only create; He enters creation.

In Christ, divine knowledge and human reality become one.

The Incarnate Word is the visible form of eternal Truth:

God knowing man from within.

Human knowledge, wounded by fragmentation and doubt, is redeemed in Christ.

It no longer knows from distance but from communion.

The Incarnation turns knowledge into an act of love:

to know is to participate in Being as gift.

The prologue of John’s Gospel illuminates this entire ontology:

“In Him was life, and the life was the light of men.”

That light is the divine intelligence sustaining all human understanding.

Each time the soul perceives a truth, it participates—however slightly—in the eternal act by which the Logos knows the Father.

Hence the act of knowing has a Trinitarian structure:

To know, then, is a form of communion with the Trinity.

True thought does not divide: it unites.

For Stein, truth does not oppose faith; it reaches its fulfillment in it.

Faith is the highest form of knowledge because it is knowledge through union.

On the cross, the incarnate Logos pushes truth to its limit: He confronts falsehood, pain, and death, transforming them into revelation.

Human knowing is thus redeemed—it can now perceive meaning even in suffering.

Knowledge ceases to be conquest; it becomes contemplation.

Truth is no longer something to possess, but something to inhabit.

In Stein’s synthesis, truth is not a logical property but a mode of being.

To be true is to exist in relation to the Logos.

Every creature participates in truth to the extent that it participates in being.

The human drive to know is not mere curiosity—it is nostalgia for its origin.

Thus, the soul that knows through love participates in the very act by which God knows and loves the world.

Truth is not possessed: it is inhabited.

And in that dwelling, the definitive word of the Logos is fulfilled:

“I am the Truth.”

Del conocimiento humano a la mente divina

La verdad —dice Edith Stein— sucede cuando una mente conoce un ser.

No es una sustancia ni un objeto, sino una relación viva entre el ser y la inteligencia.

En la tradición aristotélico-tomista, se la define como adaequatio rei et intellectus (la adecuación del intelecto a la cosa).

Pero Stein va más allá: muestra que toda verdad se enraíza en la estructura del Ser mismo y, en última instancia, en el Logos divino que sostiene la existencia.

En la Mente divina —el ser absoluto— no hay distinción entre conocer y ser.

Dios es la verdad porque en Él el ser y el conocimiento coinciden plenamente.

Por eso el Logos puede decir: “Yo soy la Verdad.”

En Dios, cada criatura es conocida antes de existir; su verdad precede a su aparición temporal.

La verdad es eterna porque participa del conocimiento eterno de Dios.

La mente humana, en cambio, conoce en el tiempo, paso a paso.

La verdad, para nosotros, es meta y camino: el resultado del proceso de conocer.

El alma no posee la verdad, sino que la busca y la habita parcialmente.

Solo Dios la posee en plenitud.

Santo Tomás habla de veritas creata, “verdad creada”:

las verdades particulares que surgen cuando el intelecto humano formula juicios sobre el mundo.

Cada proposición verdadera es un reflejo finito de la mente divina.

Stein explica que cuando decimos “la rosa es roja”, el juicio concluye un proceso de conocimiento.

El intelecto ha unido la esencia (quidditas) con su existencia concreta (haecceitas).

El lenguaje no es solo expresión: es el lugar donde la mente humana reproduce en pequeño la estructura del Logos.

Por eso las proposiciones verdaderas tienen una “existencia ideal” anterior a su formulación:

el mundo es cognoscible porque está ya pensado en Dios.

Cuando Stein pasa de la filosofía a la teología, identifica la plenitud de la verdad con la Encarnación.

El Logos eterno —la Palabra de Dios— no solo crea, sino que entra en la creación.

En Cristo, el conocimiento divino y la realidad humana se hacen uno.

El Verbo encarnado es la forma visible de la Verdad eterna:

Dios conoce al hombre desde dentro.

El conocimiento humano, herido por la fragmentación y la duda, es redimido en Cristo.

Ya no conoce desde la distancia, sino desde la comunión.

La Encarnación convierte el conocer en un acto de amor:

conocer es participar en el Ser que se dona.

El prólogo del Evangelio de Juan ilumina toda esta ontología:

“En Él estaba la vida, y la vida era la luz de los hombres.”

Esa luz es la inteligencia divina que sostiene todo conocimiento humano.

