Israel Centeno

🇪🇸 Dios y el acto puro:

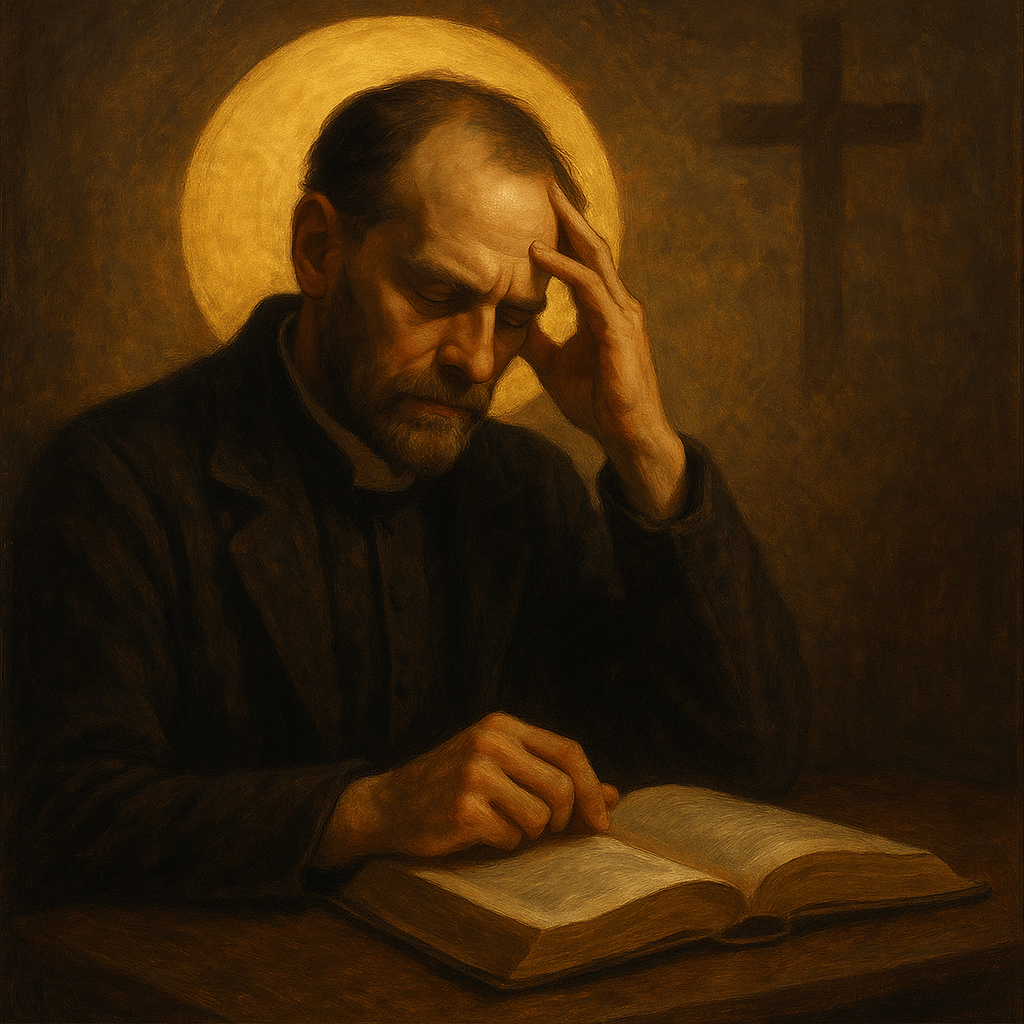

“Solo el alma en silencio puede oír a Dios

Cuando Wittgenstein escribe al final del Tractatus “De lo que no se puede hablar, hay que callar”, no niega lo trascendente; señala su límite. Ese silencio no es vacío: es reverencia. No dice “Dios no existe”, sino “Dios no cabe en el lenguaje”. Lo indecible no desaparece: brilla en el límite de lo que puede decirse.

La fenomenología, al suspender toda valoración y prejuicio mediante la epoché, nos enseña a mirar sin categorías, a dejar que el ser se manifieste tal como es. Si aplicamos ese método a lo divino, descubrimos que el silencio wittgensteiniano no es negación, sino apertura. Callar no es renunciar a la palabra, sino prepararla. La epoché fenomenológica, en su forma más pura, se convierte en un ejercicio espiritual: una purificación del alma que, al abandonar el juicio y la interpretación, abre espacio a lo que se revela por sí mismo.

Así como Wittgenstein lleva el lenguaje a su límite, la fenomenología nos conduce al límite de la conciencia. Lo que el lenguaje no puede decir, la conciencia puede acoger en silencio. Allí donde la palabra termina, comienza la experiencia. Dios no es un objeto entre objetos, ni un fenómeno dentro del horizonte del mundo. No se da como algo de lo que podamos tener “experiencia” en sentido empírico. Pero sí se da como fundamento de todo darse, como fuente del aparecer. No se muestra como figura, sino como aquello que permite que algo aparezca.

