VOLVER AL DIOS QUE LLAMA POR NUESTRO NOMBRE

Israel Centeno

El primer mandamiento no llegó como una prohibición fría, sino como una brújula para el corazón:

“Escucha, Israel: el Señor es nuestro Dios, el Señor es Uno.”

Esa afirmación, antes que norma, es identidad. Es la voz que nos recuerda quiénes somos y hacia dónde gira la vida. Y, sin embargo, desde que esa voz resonó, el ser humano ha tenido la tendencia constante a fabricar ídolos, aun cuando se cree demasiado lúcido, demasiado moderno o demasiado iconoclasta como para caer en ellos.

La verdad es más simple y más dolorosa: no sabemos vivir sin adorar algo.

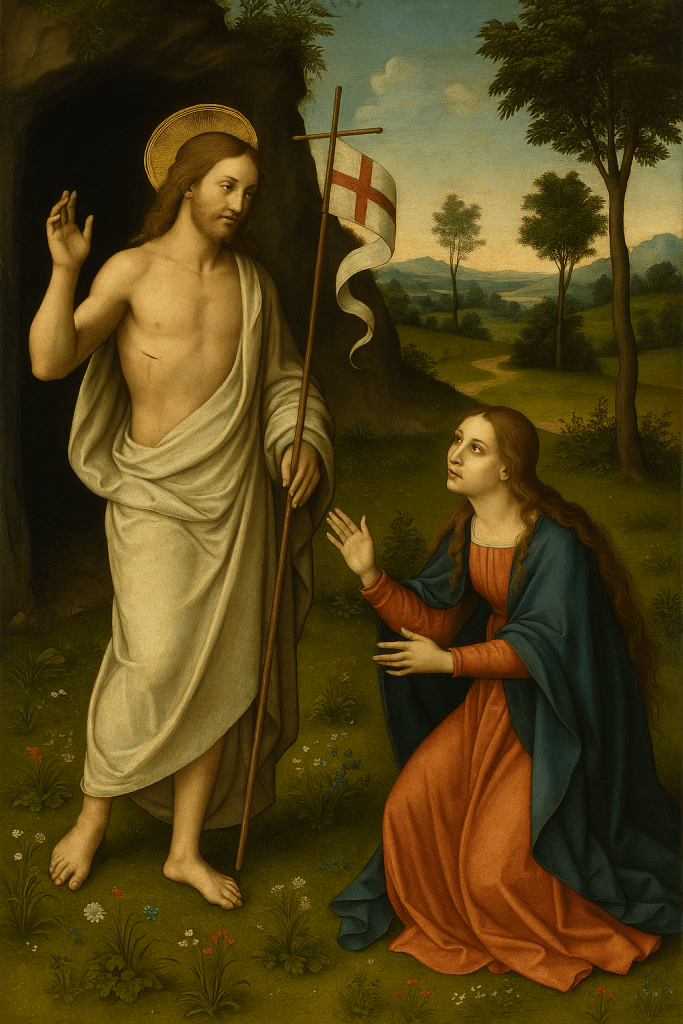

El episodio del becerro de oro lo revela con exactitud. Moisés sube al encuentro de Dios y el pueblo, sintiéndose huérfano, se desespera. No soporta la espera, no tolera el silencio de la montaña. Entonces hace lo que hace el corazón humano cuando pierde el centro: construye un dios visible. No por rebeldía, sino por miedo. No por paganismo, sino por vulnerabilidad. No por maldad, sino por abandono.

El becerro de oro es un espejo.

No muestra un pueblo primitivo, sino la anatomía espiritual del hombre: cuando la fe se debilita, la reemplaza; cuando Dios calla, inventa un sustituto; cuando no ve, fabrica una imagen; cuando no siente, se arrodilla ante lo que brilla.

La idolatría no desaparece, solo cambia de forma.

Después vendrán los cuarenta años de desierto, ese largo trabajo de purificación. No fue un castigo, sino una escuela: aprender a vivir sin depender de lo que se toca, se ve o se manipula. Aprender a confiar en el Dios que habla desde el silencio y alimenta desde la nada. Era necesario vaciarse para poder reconocerlo cuando, en la plenitud del tiempo, se hiciera carne y habitara entre nosotros.