Cada vez que el alma comprende una verdad, participa —aunque sea mínimamente— de la luz del Logos.

Por eso el acto de conocer tiene una estructura trinitaria:

Conocer, entonces, es un modo de comunión con la Trinidad.

El pensamiento verdadero no separa: une.

Para Stein, la verdad no se opone a la fe, sino que encuentra en ella su consumación.

La fe es el conocimiento más alto porque es conocimiento por unión.

En la cruz, el Logos encarnado lleva la verdad al límite: enfrenta la mentira, el dolor y la muerte, y los transforma en revelación.

El conocimiento humano queda así redimido: puede ver el sentido incluso en el sufrimiento.

Conocer deja de ser conquista: se vuelve contemplación.

La verdad ya no se busca como posesión, sino como morada.

En la síntesis de Edith Stein, la verdad no es una fórmula lógica, sino un modo de ser.

Ser verdadero es existir en relación con el Logos.

Toda criatura participa de la Verdad en la medida en que participa del Ser.

El impulso de conocer no es simple curiosidad: es nostalgia del origen.

Por eso, el alma que conoce con amor participa del acto mismo por el cual Dios conoce y ama al mundo.

La verdad no se posee: se habita.

Y en esa morada se cumple la palabra definitiva del Logos:

“Yo soy la Verdad.”

Israel Centeno

1. La Ilustración coronó a la razón; olvidó que, sin Verdad, la razón sirve al deseo.

2. Sin Dios, la inteligencia legitima la voluntad, no la verdad.

3. El corazón tiene razones que la razón teme mirar.

4. Nos prometieron que matar a Dios traería la paz. Solo cambió el nombre del altar.

5. La Razón engendró el Terror; el Progreso, las trincheras; la Libertad, Hiroshima.

6. “Paz”, “orden”, “humanidad”: nuevos ídolos del sacrificio.

7. El mal sonríe más cuando se cree virtuoso.

8. Definir al hombre sin Dios es reducirlo a su sombra.

9. Darwin nos hizo bestias, Freud neuróticos, Marx engranajes.

10. Negar el original para entender la imagen: locura del siglo.

11. La Ilustración: el más brillante suicidio del espíritu.

12. Ícaro no cayó por volar, sino por olvidar a quién volaba.