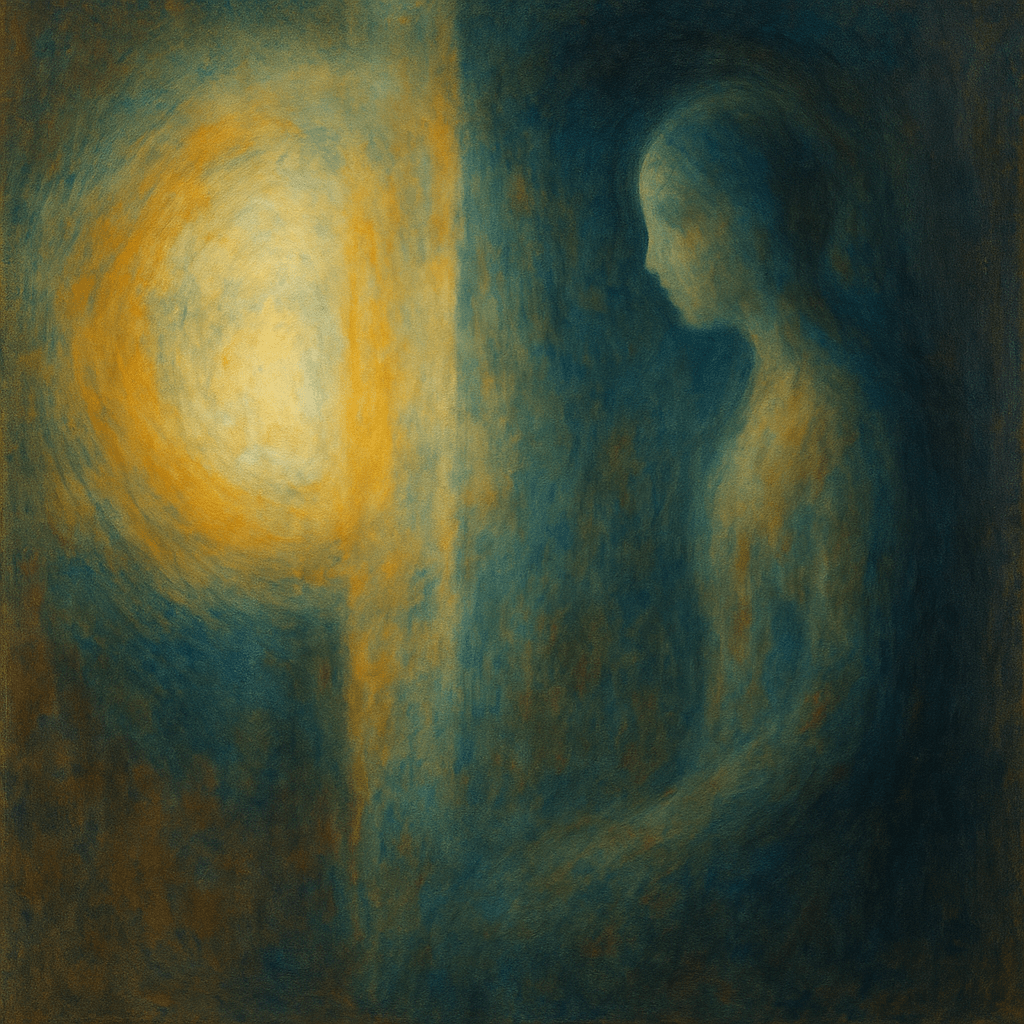

Dios, entonces, no es fenómeno, pero todo fenómeno auténtico remite a Él. El ser finito, al mostrarse, revela su límite, y en ese límite brilla la infinitud. Fenomenológicamente, lo divino no se impone ni se prueba: se deja entrever. La conciencia que se descubre finita advierte que su ser no procede de sí misma. Esa conciencia, al encontrarse con su propia contingencia, toca el acto puro, no como contenido, sino como origen. El alma no ve a Dios: se siente mirada por Él.

El actus purus —el Ser que es solo acto, sin potencia ni cambio— no puede vivirse como experiencia directa. Y sin embargo, es vivenciable en el sentido más alto del término: no como percepción de algo, sino como participación en el ser mismo. Cuando el alma contempla sin juzgar, cuando cesa de constituir el mundo y simplemente acoge lo que se da, experimenta una evidencia silenciosa: la de no ser su propia fuente. En ese instante de claridad, el alma intuye el acto puro como presencia sin forma, como actualidad absoluta que sostiene todo lo que es.

Esa vivencia no ocurre en el discurso racional, sino en la contemplación. Y contemplar, en este contexto, no es pensar ni imaginar: es dejar que el ser se dé sin resistencia. Es el mismo movimiento del alma que describen Teresa de Jesús, San Juan de la Cruz y Edith Stein: cuando el yo se aquieta y el pensamiento se detiene, surge un lugar interior esquivo e infinito, un punto de contacto, un portal donde el alma trasciende el marco espacio-temporal y se abre a lo eterno. Allí no hay sujeto ni objeto, sino comunión. Ese punto, que parece pequeño, es infinitamente vasto, porque en él cabe Dios entero.