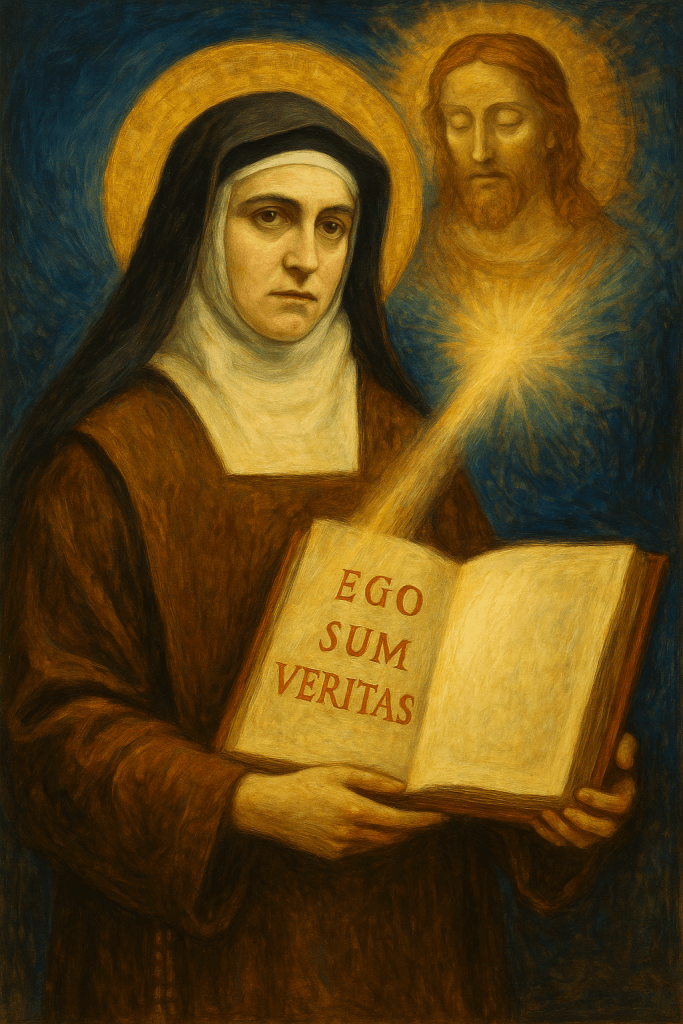

La Encarnación es la gran ruptura: el Dios único se acerca, se deja ver, se deja tocar. Y, sin embargo, al revelarse como Hijo, nos introduce en el misterio más alto: la unidad eterna del Padre, del Hijo y del Espíritu, esa comunión viva que Ireneo descifra y que el Concilio de Nicea proclama para siempre.

Un solo Dios, tres personas:

la unidad más perfecta, el amor más perfecto, la libertad más perfecta.

Pero mientras el cielo se abría, la tierra seguía —y sigue— levantando ídolos.

El laicismo moderno, creyéndose liberado de la religión, inauguró otro tipo de paganismo: dinero, éxito, cuerpo, prestigio, poder, autoimagen, productividad, consumo. Y ahora, en un giro nuevo, la fascinación por lo tecnológico: máquinas, pantallas, algoritmos, inteligencias artificiales. La criatura se inclina ante lo que fabrica, como si buscara en su obra una trascendencia que solo el Creador puede dar.

No hace falta creer en dioses antiguos para vivir de rodillas:

basta con entregarle el corazón a lo que no puede sostenerlo.

La idolatría es psicológica antes que teológica: nace de un miedo.

Miedo a la soledad, a la falta de valor, al fracaso, al abandono.

Ningún ídolo existe sin una herida que lo sostiene.

Por eso no se destruyen con golpes; se desmontan con verdad.

El primer paso es reconocer la herida.

El segundo, distinguir qué acompaña y qué esclaviza.

El tercero, aprender a esperar sin fabricar dioses de emergencia.

El cuarto, abrirse a la presencia que no siempre se siente, pero siempre sostiene.