13. Creer que el hombre creó a Dios: la fe más crédula del incrédulo.

14. Antes de Nietzsche, nadie pensó que Dios era un invento; ahora lo creemos dogma.

15. La modernidad: negar lo espiritual mientras se lo busca en píldoras y visiones.

16. El corazón, decía Pascal, conoce un orden que la razón no ve.

17. Cuando desterramos a Dios, comenzamos a adorar nuestras ruinas.

18. La razón, sin fe, no ilumina: calcula.

19. El hombre moderno adora la nada con fervor religioso.

20. La caída del hombre no fue del cielo: fue hacia adentro

Israel Ceenteno

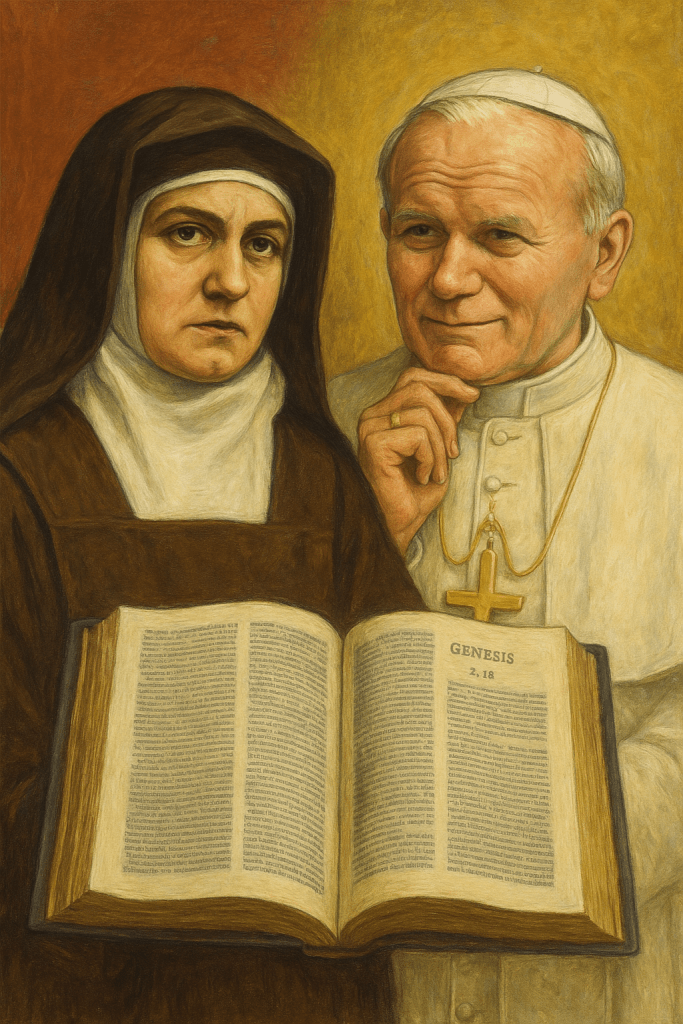

Edith Stein (Santa Teresa Benedicta de la Cruz, 1891–1942), filósofa fenomenóloga, teóloga y mártir, tuvo una influencia significativa, aunque indirecta, en las catequesis de Juan Pablo II sobre la Teología del Cuerpo (1979–1984). No se trata de una cita directa ni de una dependencia textual, sino de una convergencia profunda de espíritu y método. Ambos compartieron el mismo horizonte intelectual: la integración entre la fenomenología husserliana y el tomismo, síntesis que dio origen al llamado “tomismo de Lublin”, corriente a la que pertenecía Karol Wojtyła.

1. Contexto intelectual: la fenomenología tomista y la persona unificada

Wojtyła conoció las obras de Stein en las décadas de 1940 y 1950, atraído por su intento de unir la fenomenología —el análisis de la experiencia vivida— con la metafísica del ser de Santo Tomás de Aquino. Ambos comprendían a la persona como una unidad psico-física abierta a la trascendencia. Stein, discípula de Edmund Husserl, elaboró en Sobre el problema de la empatía (1917) y en los Ensayos sobre la mujer (1932) una antropología que afirma la unidad cuerpo-alma y el valor cognoscitivo de la empatía. Estas ideas resonaron en el pensamiento wojtyliano y contribuyeron a su búsqueda de una antropología integral capaz de articular libertad, afectividad y corporeidad.

No existió encuentro personal entre ambos —Stein murió en Auschwitz en 1942, cuando Wojtyła tenía 22 años—, pero sí una transmisión espiritual e intelectual a través de Roman Ingarden, amigo y colega de Stein, quien fue también maestro de Wojtyła.

2. Paralelismos en la Teología del Cuerpo

La Teología del Cuerpo es una antropología teológica que interpreta el cuerpo humano como lenguaje del amor divino. En ella confluyen fenomenología, revelación y tomismo. La influencia de Stein se advierte en tres núcleos fundamentales:

a) Unidad alma-cuerpo y dignidad personal.

Stein rechaza el dualismo cartesiano y propone que el cuerpo pertenece a la esencia de la persona. Wojtyła prolonga esta intuición al afirmar que el cuerpo es “teología visible”, signo sacramental del amor divino. El cuerpo humano, con su masculinidad y feminidad, manifiesta la comunión trinitaria.

b) Visión de la mujer y el “femenino”.

En sus ensayos sobre la mujer, Stein formula una “teología del femenino” basada en la empatía y la disposición interior como modos de amar y de donar. Wojtyła desarrolla esa intuición en Mulieris Dignitatem (1988), donde presenta la “genialidad femenina” como don de acogida y cooperación con el amor creador.

c) Personalismo y ethos del don.

Para ambos, la persona es irreductible y el cuerpo es su medio de donación. Stein concibe la empatía como apertura al otro; Wojtyła la convierte en la dinámica del don de sí, fundamento de su ética personalista. El amor, para ambos, es la forma más alta de conocimiento y la realización plena del ser humano.

3. Lectura del Génesis y la complementariedad de los sexos: Stein, Wojtyła y la herencia platónica

Tanto Stein como Wojtyła comparten una lectura del Génesis que interpreta la diferencia sexual como reciprocidad originaria. “No es bueno que el hombre esté solo” (Gn 2,18) expresa una verdad ontológica: el ser humano está hecho para la comunión. Stein ve en la dualidad varón–mujer dos modos complementarios de ser persona. Wojtyła lleva esta intuición a su concepto de “significado esponsalicio del cuerpo”, en el que la diferencia sexual es el lenguaje mismo del amor creador.