En ese espacio interior, Dios se hace semejante a nosotros y nosotros semejantes a Él. Las categorías humanas —sujeto, objeto, pensamiento, tiempo— se disuelven. El alma, liberada de su necesidad de comprender, se entrega. Y en esa entrega, el silencio de Wittgenstein se vuelve el silencio de la contemplación: no el mutismo del límite, sino el recogimiento de la presencia. El callar del filósofo se transforma en el callar del místico.

El acto puro no se “ve”: se reconoce en el ser sostenido. Es lo que hace posible que haya verdad, amor y existencia. La contemplación no es un modo de observar a Dios, sino el modo en que Dios nos deja participar de su propio acto de ser. El silencio final del Tractatus encuentra así su correspondencia en la oración contemplativa: la palabra que ya no nombra, porque se ha convertido en presencia.

Hablar de Dios desde la fenomenología es hablar desde el silencio. No es definir ni demostrar, sino dejar que lo que sostiene todo aparecer se revele en la conciencia abierta. Dios no puede categorizarse ni como sujeto ni como objeto, porque trasciende ambos: es la unidad absoluta donde conocer y ser se identifican. En Él, el acto puro es plenitud, y la contemplación es el modo humano de participar en esa plenitud.

Allí donde el tiempo se suspende, la conciencia deja de preguntar y se vuelve adoración. El alma descansa en la Luz.

A Phenomenological Reading of Silence

🇬🇧 God and the Pure Act:

“Only the soul in silence can hear God.” — Edith Stein

When Wittgenstein writes at the end of the Tractatus, “What we cannot speak about, we must pass over in silence,” he does not deny the transcendent; he marks its limit. That silence is not emptiness—it is reverence. He does not say “God does not exist,” but “God cannot fit within language.” The unsayable does not vanish; it shines at the boundary of what can be said.

Phenomenology, by suspending all valuation and prejudice through the epoché, teaches us to look without categories, to let being reveal itself as it is. Applied to the divine, this means that Wittgenstein’s silence is not negation but openness. To be silent is not to renounce speech, but to prepare it. The pure epoché becomes a spiritual exercise, a purification of the soul that, by abandoning judgment and interpretation, opens space for what reveals itself.

As Wittgenstein brings language to its boundary, phenomenology brings consciousness to its own. What cannot be said may still be received in silence. Where words end, experience begins. God is not an object among objects, nor a phenomenon within the horizon of the world. He does not “appear” as something of which we can have empirical experience. Yet He gives Himself as the foundation of all givenness, as the source of appearance itself. He is not a figure within the field of vision, but that which allows vision to occur.

God, then, is not a phenomenon, yet every authentic phenomenon points toward Him. Finite being, in showing itself, reveals its limit—and in that limit, infinity glimmers. Phenomenologically speaking, the divine is not imposed or proven; it lets itself be intuited. Consciousness, upon discovering its finitude, perceives that its being is not self-originating. In that discovery lies the first contact with the pure act—not as content, but as source. The soul does not see God; it feels itself seen.

The actus purus—the Being that is pure act, without potentiality or change—cannot be experienced directly. Yet it can be lived, not as perception of something, but as participation in Being itself. When the soul contemplates without judgment, when it ceases to constitute the world and simply receives what is given, it experiences a silent evidence: that it is not its own source. In that clarity, the soul intuits the pure act as formless presence, as the absolute actuality sustaining all that is.

Such experience does not occur in rational discourse but in contemplation. To contemplate here is not to think or imagine; it is to let being give itself without resistance. It is the movement described by Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, and Edith Stein: when the self grows still and thought ceases, there emerges an inner space—elusive, infinite—a point of contact, a portal through which the soul transcends the frame of space and time and opens to the eternal. There is no subject or object there, only communion. That point, which seems so small, is infinitely vast, for it contains the fullness of God.

In that interior space, God becomes like us, and we become like God. Human categories—subject, object, thought, time—dissolve. The soul, freed from its need to understand, yields. And in that yielding, Wittgenstein’s silence becomes the silence of contemplation: not the muteness of limit, but the stillness of presence. The philosopher’s silence becomes the mystic’s silence.

The pure act cannot be “seen”; it can only be recognized in the being sustained. It is what makes truth, love, and existence possible. Contemplation is not a way of observing God, but the way God allows us to share in His own act of being. The final silence of the Tractatus thus finds its correspondence in contemplative prayer: a word that no longer names, because it has become presence.

To speak of God phenomenologically is to speak from silence—not to define or prove, but to let what sustains all appearance reveal itself in open consciousness. God cannot be categorized as subject or object, for He transcends both: He is the absolute unity where knowing and being are one. In Him, pure act is fullness, and contemplation is our way of participating in that fullness.

Where time is suspended, consciousness ceases to question and becomes adoration. The soul rests in the Light.