Desmontar un ídolo es dejar que Cristo ocupe el espacio que le pertenece.

No para imponer, sino para liberar.

No para exigir, sino para sanar.

No para suplantar la humanidad, sino para llenarla de luz.

La cultura actual nos empuja hacia la saturación: demasiados estímulos, demasiadas voces, demasiadas imágenes. Y sin embargo, en esa saturación, el alma siente más que nunca la sequedad. Somos un pueblo que camina por un desierto lleno de espejismos. Desde afuera parece abundancia; desde adentro es sed.

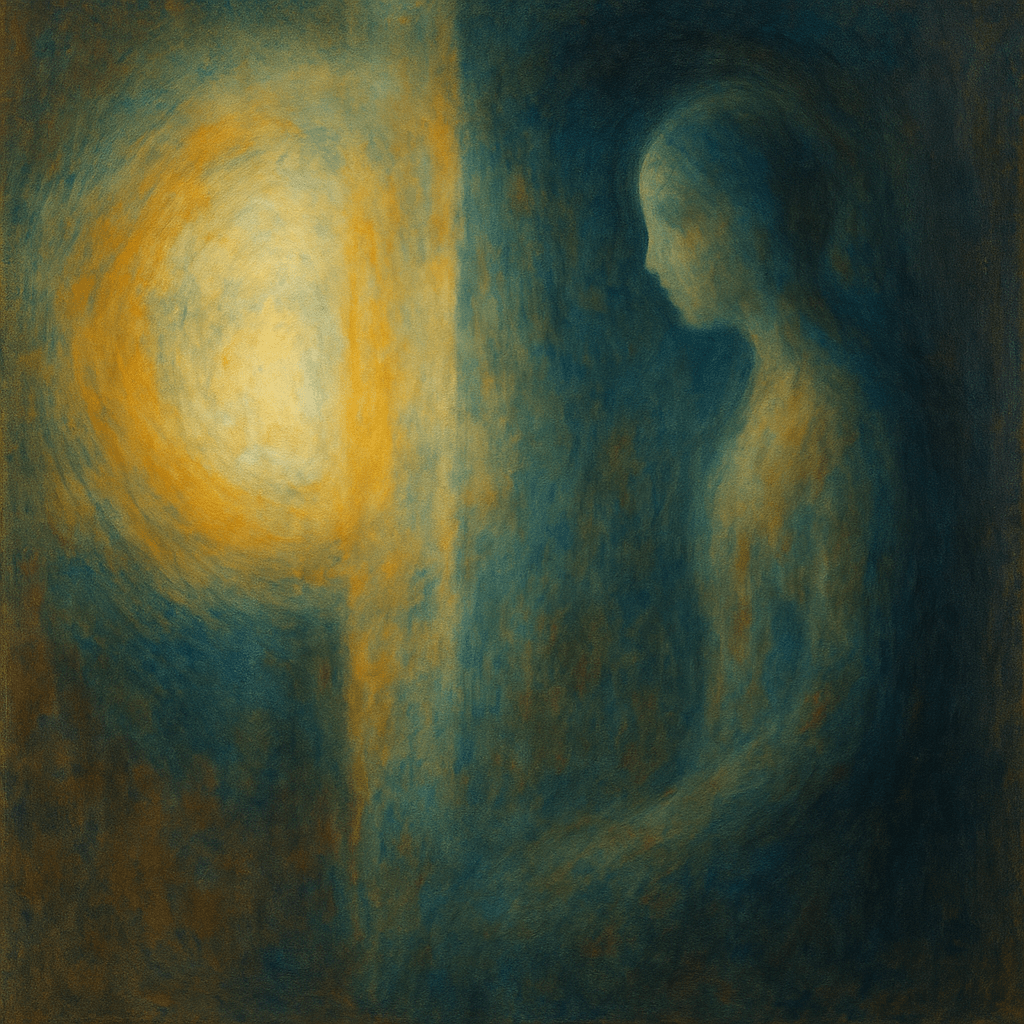

Pero el desierto no es un castigo.

Es el lugar donde vuelve a resonar la palabra esencial:

“Yo soy.”