Esa antropología bíblica se enlaza, de manera implícita, con la tradición platónica. En el Banquete, Platón describe el eros como nostalgia de una unidad perdida. Stein y Wojtyła reinterpretan esa intuición desde la fe: el amor humano no busca una fusión, sino una comunión personal en libertad. El eros se transfigura en ágape; la diferencia se convierte en signo de una unidad superior, reflejo del amor trinitario.

4. Influencia personal y eclesial de Juan Pablo II

Wojtyła reconoció explícitamente el valor espiritual y filosófico de Edith Stein. La beatificó en 1987, la canonizó en 1998 y la proclamó patrona de Europa, subrayando su testimonio como “síntesis dramática de nuestro siglo”. En Fides et Ratio (1998) la citó como modelo de filósofa que une razón y fe. Su figura influyó en el “nuevo feminismo” impulsado por Juan Pablo II, que retoma la visión steiniana de la mujer como cooperadora de la gracia.

5. Conclusión: convergencia espiritual y legado

La influencia de Edith Stein en la Teología del Cuerpo es indirecta pero decisiva. Su pensamiento fenomenológico-tomista preparó el terreno para que Wojtyła pudiera articular una teología del cuerpo como sacramento del amor divino. Ambos ofrecieron una antropología de la comunión en la que el cuerpo no es límite, sino transparencia del espíritu.

Stein no creó la Teología del Cuerpo, pero fue una de sus raíces invisibles: su pensamiento permitió que Karol Wojtyła expresara en lenguaje teológico lo que ella había vislumbrado filosóficamente, que el cuerpo humano es el lugar donde la persona se ofrece, se revela y se hace transparente al misterio de Dios

Israel Centeno

“Solo el alma en silencio puede oír a Dios.” — Edith Stein

La modernidad y la posmodernidad, cada una a su modo, creyeron poder alcanzar el sentido último de la realidad. La primera confió en la razón como herramienta universal; la segunda, en la disolución del sentido como forma de libertad. Ambas, sin embargo, se detienen ante el mismo muro: el misterio. El pensamiento moderno, agotado en su racionalismo, y el posmoderno, disuelto en su ironía, terminan reconociendo que no pueden acceder, por experiencia propia, a aquello que trasciende las categorías de espacio, tiempo y finitud.

Este límite no es fracaso: es frontera. Allí donde la palabra ya no basta, donde el lenguaje se quiebra y el pensamiento no alcanza, comienza el silencio que revela. En ese borde, el alma comprende que solo puede acceder a lo eterno a través de la gracia. Y la gracia no es conquista: es don. Edith Stein lo entendió cuando llevó la fenomenología hasta el umbral del ser. Comprendió que, por más refinado que sea el método, la conciencia no puede franquear por sí misma la distancia que la separa del Acto Puro. Solo puede disponerse, prepararse, vaciarse para recibir.

Llegamos a un tiempo donde toda herramienta humana —la razón, la ciencia, la técnica— ha sido puesta al servicio de descifrar lo indecible. Pero, a medida que se multiplican los logros del conocimiento, crece la evidencia de que el alma sigue sedienta. Y el reto, hoy, no es ya comprender, sino abrirse. El pensamiento que vendrá no puede limitarse a rehacer los esquemas de la escolástica, ni quedarse en el nihilismo posmoderno. Debe ir más allá de ambos: retornar a la tradición contemplativa, al camino interior que recorrieron Teresa de Jesús, Juan de la Cruz y los grandes humildes de la fe.

La fenomenología nos ofrece un método para eso: el método del horizonte. Todo fenómeno se da dentro de un campo de sentido que siempre apunta más allá de sí mismo. El alma, cuando se abre a ese horizonte, descubre que lo que aparece no se agota en lo visible, sino que remite a lo invisible. Dios no es fenómeno; es el fundamento del aparecer. Y el diálogo entre el alma y el ser —ese diálogo que Husserl inició y Stein llevó al Carmelo— continúa en nosotros cada vez que callamos y dejamos que el ser se manifieste.

Wittgenstein, al final del Tractatus, no cerró el camino, sino que lo abrió:

“De lo que no se puede hablar, hay que callar.”

Los ateos y racionalistas tomaron esa frase como una negación del misterio. Pensaron que lo que no puede nombrarse no existe. Pero Wittgenstein señalaba, precisamente, lo contrario: que el lenguaje se detiene, no porque el ser desaparezca, sino porque lo desborda. El silencio que sigue a la última palabra no es vacío: es plenitud. Es el umbral de lo indecible.

La mística lo entendió siglos antes. Santa Teresa, en su lectura divina, enseña:

“Lee y calla.”

Porque el alma, después de leer y pensar, debe guardar silencio para que la Palabra hable desde dentro. El silencio contemplativo no es mutismo, sino disposición; es el espacio donde el Verbo puede encarnarse. Y ese mismo silencio, interpretado por la fenomenología, es la epoché última: la suspensión de todo juicio para que la verdad se dé sin mediación.

Los verdaderos conocedores de Dios no fueron filósofos, sino humildes. Francisco de Asís, Catalina de Siena, el Padre Pío, Conchita Cabrera de Armida… no necesitaron teorías para encontrarse con Él. La razón construye torres; la humildad abre cielos. El conocimiento humano busca controlar; la sabiduría divina se recibe. Por eso el Evangelio dice:

“Quien se ensalza será humillado, y quien se humilla será ensalzado.”

El alma que se despoja, que se hace pobre de espíritu, se vuelve transparente a la luz de Dios.

La pobreza de espíritu no es ignorancia ni renuncia al pensamiento. Es liberación del ego cognitivo, el acto de descender de la soberbia de creer que el cerebro humano —encerrado en tres dimensiones, o cuatro si contamos el tiempo— puede comprender el misterio total del universo. Es aceptar que toda sabiduría verdadera comienza donde la mente se rinde. Solo el alma vacía puede ser llena de Dios.

La posmodernidad confundió el vacío con la nada, y el silencio con la ausencia. Pero ese mismo vacío, cuando se habita desde la fe, se convierte en morada del Ser. Allí, el alma reconoce que no es ella quien llega a Dios, sino Dios quien la toca. Y ese toque no depende del mérito, sino de la gracia. Es Él quien decide cuándo se concede la unión, cuándo se bautiza con fuego, cuándo el corazón humano y el corazón divino laten en un solo compás. Hasta entonces, nuestra tarea es callar, contemplar y dejar que el Amor hable.

El límite del pensamiento no es su fin, sino su cumplimiento. Allí donde la palabra se agota, comienza la adoración. El alma descansa en la Luz.

🇬🇧 Silence, Language, and Mystery

“Only the soul in silence can hear God.” — Edith Stein

Modernity and postmodernity, each in its own way, believed they could reach the ultimate meaning of reality. The first trusted reason as a universal tool; the second, the dissolution of meaning as freedom. Both, however, stop before the same wall: the mystery. Modern thought, exhausted by rationalism, and postmodern thought, dissolved in irony, both end up admitting that they cannot, by their own experience, reach that which transcends space, time, and finitude.

This limit is not failure; it is a threshold. Where words no longer suffice, where language breaks and thought cannot reach, silence begins—the silence that reveals. At that edge, the soul realizes it can only approach the eternal through grace. And grace is not conquest—it is gift. Edith Stein understood this when she carried phenomenology to the threshold of being. She saw that, no matter how refined the method, consciousness cannot, by itself, cross the distance that separates it from the Pure Act. It can only prepare, empty, and open itself to receive.

We have arrived at an age where every human tool—reason, science, technology—has been used to decipher the unsayable. Yet as knowledge multiplies, the soul remains thirsty. The challenge today is not to understand, but to open. The thought to come cannot merely rework scholastic frameworks or rest in postmodern nihilism. It must go beyond both: return to the contemplative tradition, the interior path once walked by Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, and the great humble ones of faith.

Phenomenology offers a way: the method of the horizon. Every phenomenon appears within a field of meaning that always points beyond itself. When the soul opens to that horizon, it discovers that what appears does not end in what is visible, but refers to what is invisible. God is not a phenomenon; He is the foundation of appearing. The dialogue between soul and being—the dialogue Husserl began and Stein carried into Carmel—continues in us each time we fall silent and let being manifest itself.