Volver al Dios único y trinitario es regresar al centro del alma, donde ninguna imagen puede ocupar su lugar. Es respirar sin miedo en un mundo que pide adoración constante. Es redescubrir la libertad de quien ya no necesita idolatrar nada, porque sabe que es amado desde dentro. Es contemplar el mundo sin arrodillarse ante él.

Cuando las imágenes caen, queda la Presencia.

Cuando los ídolos se desvanecen, aparece la verdad.

Cuando el corazón vuelve al único Dios, vuelve también a sí mismo.

Y así, una vez más, el mandamiento se vuelve llamada, no imposición:

“Escucha, Israel… el Señor es Uno.”

Ese Uno es amor, y ese amor es la única adoración que libera.

🇬🇧 IDOLATRY

RETURNING TO THE GOD WHO CALLS US BY NAME

The first commandment did not descend as a cold prohibition but as a compass for the heart:

“Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One.”

Before it was law, it was identity —a voice reminding us who we are and where life turns. And yet, from the moment that voice sounded, humanity has carried the constant temptation to build idols, even when we consider ourselves too modern, too rational, too iconoclastic to fall into such things.

But the truth is simpler and more painful: we do not know how to live without worshipping something.

The story of the golden calf reveals this with unsettling clarity. Moses climbs the mountain to meet God, and the people below, feeling abandoned, grow anxious. They cannot bear the waiting. They cannot tolerate the silence. And so they do what the human heart always does when it loses its center: they make a visible god. Not out of malice, but out of fear. Not out of rebellion, but out of desperation.

The golden calf is a mirror.

It does not show a primitive people; it shows the structure of the human soul.

When faith weakens, we replace it.

When God is silent, we invent substitutes.

When we cannot see, we fabricate an image.

When we cannot feel, we bow to whatever shines.

Idolatry never disappears; it simply adapts.

Then come forty years in the desert, a long purification. It was not punishment but formation: learning to live without clinging to what can be touched, seen, or controlled. Learning to trust the God who feeds from nothing and speaks from silence.

And in the fullness of time, something greater happens: God becomes flesh.

With Christ, the One draws near, becomes visible, becomes touchable, and reveals that the eternal unity proclaimed in the Shema contains a mystery deeper than we imagined: the communion of Father, Son, and Spirit. Irenaeus discerns it; Nicea proclaims it.

But while heaven opened, the earth kept producing idols.

Modern secularism, believing itself free of religion, ended up creating a new paganism: money, success, the body, prestige, power, productivity, consumption. And now, a new fascination arises: technology as a kind of human-made transcendence. Artificial intelligence as a mirror of human desire for omnipotence. Prometheus with a touchscreen.

One does not need ancient gods to kneel.

One only needs to give the heart to something that cannot hold it.

Idolatry is psychological before it is theological.

It is born from fear —fear of loneliness, of failure, of insignificance, of abandonment.

Every idol stands on a wound.

Thus, idols are not smashed from the outside; they are dissolved from the inside.

The first step is to recognize the wound.

The second, to discern what accompanies and what enslaves.

The third, to learn to wait without fabricating emergency gods.

The fourth, to open oneself to a Presence that does not always feel close but never ceases to sustain.

Dismantling an idol is allowing Christ to inhabit the place that has always been His.

Not to impose, but to free.

Not to demand, but to heal.

Not to shrink humanity, but to fill it with light.

Our culture saturates us with images, voices, distractions. And yet, in the middle of that saturation, the soul feels a deeper dryness than ever. We are a people wandering a desert full of mirages. From the outside it looks like abundance; from within, it is thirst.

But the desert is not a punishment.

It is the place where the essential word sounds again:

“I AM.”

To return to the one and triune God is to return to the center of the soul, where no image can take His place. It is breathing freely in a world that constantly demands devotion. It is rediscovering the freedom of a heart that no longer needs idols because it knows it is loved from within. It is learning to look at the world without bowing before it.

When images fall, Presence remains.

When idols vanish, truth appears.

When the heart returns to the One, it returns to itself.

And so the commandment becomes invitation, not imposition:

“Hear, O Israel… the Lord is One.”

That One is love, and that love is the only worship that liberates.