At the end of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein did not close the path; he opened it:

“What we cannot speak about, we must pass over in silence.”

Atheists and rationalists took that as a denial of mystery. They thought that what cannot be named does not exist. But Wittgenstein meant the opposite: language stops not because being vanishes, but because it overflows. The silence that follows the last word is not emptiness; it is fullness—the threshold of the unsayable.

The mystics understood this centuries earlier. Teresa of Ávila, in her lectio divina, teaches:

“Read, and be silent.”

Because the soul, after reading and thinking, must fall silent so that the Word may speak from within. Contemplative silence is not muteness; it is readiness—the space where the Word can take flesh. And this same silence, interpreted phenomenologically, is the ultimate epoché: the suspension of all judgment so that truth may reveal itself directly.

The true knowers of God were not philosophers but the humble: Francis of Assisi, Catherine of Siena, Padre Pio, Conchita Cabrera de Armida… they needed no theories to find Him. Reason builds towers; humility opens heavens. Human knowledge seeks to control; divine wisdom is received. That is why the Gospel says:

“Whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

The soul that strips itself bare, that becomes poor in spirit, becomes transparent to the light of God.

Poverty of spirit is not ignorance or rejection of thought. It is the liberation of the cognitive ego—the act of descending from the arrogance of believing that the human brain, bound to three dimensions (four, if we count time), can comprehend the full mystery of the universe. It is accepting that true wisdom begins where the mind surrenders. Only the empty soul can be filled with God.

Postmodernity confused emptiness with nothingness, and silence with absence. Yet that same emptiness, when inhabited by faith, becomes the dwelling of Being. There the soul realizes that it does not reach God; God reaches it. And that touch depends not on merit but on grace. It is He who decides when union is granted, when the heart is baptized with fire, when the human and divine hearts beat as one. Until then, our task is to be silent, to contemplate, and to let Love speak.

The limit of thought is not its end but its fulfillment. Where words fall silent, adoration begins. The soul rests in the Light.

Israel Centeno

🇪🇸 Dios y el acto puro:

“Solo el alma en silencio puede oír a Dios

Cuando Wittgenstein escribe al final del Tractatus “De lo que no se puede hablar, hay que callar”, no niega lo trascendente; señala su límite. Ese silencio no es vacío: es reverencia. No dice “Dios no existe”, sino “Dios no cabe en el lenguaje”. Lo indecible no desaparece: brilla en el límite de lo que puede decirse.

La fenomenología, al suspender toda valoración y prejuicio mediante la epoché, nos enseña a mirar sin categorías, a dejar que el ser se manifieste tal como es. Si aplicamos ese método a lo divino, descubrimos que el silencio wittgensteiniano no es negación, sino apertura. Callar no es renunciar a la palabra, sino prepararla. La epoché fenomenológica, en su forma más pura, se convierte en un ejercicio espiritual: una purificación del alma que, al abandonar el juicio y la interpretación, abre espacio a lo que se revela por sí mismo.

Así como Wittgenstein lleva el lenguaje a su límite, la fenomenología nos conduce al límite de la conciencia. Lo que el lenguaje no puede decir, la conciencia puede acoger en silencio. Allí donde la palabra termina, comienza la experiencia. Dios no es un objeto entre objetos, ni un fenómeno dentro del horizonte del mundo. No se da como algo de lo que podamos tener “experiencia” en sentido empírico. Pero sí se da como fundamento de todo darse, como fuente del aparecer. No se muestra como figura, sino como aquello que permite que algo aparezca.

Dios, entonces, no es fenómeno, pero todo fenómeno auténtico remite a Él. El ser finito, al mostrarse, revela su límite, y en ese límite brilla la infinitud. Fenomenológicamente, lo divino no se impone ni se prueba: se deja entrever. La conciencia que se descubre finita advierte que su ser no procede de sí misma. Esa conciencia, al encontrarse con su propia contingencia, toca el acto puro, no como contenido, sino como origen. El alma no ve a Dios: se siente mirada por Él.

El actus purus —el Ser que es solo acto, sin potencia ni cambio— no puede vivirse como experiencia directa. Y sin embargo, es vivenciable en el sentido más alto del término: no como percepción de algo, sino como participación en el ser mismo. Cuando el alma contempla sin juzgar, cuando cesa de constituir el mundo y simplemente acoge lo que se da, experimenta una evidencia silenciosa: la de no ser su propia fuente. En ese instante de claridad, el alma intuye el acto puro como presencia sin forma, como actualidad absoluta que sostiene todo lo que es.

Esa vivencia no ocurre en el discurso racional, sino en la contemplación. Y contemplar, en este contexto, no es pensar ni imaginar: es dejar que el ser se dé sin resistencia. Es el mismo movimiento del alma que describen Teresa de Jesús, San Juan de la Cruz y Edith Stein: cuando el yo se aquieta y el pensamiento se detiene, surge un lugar interior esquivo e infinito, un punto de contacto, un portal donde el alma trasciende el marco espacio-temporal y se abre a lo eterno. Allí no hay sujeto ni objeto, sino comunión. Ese punto, que parece pequeño, es infinitamente vasto, porque en él cabe Dios entero.

En ese espacio interior, Dios se hace semejante a nosotros y nosotros semejantes a Él. Las categorías humanas —sujeto, objeto, pensamiento, tiempo— se disuelven. El alma, liberada de su necesidad de comprender, se entrega. Y en esa entrega, el silencio de Wittgenstein se vuelve el silencio de la contemplación: no el mutismo del límite, sino el recogimiento de la presencia. El callar del filósofo se transforma en el callar del místico.

El acto puro no se “ve”: se reconoce en el ser sostenido. Es lo que hace posible que haya verdad, amor y existencia. La contemplación no es un modo de observar a Dios, sino el modo en que Dios nos deja participar de su propio acto de ser. El silencio final del Tractatus encuentra así su correspondencia en la oración contemplativa: la palabra que ya no nombra, porque se ha convertido en presencia.

Hablar de Dios desde la fenomenología es hablar desde el silencio. No es definir ni demostrar, sino dejar que lo que sostiene todo aparecer se revele en la conciencia abierta. Dios no puede categorizarse ni como sujeto ni como objeto, porque trasciende ambos: es la unidad absoluta donde conocer y ser se identifican. En Él, el acto puro es plenitud, y la contemplación es el modo humano de participar en esa plenitud.

Allí donde el tiempo se suspende, la conciencia deja de preguntar y se vuelve adoración. El alma descansa en la Luz.

🇬🇧 God and the Pure Act:

“Only the soul in silence can hear God.” — Edith Stein

When Wittgenstein writes at the end of the Tractatus, “What we cannot speak about, we must pass over in silence,” he does not deny the transcendent; he marks its limit. That silence is not emptiness—it is reverence. He does not say “God does not exist,” but “God cannot fit within language.” The unsayable does not vanish; it shines at the boundary of what can be said.

Phenomenology, by suspending all valuation and prejudice through the epoché, teaches us to look without categories, to let being reveal itself as it is. Applied to the divine, this means that Wittgenstein’s silence is not negation but openness. To be silent is not to renounce speech, but to prepare it. The pure epoché becomes a spiritual exercise, a purification of the soul that, by abandoning judgment and interpretation, opens space for what reveals itself.

As Wittgenstein brings language to its boundary, phenomenology brings consciousness to its own. What cannot be said may still be received in silence. Where words end, experience begins. God is not an object among objects, nor a phenomenon within the horizon of the world. He does not “appear” as something of which we can have empirical experience. Yet He gives Himself as the foundation of all givenness, as the source of appearance itself. He is not a figure within the field of vision, but that which allows vision to occur.

God, then, is not a phenomenon, yet every authentic phenomenon points toward Him. Finite being, in showing itself, reveals its limit—and in that limit, infinity glimmers. Phenomenologically speaking, the divine is not imposed or proven; it lets itself be intuited. Consciousness, upon discovering its finitude, perceives that its being is not self-originating. In that discovery lies the first contact with the pure act—not as content, but as source. The soul does not see God; it feels itself seen.

The actus purus—the Being that is pure act, without potentiality or change—cannot be experienced directly. Yet it can be lived, not as perception of something, but as participation in Being itself. When the soul contemplates without judgment, when it ceases to constitute the world and simply receives what is given, it experiences a silent evidence: that it is not its own source. In that clarity, the soul intuits the pure act as formless presence, as the absolute actuality sustaining all that is.

Such experience does not occur in rational discourse but in contemplation. To contemplate here is not to think or imagine; it is to let being give itself without resistance. It is the movement described by Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, and Edith Stein: when the self grows still and thought ceases, there emerges an inner space—elusive, infinite—a point of contact, a portal through which the soul transcends the frame of space and time and opens to the eternal. There is no subject or object there, only communion. That point, which seems so small, is infinitely vast, for it contains the fullness of God.

In that interior space, God becomes like us, and we become like God. Human categories—subject, object, thought, time—dissolve. The soul, freed from its need to understand, yields. And in that yielding, Wittgenstein’s silence becomes the silence of contemplation: not the muteness of limit, but the stillness of presence. The philosopher’s silence becomes the mystic’s silence.

The pure act cannot be “seen”; it can only be recognized in the being sustained. It is what makes truth, love, and existence possible. Contemplation is not a way of observing God, but the way God allows us to share in His own act of being. The final silence of the Tractatus thus finds its correspondence in contemplative prayer: a word that no longer names, because it has become presence.

To speak of God phenomenologically is to speak from silence—not to define or prove, but to let what sustains all appearance reveal itself in open consciousness. God cannot be categorized as subject or object, for He transcends both: He is the absolute unity where knowing and being are one. In Him, pure act is fullness, and contemplation is our way of participating in that fullness.

Where time is suspended, consciousness ceases to question and becomes adoration. The soul rests in the Light.

Israel Centeno

El universo no se sostiene en la materia,

sino en la relación.

Entre cada núcleo y su partícula orbitante

se extiende un abismo —

un silencio tan vasto

que disuelve toda idea de solidez.

Estamos hechos de distancia.

Compuestos de fuerzas que nunca se tocan,

y, sin embargo, lo sostienen todo.

Gravedad, magnetismo,

la fuerza débil y la fuerza fuerte:

los cuatro pilares invisibles

que sustentan lo visible.

Un error menor que cero

bastaría para devolverlo todo a la nada.

Y, sin embargo,

permanece.

Las constantes permanecen.

¿Quién sostiene esa precisión?

¿Quién insufla coherencia al caos?

El físico lo llama simetría.

El místico lo llama Dios.

Estos poemas no hablan de la materia,

sino de lo que la une;

no del tiempo,

sino de lo que lo hace sagrado.

Habitan el espacio

entre la partícula y la onda,

entre Kronos y Kairos,

entre la existencia y el Ser.

En ese espacio,

solo el amor hace contacto.

ENTANGLEMENT

La materia no es sólida;

nadie se toca.

Solo el amor

hace contacto.

Túnel:

pasaje sin distancia,

tránsito de lo invisible.

Lo que fue, ya es.

Conciencia:

campo que no cesa,

onda que no viaja,

presencia

sin antes ni después.

Y Dios

restaura

lo que pasó.

Nada se roza;

todo se atrae y se repele,

campo en tensión,

presencia sin contacto.

Superposición

que solo el amor observa.

LA CONSTANTE

Nada se sostiene por sí mismo;

ni la luz,

ni la gravedad,

ni la fuerza que ata el núcleo.

Un error menor que cero

bastaría

para deshacerlo todo.

Y, sin embargo,

permanece.

Un orden sin causa visible,

un pulso que no varía.

El misterio

no es la materia,

sino

quién mantiene

sus constantes.

LAS CUATRO FUERZAS

Gravedad:

tensión del abismo,

curvatura del ser.

Electromagnetismo:

luz que ordena el movimiento,

vínculo entre lo visible y lo pensado.

Fuerza fuerte:

nudo del núcleo,

la fidelidad de la materia.

Fuerza débil:

paso de lo que muere

a lo que aún puede ser.

Cuatro constantes;

una sola respiración del mundo.

KAIROS

Medimos el tiempo como Kronos:

sucesión, desgaste, medida.

Sin embargo,

Kairos nos acerca al Ser,

a la plenitud que no pasa,

al instante que no transcurre

porque ya es.

CONTACTO

Entre el núcleo

y las partículas de un átomo

media un vacío inmenso.

La materia no es sólida;

nadie se toca.

Solo el amor

hace contacto